Art & Tech

How Neri Oxman’s New Lab Is Fusing Biology and Tech to Design a Sustainable Future

Her new lab and design studio, Oxman, is crafting products and environments to serve both clients and the natural world.

Her new lab and design studio, Oxman, is crafting products and environments to serve both clients and the natural world.

Min Chen

What if every object we use was designed to work with the environment, not against it? That’s a line of inquiry that Israeli American designer and inventor Neri Oxman has pursued for some 20 years in work that has mined the nexus of biology, engineering, and design.

Her approach, which she dubbed Material Ecology, weds the human-built and the nature-grown in the name of environmental sustainability. With her Mediated Matter research group at M.I.T., she’s paired live silkworms with robotics, biomaterials with 3D printing, melanin with architecture—her work featuring in art museums as much as scientific literature. Björk has come calling, as has Iris van Herpen.

Now, Oxman is poised to introduce her designs on a larger scale, for wider application. “Following almost two decades in academia,” she told me over email, “I am eager to get ‘into the wild.'”

A grow room at Oxman, capable of simulating any period in Earth’s history. Photo: Nicholas Calcott, courtesy of OXMAN.

Her new endeavor, Oxman, a designer studio and lab launched last month in a 36,000 square-foot, two-story space in New York, housing a robotics shop, workshop, architectural studio, wet lab, among other research facilities. Here, Oxman and her team will ideate and create products and environments to serve both clients and the natural world.

It’s urgent work as the climate crisis envelops our planet, nature is despoiled, and avid consumption generates ever-more non-biodegradable waste. The lab’s response follows from Material Ecology, with designs targeting molecular, product and architectural scales to generate positive ecological impacts. In short, it’s seeking to reinvent everyday objects—from our food to our clothes to our homes—such that their lifecycles benefit ecosystems and environmental restoration.

Inside Oxman. Photos: Nicholas Calcott, courtesy of Oxman.

“This new way of design and designing aims to replenish—rather than exploit—the natural world,” said Oxman. “In a world where human-made materials are biocompatible, designed products are indistinguishable from naturally grown produce. Using programmable decomposition, materials can rejoin the ecosystem and fuel new growth.”

Case in point: the lab’s Oo platform, which approaches the design and fabrication of products with an eye toward natural growth and decomposition. At its heart are polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), a class of biodegradable material generated by bacteria fed on natural resources. The lab has deployed its 3D-printing robots to create textiles, based on and blended with PHAs, that can ultimately be re-consumed by bacteria. It’s a zero-waste process that Oxman characterized as “100 percent PHA, 100 percent biodegradable, zero percent microplastics, infinite life.”

A wall of shoe prototypes designed at the Oxman over the course of a year. Credit: Nicholas Calcott, courtesy of Oxman.

With its Oo knitting technology, the lab has unveiled a collection of shoes crafted entirely with PHAs. Where their outer skins boast a knitted texture that offers cushioning and reinforcement, their insides hold a knitted sock designed with human motion in mind. The shoes are further shaped during fabrication, thus eliminating the need for assembly.

“No assemblies, no glues,” Oxman added of the footwear. “In place of assembling discrete parts, each with their own inert material and homogeneous properties, we created biocompatible mono-materials characterized by highly tunable property gradients and multi-functionality.”

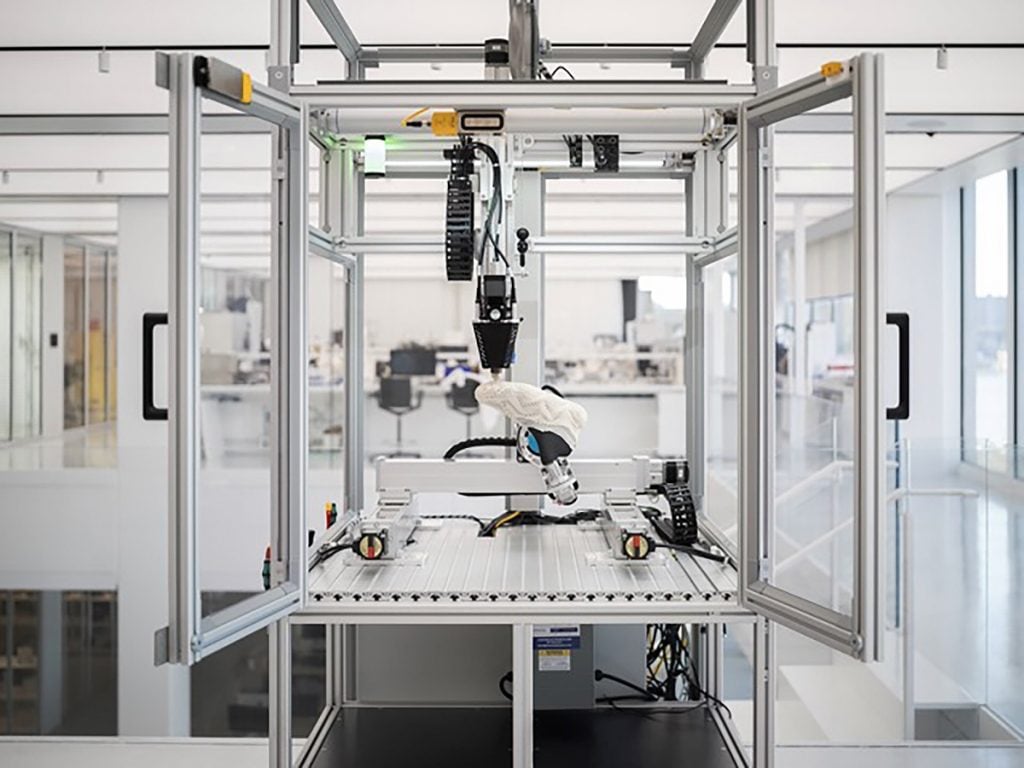

A fully automated, custom 5-axis robotic 3D printer enables end-to-end digital fabrication of bio-based consumer goods, displacing the traditional assembly line. Photo: Nicholas Calcott, courtesy of Oxman.

The lab is working on a massive scale, too. Its Eden project takes an ecological approach to masterminding urban environments. Using “rapid environmental simulation” software, Eden identifies how architectural designs can deliver the most ecological good, encompassing factors such as habitat connectivity, ecosystem stability, and resource availability.

Oxman and her team has already established a partnership with Australian property firm Goodman Group to explore new building methodologies that can enhance the ecological productivity of the built environment. This work, said Oxman, includes the goals of “sequestering dozens of kilotons of carbon per year, providing habitats for endangered species,” while working toward replenishing and rewilding local ecosystems—a model she hopes will offer a roadmap for future building projects.

Computationally “grown” and ecologically programmed, the Eden Tower’s spatial and species distributions prioritize a site’s biodiversity, resilience, and ecosystem services, aiming for positive environmental occupancy impacts. Photo: VA-Arts, courtesy of Oxman.

The lab is also studying ecologies at a granular level, exploring how molecular design can heal ecosystems and advance polycultures to reverse the harms of monocropping. For a project titled Alef, it has built four data-driven grow rooms that can be programmed with various environmental parameters—temperature, light, airflow—to address specific ecological challenges. Ancient and even extinct ecosystems might be given a second chance. The New York Botanical Garden is already on board.

The nature of this discipline-straddling work naturally calls for collaboration, which Oxman is no stranger to. Where her Mediated Matter initiative saw her join forces with M.I.T. students, her new physical lab has been built to accommodate some 133 scientists, engineers, and designers. She speaks of this teamwork as a dance, bringing up Gaga, a movement language she picked up from Israeli choreographer Ohad Naharin.

“In Gaga, there are no right or wrong ways to move. I often share with my team that good design is more about ‘usefulness’ and ‘uselessness’ than it is about ‘rightness’ and ‘wrongness’ when your values are solid,” she explained. “Gaga is also a dance language that avoids mirrors… Similarly, great innovation is not about mirroring what exists. It is about fusing technical skills with deep intuition to enable and inspire discovery.”

Left: Oxman team members take part in a Gaga dance workshop in the Atrium. Right: Oxman’s Wet Lab located above the studio. Photos: Nicholas Calcott, courtesy of Oxman.

This dance is similarly invoked in Oxman’s own vision, where the made and the grown, biology and technology, the material and ecological interface and ultimately converge. She has high hopes for the future it is crafting. Her new lab may have sprouted from a conceptual framework developed over decades, but in ways, its work has just begun.

“Our long-term hope is to make a real and meaningful impact through design,” said Oxman. “More than anything, I long for meaningful interactions between living and non-living beings. I long for the day perfumes can interact with trees, shoes can transform into edible berries, and data centers can rewild a struggling ecosystem.”