People

How Barbara and Aaron Levine Became Two of America’s Most Committed Collectors of Conceptual Art

The Washington, D.C.-based couple, who just donated a trove of works by Marcel Duchamp to the Hirshhorn, trace their evolution as collectors.

The Washington, D.C.-based couple, who just donated a trove of works by Marcel Duchamp to the Hirshhorn, trace their evolution as collectors.

Menachem Wecker

![]()

Trying to keep up with octogenarian collectors Aaron and Barbara Levine’s banter is like playing third wheel to Frank and Marie Barone of Everybody Loves Raymond. We’ve barely sat down in their sitting room in the Kalorama neighborhood of Washington, D.C.—a Rirkrit Tiravanija shrimp pad thai sculpture between us—when they begin finishing each other’s sentences, correcting each other’s memories, and tempering each other’s polemics.

Reflecting on his long-standing obsession with Marcel Duchamp’s genius, Aaron says he couldn’t rank the pioneering conceptual artist any higher: It’s “him and Jesus Christ,” he says. “Don’t say that,” Barbara cuts in, laughing. Aaron amends: “Him and Freud.”

Over the past 30 years, Barbara and Aaron Levine—a former Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden trustee and a retired lawyer—have assembled one of the most extensive holdings of Duchamp’s work in private hands, alongside an eclectic trove of work by other artists ranging from Sol LeWitt to Lorna Simpson. Although they have spent decades loaning works to museums and steadily growing their holdings, they kept a relatively low profile until September, when they announced plans to donate some 35 works by Duchamp to DC’s Hirshhorn.

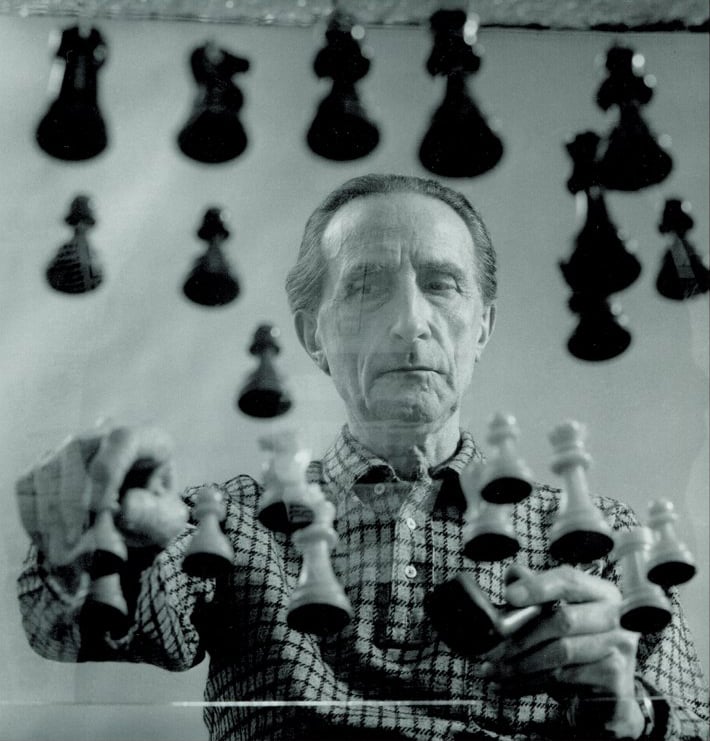

Arnold Rosenberg, Marcel Duchamp playing chess on a sheet of Glass (1958). Promised gift of Barbara and Aaron Levine to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC.

It’s a trove many museums coveted. “This is the art world equivalent of the Wizards getting LeBron James,” Hirshhorn board chairman Daniel Sallick told the Washington Post at the time.

The couple’s tastes often diverge, with Barbara drawn to Minimalism and Aaron laser-focused on even more cerebral conceptual art. The works in their home, hung cheek by jowl down the halls, are the result of constant, lively exchange and debate between them.

But whatever you do, don’t call it a collection. Aaron asks that the word be avoided in describing the art he and his wife have assembled, because it makes artworks sound like a “thing.” Unlike collectors who only buy work that conforms to specific criteria—a specific date range, for example, or a particular medium—Barbara explains that “we are all over the place.” In lieu of “collection,” Aaron prefers the term “melange.”

Aaron and Barbara Levine’s home in Washington, DC. Photo: Menachem Wecker.

While many successful attorneys opt to take up golf, Aaron and Barbara’s aesthetic pastime swaps one kind of weighty intellectual pursuit for another. “Artists are about as far away from lawyers as you can get,” he says. When he was once asked to give a talk about how art changes the law, he got up and said, “It doesn’t. Goodbye.” (Aaron also has another hobby—glassmaking—though he calls it “trash” and stores the glassworks in the garage.)

In the couple’s sitting room, there is no shortage of artists dealing with weighty subjects. Two crouched figures by Thomas Schütte and Juan Muñoz guard either side of the doorway. Above, a work by conceptual pioneer Lawrence Weiner states: “Built to see over the edge.” Works by Larry Bell, Isa Genzken, Ernesto Neto, Claes Oldenburg, Yutaka Sone, and Franz West are installed nearby.

This art couldn’t be further from what the Levines, growing up, would have expected to adorn their future home. And their aesthetic has taken a sharp turn from when they started collecting.

Aaron and Barbara started dating in high school and married soon after she graduated Skidmore College. He was in law school at George Washington University, which brought them to the District; they never left. They’d grown up living on the same floor of the same Brooklyn apartment building. “Can you imagine anything so boring?” Aaron says. Their fathers—hers an optometrist, his a pharmacist—had shops on the same street. When Barbara invited Aaron to her sweet 16 party, his mother wouldn’t let him go. But they found each other anyway.

The two aren’t keen to go down memory lane to discuss the origins of their not-a-collection. Neither grew up going to museums or with much art around the house. Lithuanian-born, American social realist artist Ben Shahn and Barbara’s father were cousins, but they weren’t close. “So you got the genes,” Aaron says. They both laugh.

Aaron and Barbara Levine’s home in Washington, DC. Photo: Menachem Wecker.

“We never thought about collecting,” Barbara adds. “We still don’t,” Aaron chimes in. Barbara continues, “It’s not what we do. We buy things we like that excite us, but never, ‘Oh I’ve got to buy this for the collection.”

They started with posters and “kind of boring stuff,” Barbara says. So what was the first piece they bought as a couple? “Who knows?” Barbara says. Aaron suspects it was a Joel Shapiro. Barbara is sure it wasn’t. “We bought posters,” she says. “It was nothing. Posters and pretty things.”

Around 30 years ago, the Levines decided to get more serious about art collecting. Then living in Bethesda, Maryland, they bought an Andy Warhol series of “10 Jews” from the Jewish Community Center.

When Aaron began traveling back and forth to Holland on business, Neal Benezra, a former Hirshhorn curator and now director of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, advised him to check out Europe’s great institutions. “He destroyed us,” Barbara says. “He put me into bankruptcy,” Aaron jokes. (An SFMOMA publicist declined comment.)

Aaron and Barbara rode the train—something they no longer do after they were hospitalized following a May 2015 Amtrak crash, which was nearly fatal for Aaron—from town to town in Germany and saw works by Otto Dix, George Grosz, and Max Beckmann. “He was addicted to German expressionism and social realism,” Barbara says of her husband.

Barbara, meanwhile, was drawn to Minimalism. “I could look at a white painting and cry, not knowing anything about it,” she says. “We are at totally opposite ends of the spectrum.”

Aaron and Barbara Levine’s home in Washington, DC. Photo: Menachem Wecker.

But then, the two flipped. Aaron started falling for conceptual art—“Duchamp and his children”—and about 20 years ago, they bought their first Duchamp.

Many of the works on display in their home during our interview had recently come out of storage. Sixty works by Kosuth, Kawara, and others—as well as typewriters and 130 books from their extensive library—were on loan to the Art Institute of Chicago for the exhibition “Out of the Retina, Into the Brain: The Art Library of Aaron and Barbara Levine” (through March 2019). The books represent a small slice of their 8,000-volume library, which are stuffed into shelves in the sitting room where we talk. They have pledged to leave the entire thing to the Art Institute.

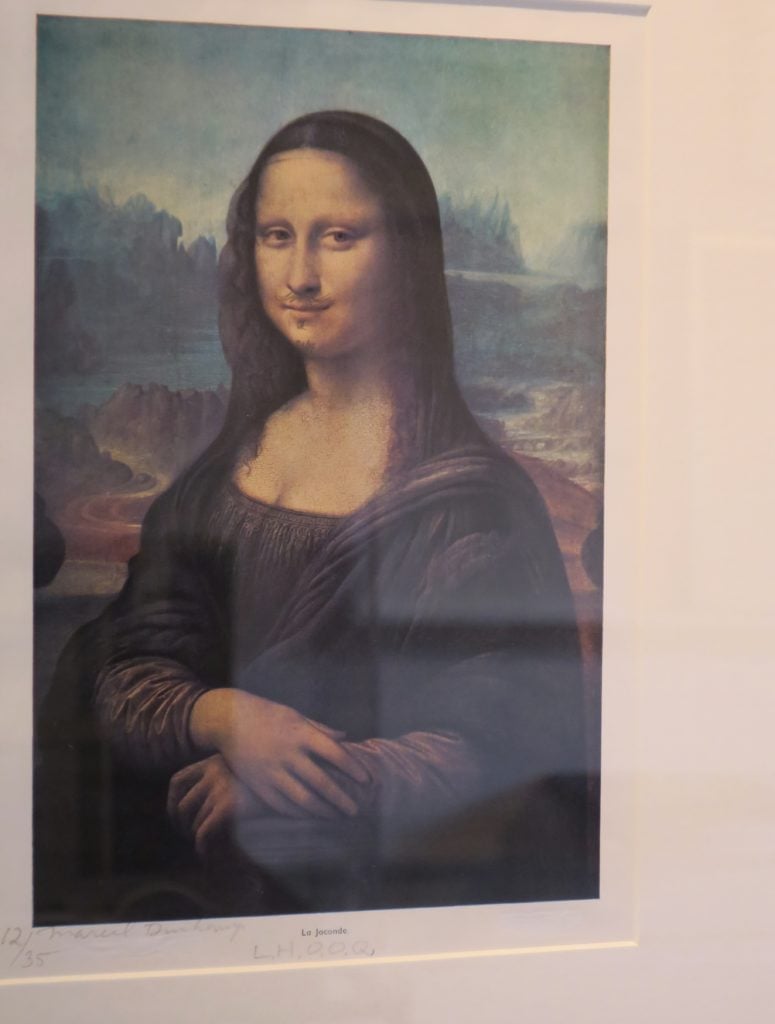

Marcel Duchamp, The Box in a Valise/Boite en Valise (Series E) From or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy [de ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy] (1963). ©Association Marcel Duchamp/ ADAGP, Paris/ Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York 2018.

Aaron says he prefers having the art hanging at home, but gifting the Duchamp trove to the Hirshhorn will mean many children will get to see it in a public, free collection. “Some of them are going to read about it and get the bug,” he says. Barbara leaves open the possibility of splitting up the couple’s non-Duchamp works for future donation.

Since Duchamp overtook pretty posters, the Levines have amassed a large “non-collection” now on view throughout their home, bench players subbing for the A team in Chicago. When they sent the works to the ICA, “we had to rehang the whole house,” Barbara says. “You can’t stand looking at that blank wall.”

Aaron and Barbara Levine’s home in Washington, DC. Photo: Menachem Wecker.

We look at works by Carl Andre, Alexander Archipenko, Joseph Beuys, John Baldessari, Henri Chopin, Tony Cragg, Ralston Crawford, Richard Deacon, Jim Drain, Philip Evergood, Barry Flanagan, Philip Guston, Rebecca Horn, Donald Judd, On Kawara, Anish Kapoor, Stanislav Kolíbal, Joseph Kosuth, Sherrie Levine (no relation), Sol LeWitt, Bruce Nauman, Anne and Patrick Poirier, Sigmar Polke, Marc Quinn, Man Ray, Joel Shapiro, Lorna Simpson, Mark di Suvero, Armando Andrade Tudela, and Andy Warhol. And that’s just on the ground floor and outside.

Duchamp, however, is the clear fan favorite. “Duchamp’s influence is stronger than ever, even if his market remains thin due to his limited output. The concept has come to dominate the aesthetic image in contemporary art, which is very Duchampian,” says Evan Beard, national art services executive at U.S. Trust, Bank of America. “That the Levine’s collection even exists is a testament to dedicated pursuit and an understanding of the artist’s historical importance.”

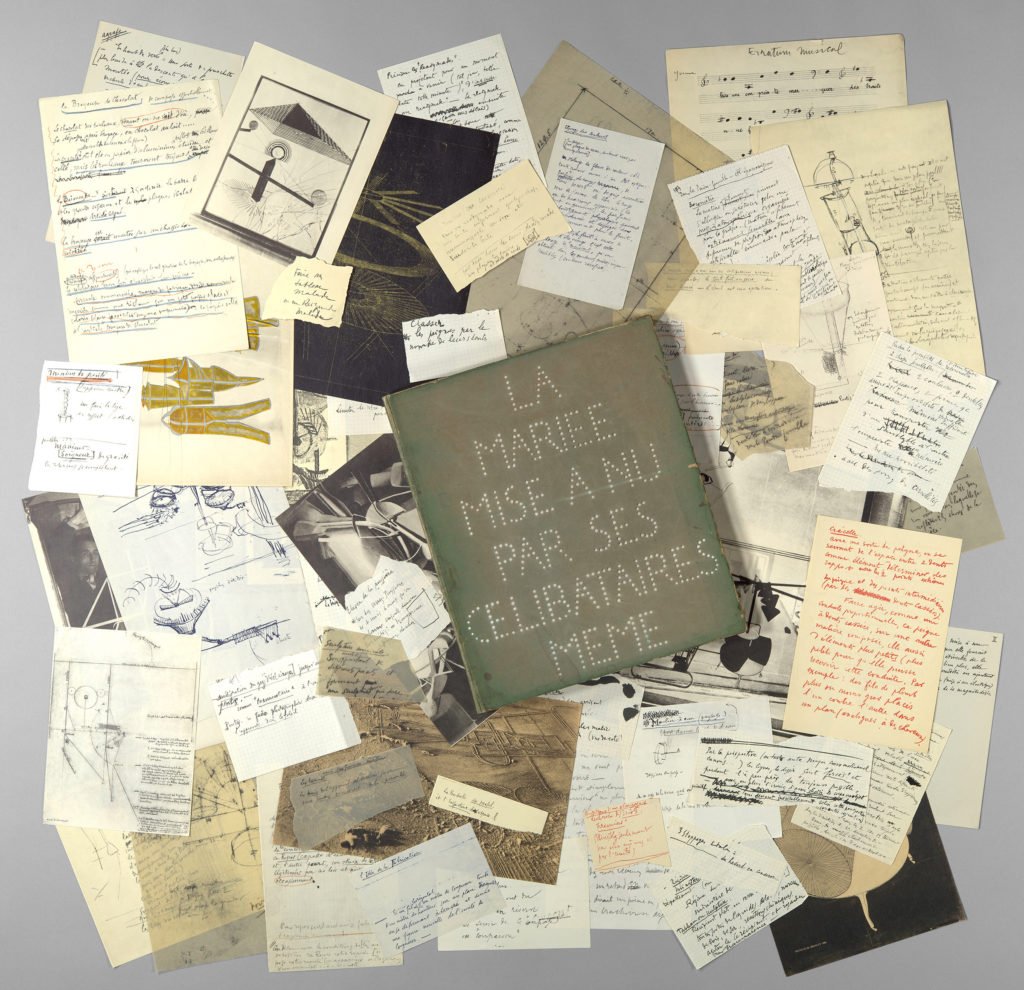

Marcel Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare of Her Bachelors, Even (The Green Box) 1934. © Association Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2018.

That history is something that Aaron and Barbara hope will continue to inspire young Hirshhorn visitors who see their not-a-collection. In 1912, Duchamp went to the Munich industrial fair and saw everything from the X-ray and telephone to the telegraph and steam engine. “The whole world was in an uproar, and he hooked onto that,” Aaron says.

Aaron and Barbara Levine’s home in Washington, DC. Photo: Menachem Wecker.

In Duchamp’s large glass at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Aaron sees a reflection on the “mechanization of sex” in the age of Freud. The arrival of Duchamp announced that “it was a new world.” The art for that new world was mechanical, abstract, and non-representational.

Duchamp’s readymades are a “real kick in the ass” to Aaron, which seems to be among his highest praises. “He’s taking an item: hat rack, doggie comb, bottle rack, urinal, and he’s thrusting it up into the art world. It’s the thrust that’s the art,” he says. “The object is just an ordinary object. So what’s going on? It’s about an idea.”

Aaron and Barbara admit they haven’t always been at the same stop on the aesthetic train at the same time, but “somehow or other we catch up with each other,” Aaron says.

Marcel Duchamp, Porte Chapeau (Hat Rack) 1917/1964. © Association Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2018.

The first time Barbara saw one of On Kawara’s big paintings with a date inscription, her heart stopped. “I was almost in tears,” she says. “He’s looking at me, ‘What are you nuts? What do you like about this?’ But because I liked it so much, he bought it. And you know what? He loves it beyond imagination.”

Barbara responds to art emotionally, while Aaron loves how art inspires him to think and says that you can’t “feel” a Duchamp. When pressed, he admits the boundary between his and her ways of looking at art isn’t so different. “You can’t have emotion without intellect,” he says. “You can’t have intellect without emotion.”

Aaron and Barbara Levine’s home in Washington, DC. Photo: Menachem Wecker.

The thrill they feel puzzling over a Duchamp is increasingly remote for young people drawn ever more to the digital, rather than to physical objects. What’s lost if one collects art made of bits and bytes rather than paint and canvas? “Humanity,” Barbara says. The computer is “too fleeting,” Aaron adds. “Press a button, boom.”