Reviews

Bas Jan Ader at Simon Lee: Why Romantic Conceptualism Is Exactly What We Need Now

Ader's art embraced bravery and assertiveness in the face of absurdity.

Ader's art embraced bravery and assertiveness in the face of absurdity.

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

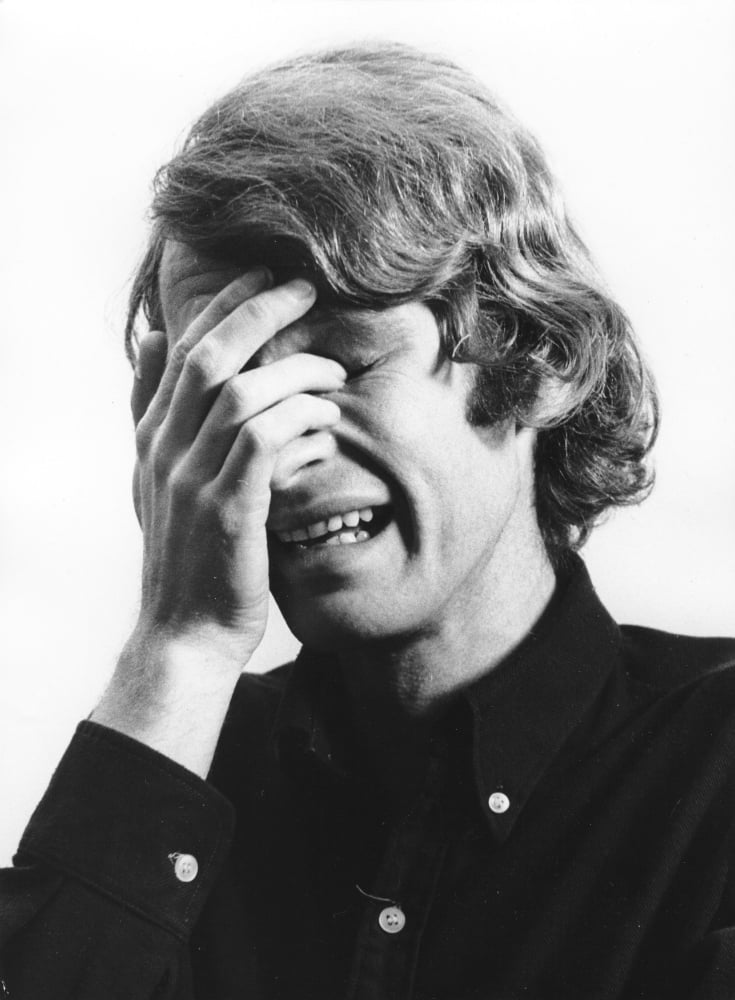

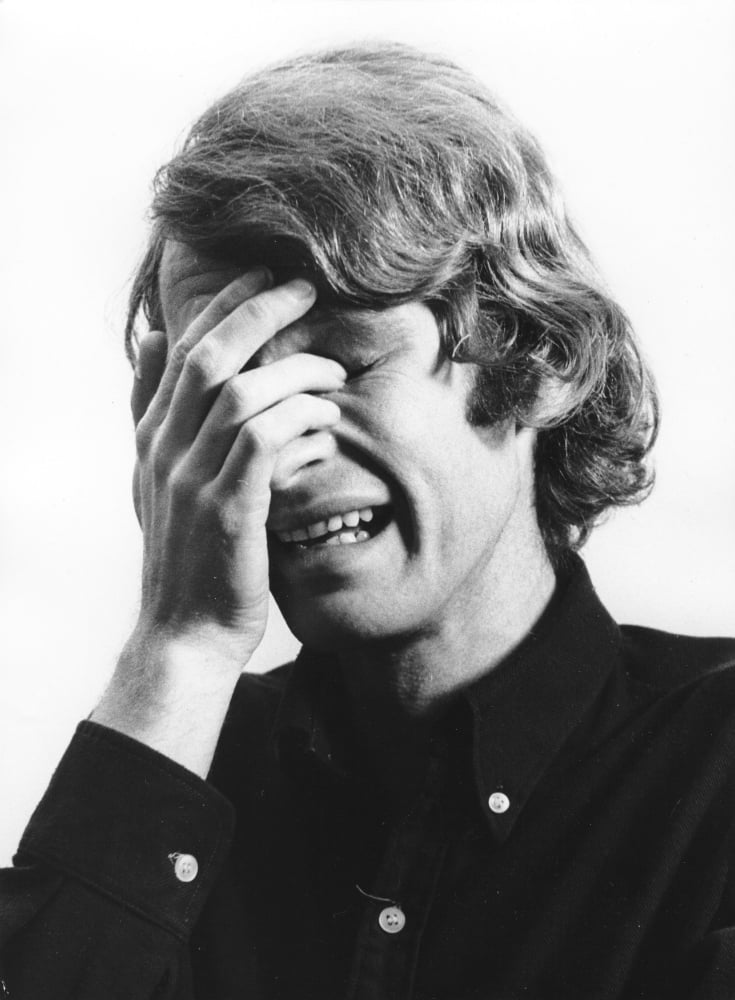

Last Thursday afternoon, as UK citizens braved the torrential rain to vote in a referendum that will probably eject them from the EU, I stood in front of Bas Jan Ader’s most famous film, I’m too sad to tell you (1971), feeling its poignancy and relevance more strongly than ever.

There is something about that piece by Ader that resonates deeply with our current social, economical, and political global landscape: the utter despondency, the lack of words to make sense of all those things that don’t; but also, the need to perform publicly. Nowadays, it seems it isn’t enough to have feelings, one has to emote them openly, via social media mainly, for them to “exist” and be validated.

The film is currently projected—in its original 16mm format—as part of Ader’s solo exhibition at Simon Lee Gallery, which brings together films and a number of related photo works, most of them studies for those films.

Bas Jan Ader, film still from Fall 1, Los Angeles (1970). ©The Estate of Bas Jan Ader / Mary Sue Ader Andersen, 2016 / The Artist Right’s Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Meliksetian / Briggs, Los Angeles and Simon Lee.

Ader’s “falling” films take center stage in the darkened main gallery, starting with Fall 1, in which the artist slips from a chair placed on the roof of his house in Claremont, LA, continuing with the iconic Fall 2, in which he rides his bike into an Amsterdam canal, and culminating with the exquisitely composed and ominous Nightfall, in which he drops a brick on top of two light bulbs, effectively plunging his garage into total darkness.

For obvious reasons, Ader’s oeuvre has been read as tackling the idea of gravity, of falling. For other reasons, to do with his mythical vanishing at sea at the age of 33 during a solitary voyage in the smallest boat to ever attempt to cross the Atlantic—undertaken as part of his project In Search of the Miraculous—it has also been interpreted as dealing with the act of disappearing.

Bas Jan Ader, film still from Nightfall (1971). ©The Estate of Bas Jan Ader / Mary Sue Ader Andersen, 2016 / The Artist Right’s Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Meliksetian / Briggs, Los Angeles and Simon Lee.

And yet, when confronted with the work of the romantic conceptualist par excellence—who was born in Amsterdam but developed most of his short yet influential career in LA—I get the sense of being witness to an artist exhausting the very concept of “attempting” in itself.

Another case in point is Primary Time (1974), a 26-minute video in which Ader rearranges flowers in a vase, grouping them by color. The film is played in an infinite loop at Simon Lee, and also exhibited in the series of photographs Untitled (Flower Work).

For it seems it’s not so much the result—whether success or failure—that matters in Ader’s work. In it, the slapstick fall, the failed sailing trip, the falling tear, become collateral outcomes to the act of trying, which might explain why he chose to perform purposeless tasks, to highlight the very notion of attempting, and persevering.

Bas Jan Ader, film still from Primary Time (1974). ©The Estate of Bas Jan Ader / Mary Sue Ader Andersen, 2016 / The Artist Right’s Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Meliksetian / Briggs, Los Angeles and Simon Lee.

This hunch was confirmed during a symposium at the ICA on Saturday, titled The Legacy of Bas Jan Ader, in which curators Pedro de Llano and Nick Baker, the Turner Prize nominated artist Janice Kerbel, and the critic Jan Verwoert were joined by Ader’s brother Erik and his widow Mary Sue to discuss his work.

When asked what literature Bas Jan was interested in, his brother Erik mentioned two key readings. The first one was Albert Camus’ La Chute (The Fall, 1956), in which the protagonist fails to help a woman who falls into a river and drowns, which in turn plunges him into an existential crisis.

Tellingly, the second, also by Camus, was The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), in which he introduced his philosophy of the absurd by using the famous Greek myth of the king of Ephyra, who was forced to roll a huge boulder up a hill only to watch it roll back down, for eternity.

Bas Jan Ader, On the Road to a new Neo-Plasticism (1971). ©The Estate of Bas Jan Ader / Mary Sue Ader Andersen, 2016 / The Artist Right’s Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Meliksetian / Briggs, Los Angeles and Simon Lee.

While these texts both have the figure of someone or something falling in common, at their core they explore the idea that doing something, no matter how pointless, will always be more rewarding than the haunting regret of having remained passive.

And indeed, Ader took that on board: the 35 pieces that form his body of work were done in a flurry of activity over the span of six years, from 1969 to 1975.

When his widow was asked the obvious question of whether she had tried to prevent Ader from undertaking his final voyage, she said that she never tried to stop him from doing any of his seemingly crazy stunts, like falling from a roof, because she was always completely sure he would manage to see them through.

Their relationship was a process of learning to let him go, she said. “A […] process that has never stopped, even today, and that’s ok,” she added, her voice wavering a little.

Sitting in the dark auditorium in that pregnant moment, it then hit me that maybe that’s precisely the best way to approach Ader’s slippery works: to learn to let them go, so they can briefly be grasped.

“Bas Jan Ader” is now view at Simon Lee Gallery, London, from June 24-August 26, 2016.

Another exhibition of Ader’s work is running concurrently at Metro Pictures, New York.