On View

The Mysterious Art of Belkis Ayón Daringly Sheds Light on One of Cuba’s Secret Societies

Belkis Ayón gets her first, much-deserved museum retrospective.

Belkis Ayón gets her first, much-deserved museum retrospective.

Sarah Cascone

Belkis Ayón took her own life at the age of just 32, cutting short the Cuban artist’s promising career. Yet she left behind a prolific body of innovative prints, mostly in ghostly shades of black and white, which can be seen through this weekend at New York’s El Museo del Barrio.

The exhibition, the artist’s first museum retrospective, travels to Harlem from the Fowler Museum at UCLA. A pioneer of large-scale printmaking featuring often life-size figures—a single work could feature as many as 18 panels—Ayón made her cardboard printing plates with collaged materials including sandpaper, varnish, and abrasives, cutting out elaborate tableaux.

A video in the exhibition shows Ayón running her heavily textured printing surfaces through a hand-cranked printing press, transferring her exquisitely detailed designs to paper.

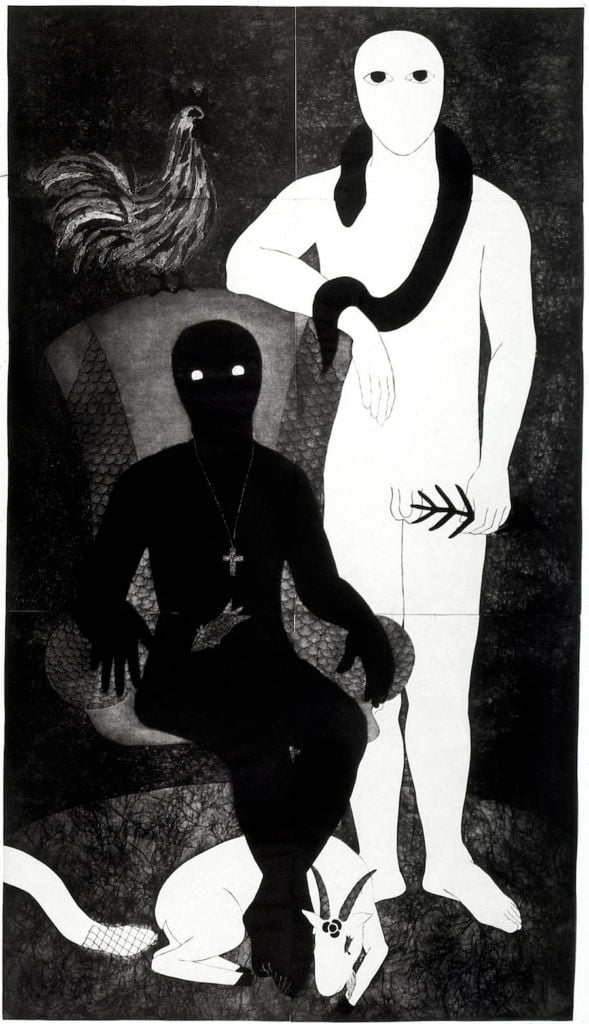

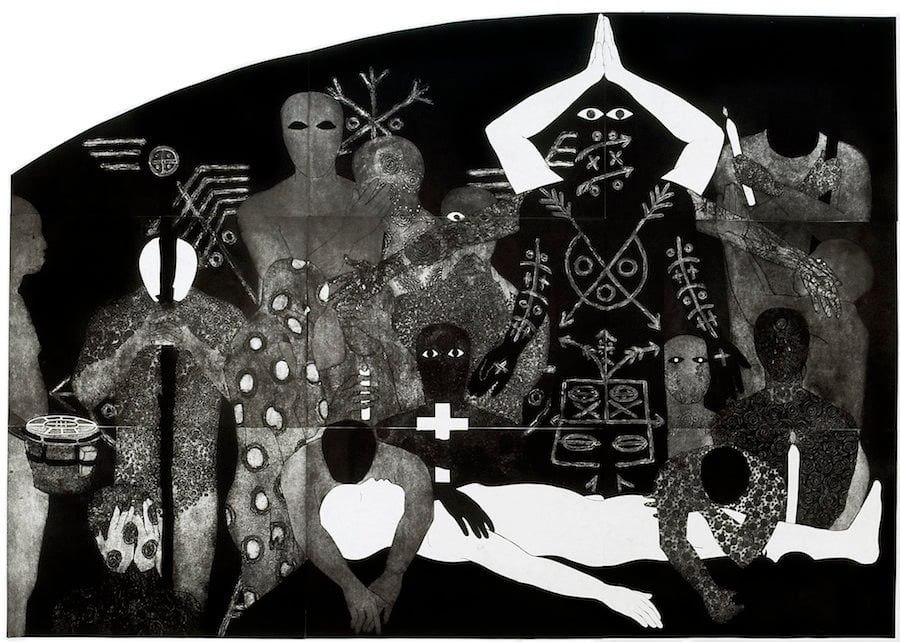

Belkis Ayón, La familia (The Family), 1991 in “NKame: A Retrospective of Cuban Printmaker Belkis Ayón,” at El Museo del Barrio. Collection of the Belkis Ayón Estate.

The artist embraced the unconventional technique, known as collagraphy, out of necessity in the 1990s, with more typical art materials in short supply in impoverished Cuba following the fall of the Soviet Union. When she was invited to show at the Venice Biennale in 1993, Ayón and her father both had to bike 20 miles to the airport, with her artwork, in order to make the journey overseas.

Deeply rooted in her Cuban identity, Ayón’s work was largely inspired by the Abakuá, an all-male Cuban secret society with African roots. Legend has it, however, that the Princess Sikán was the first to hear the voice of Abakuá, whose mystical knowledge was only to be shared with men. She was put to death when the community learned she had broken this sacred rule. But Sikán is alive and well in Ayón’s art, an alter ego for the artist, placed in a position of power.

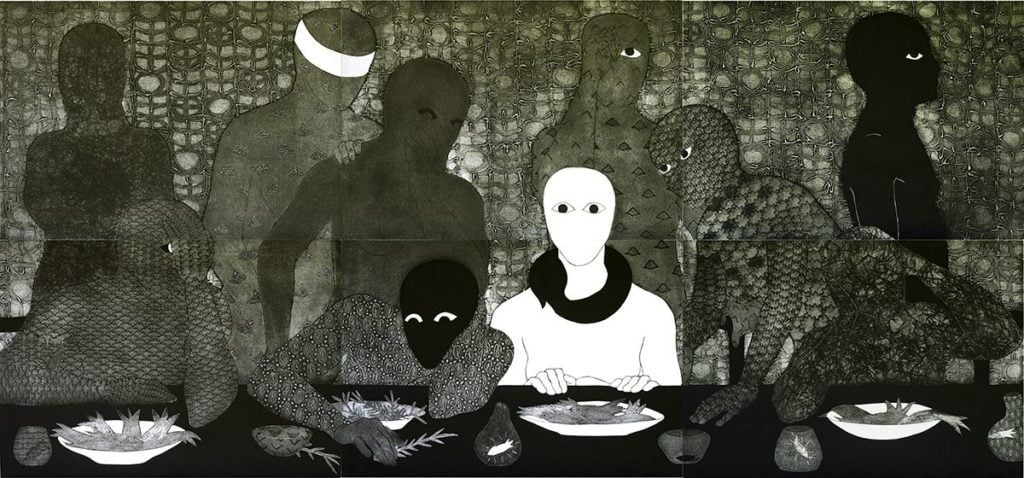

Belkis Ayón’s La cena (Last Supper) (1991), in “NKame: A Retrospective of Cuban Printmaker Belkis Ayón,” at El Museo del Barrio. Collection of the Belkis Ayón Estate.

Ayón appropriates religious iconography in her work, casting Sikán as the martyred St. Sebastian, or even more daringly, as Jesus Christ. In La Cena (The Supper) (1991), Sikán takes the role of the savior at the Last Supper, her almond-shaped eyes staring directly, captivatingly, at the viewer. At El Museo, there’s a brightly colored 1988 study for the work, as well as the final version, in stark black and white, and the cardboard matrix used to produce both.

By refocusing the male-dominated narratives of both Christianity and Abakuá on a female figure, inserting a woman into a central role in religious ritual, Ayón sought to rebel against traditional gender roles in Cuban society. “Sikán is a transgressor,” she wrote, “and as such I see her, and I see myself.”

See work from the exhibition below:

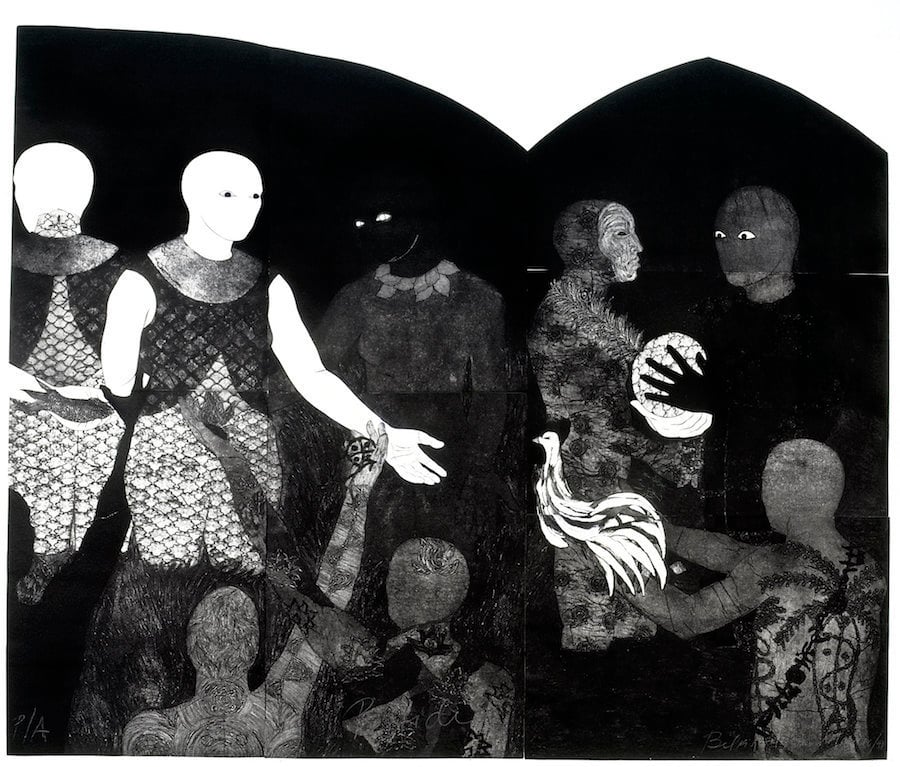

Belkis Ayón, Perfidia (Perfidy), 1988, in “NKame: A Retrospective of Cuban Printmaker Belkis Ayón,” at El Museo del Barrio. Collection of the Belkis Ayón Estate.

Belkis Ayón, La familia (The Family), 1991 in “NKame: A Retrospective of Cuban Printmaker Belkis Ayón,” at El Museo del Barrio. Collection of the Belkis Ayón Estate.

Belkis Ayón, Nlloro (Weeping),), 1991, in “NKame: A Retrospective of Cuban Printmaker Belkis Ayón,” at El Museo del Barrio. Collection of the Belkis Ayón Estate.

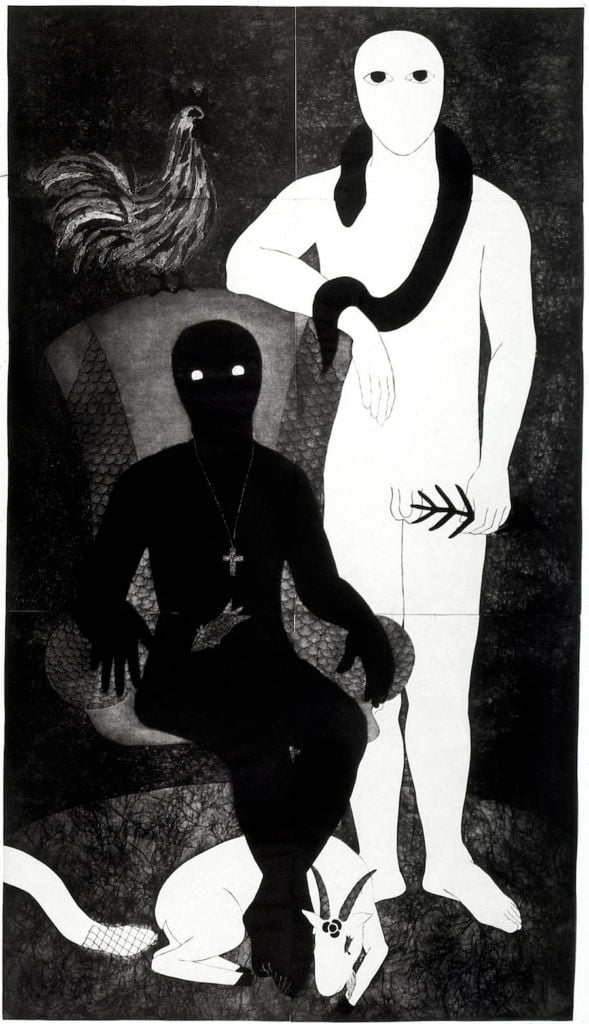

![Belkis Ayón, <em>Sin título (Sikán con chivo) (Untitled [Sikán with Goat])</em>, 1993, in “NKame: A Retrospective of Cuban Printmaker Belkis Ayón,” at El Museo del Barrio. Collection of the Belkis Ayón Estate.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2017/11/5866c8a81500002e00e9dc29-821x1024.jpg)

Belkis Ayón, Sin título (Sikán con chivo) (Untitled [Sikán with Goat]), 1993, in “NKame: A Retrospective of Cuban Printmaker Belkis Ayón,” at El Museo del Barrio. Collection of the Belkis Ayón Estate.

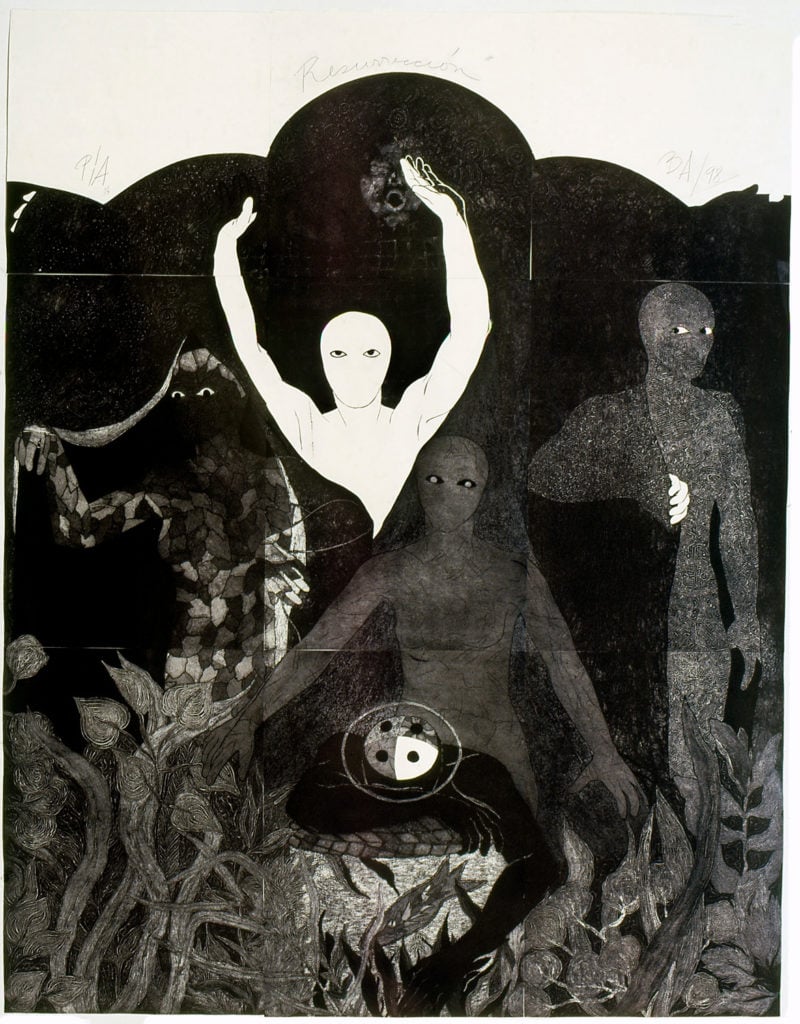

Belkis Ayón, Resurrection (1998), in “NKame: A Retrospective of Cuban Printmaker Belkis Ayón,” at El Museo del Barrio. Collection of the Belkis Ayón Estate.

“Nkame: A Retrospective of Cuban Printmaker Belkis Ayón” is on view at El Museo Del Barrio, 1230 Fifth Ave, New York, NY until November 5th.