For many collectors, art-buying is an activity carried out in private. For Bernard Lumpkin, to collect in private would be to defeat the purpose.

The former MTV executive has spent the past decade building one of the most vibrant private collections of work by Black artists. His holdings—which include examples by established artists such as Kara Walker, Kerry James Marshall, and Henry Taylor as well as up-and-coming young talents—are on view at his Manhattan apartment, which he opens up frequently to visitors, as well as at his husband’s law firm offices.

Now, highlights of the family’s holdings will gain an even bigger audience thanks to Young, Gifted, and Black, a traveling exhibition and publication of artwork from the collection, curated by Antwaun Sargent and Matt Wycoff. As art institutions across the country begin to reopen, the show is due to travel to Texas, Pennsylvania, and California.

The book, which will be published on September 22, offers a deep look at the Lumpkin-Boccuzzi Family Collection alongside an essay by Sargent situating Lumpkin in the long history of Black art patrons and an interview between Lumpkin and the Studio Museum in Harlem’s director Thelma Golden. (Lumpkin serves on the board of the Studio Museum, as well as on the Whitney Museum’s acquisition committee and the board of the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, among other museum roles.)

The collection, developed in partnership with (and financial support from) Lumpkin’s husband, lawyer Carmine Boccuzzi, aims to offer a model for how art can be acquired in ways that benefit the artists just as much as the collector. Ahead of the release of the Young, Gifted, and Black publication, Lumpkin reflects on his collecting philosophy, what drew him to art, and why he considers community to be inseparable from culture.

What aspects of your early life fed into your love of art?

With my father being African American and my mother being Sephardi Jewish from Morocco, I was raised with a holistic sense of identity. I was very aware of being “other,” combined with the reality that I “passed.” Even though I was aware of being different and having different sides, I was perceived by the world as being none of those things. So I was always interested in finding a way to explore and express that [paradox]. Art became a way for me to do that.

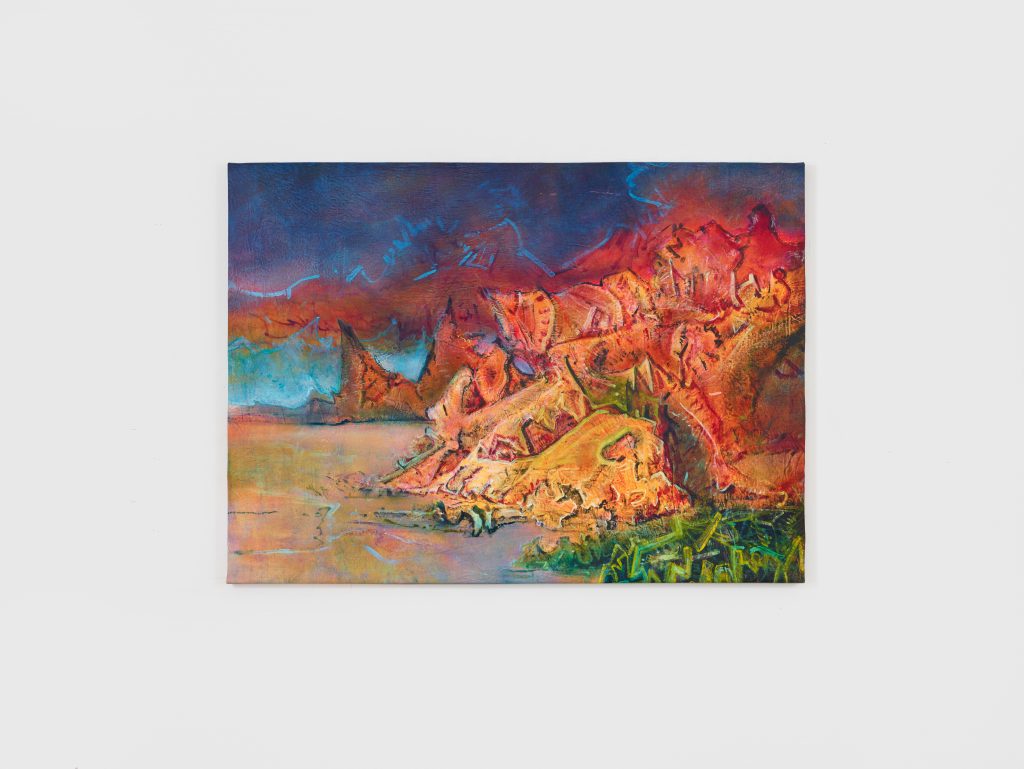

Henry Taylor, Rock It (2008). © Henry Taylor

Professionally, I was always working with artists or creative people. My first career was as a producer in the news department at MTV. I worked on social-issues shows. That was a time when MTV was a source of news in a way that it isn’t so much today. Out of that experience, I developed an affinity for working with artists, specifically on projects that had a larger social impact. Looking back now, my time as a producer at MTV really informed my thinking around how to be a patron, how to support artists, and how to engage the world through your work.

Through the combination of MTV, my parents’ experience with civic engagement and activism, and their emphasis on education, I realized that whatever I did had to touch on those things.

One of my earliest memories of art was not in my home or in a museum. My parents were not collectors—we didn’t have that kind of money. It was in the neighborhood where my father was born and raised, Watts. The Watts Towers is an amazing sculpture that was built in by Simon Rodia, an Italian immigrant. He built it from bits of glass and pottery that he found in the neighborhood. It had a big impact on me. It was my first experience of art that was in the community.

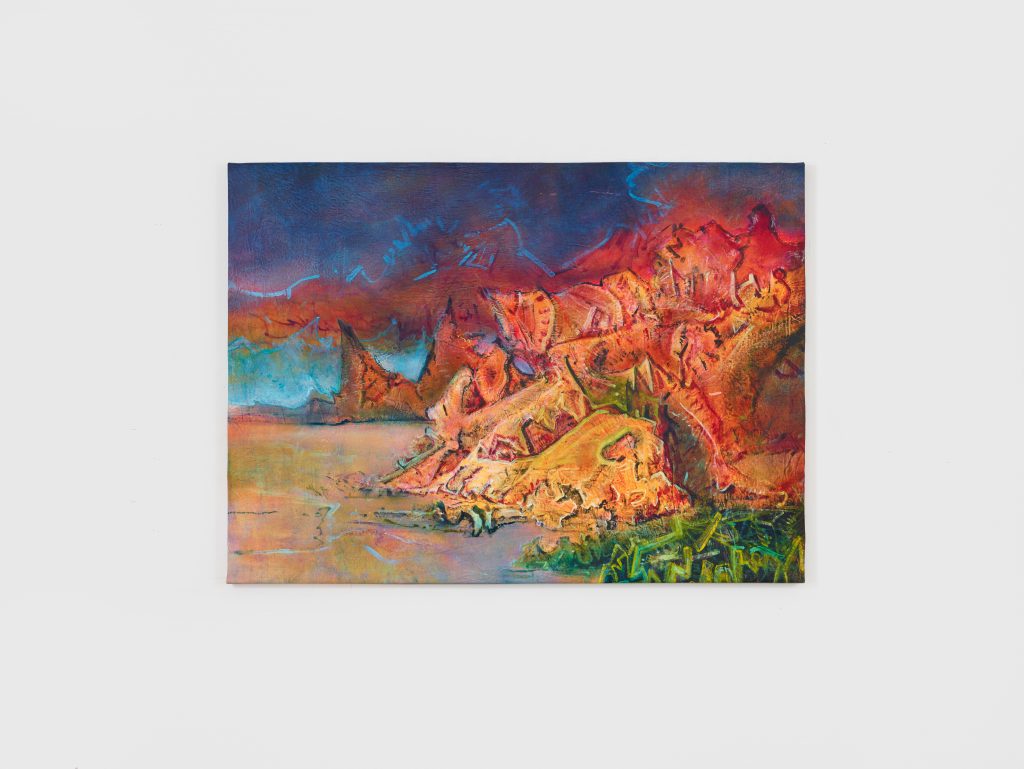

Cy Gavin, Underneath the George Washington Bridge (2016). © Cy Gavin, Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York / Rome

At what point did you begin to formally engage with art as a patron?

A turning point for me was when my father became sick with cancer about 10 years ago. I stopped working at MTV so that I could spend more time with him. It turned out that he only had six months to live, but I was grateful for that time. He told me stories about growing up in Watts, and of my grandparents and larger family.

At that point we [Lumpkin and his husband, Carmine Boccuzzi] had collected art but it wasn’t with a focus or purpose. I came back to New York after my father passed away and looked at the art collection while having conversations with him in my head. I thought to myself, “Which of these artists are really resonating with me now?” I felt different. I wanted to take my experience at MTV, in entertainment activism as it were, and do [the same thing] with this collection.

I also wanted to build a community around what I was doing. Some collectors are private and don’t show their work or share it with the world. I totally turned that on its head. I want people to see and learn about what I’m doing because it has this larger purpose.

What was the impetus for starting to collect in a purposeful way and when did the collection take on the mission it has today?

The collection starts from a very personal place. People often ask me, “How did you find your focus? How do you develop a focus and a passion?” Whatever your focus is, it should come from a place that has meaning for you. You’ll need that passion to carry you through. That passion is what people see when they see your collection.

Kara Walker, Untitled (1995). © Kara Walker

It became pretty easy once I decided to focus on artists of color. I wanted to tell stories I was interested in, in terms of my own family background and the conversations I had with my father about race, history, and what it means to be American, as well as conversations with my mother about being an outsider in America. She was never an American citizen and she always shared her feelings of being an insider/outsider in this country, which is something that drew me toward artists who were exploring that feeling of being American and not American—that tension one feels in this country when you are a person of color or from a different background.

The collection is referred to as a family collection. What does that mean and how does your family play a part in the collection?

With collecting art, you are constantly thinking of posterity, of heritage. I truly believe that I am just a custodian for these artists and their work. I am blessed and grateful to be able to care for it, support it, and advocate for it. I give it a good home and put it into the world, which is part of the [Young, Gifted, and Black] exhibition. That’s my role. From there, I’ll pass the work and hopefully the mission to other people, to other institutions. Part of that passing on is where the family part comes in. When Carmine and I are gone, the children in some way will hopefully continue this mission.

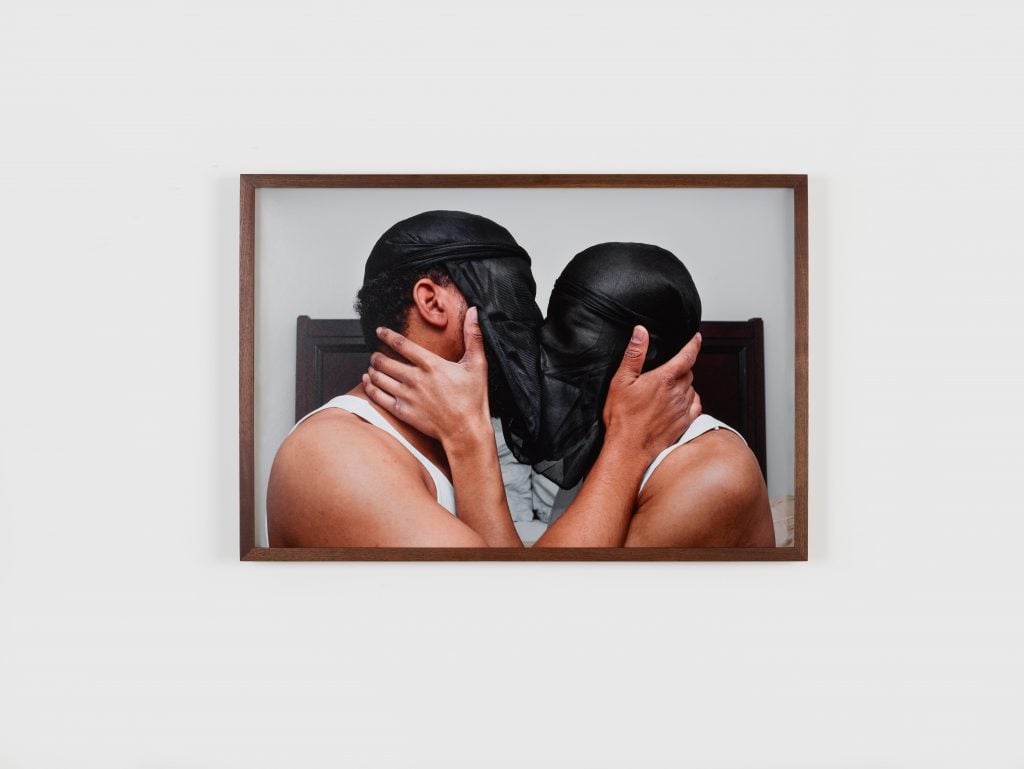

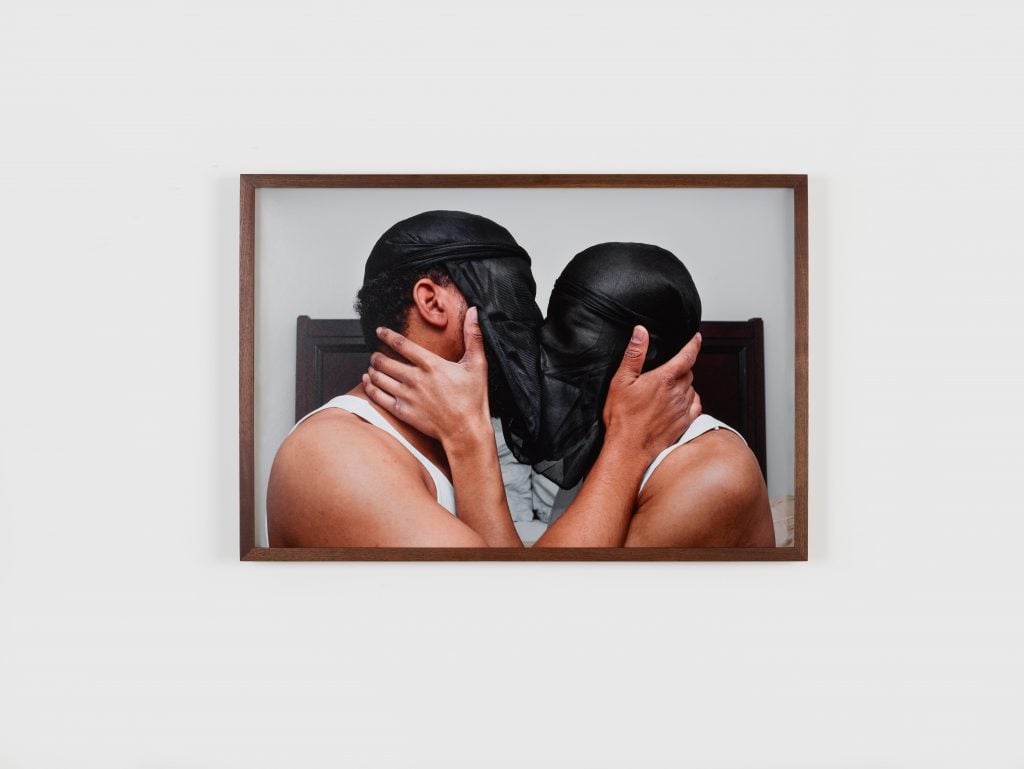

D’Angelo Lovell Williams, The Lovers (2017). © D’Angelo Lovell Williams, Courtesy of the artist and Higher Pictures

How do you decide on new acquisitions?

Sometimes if I’m faced with a challenge [through the work] or something new, whether it’s a challenge with the material or the medium, that motivates me. I try to support artists in depth at the beginning. I feel like that’s a way to demonstrate your commitment to a younger artist. If an artist is working in different mediums, I’ll try to acquire works in different mediums.

Cameron Clayborne, for instance, makes really interesting work about the body. It’s figurative and abstract, there’s a conversation with material that is interesting to me. He does performances with these inflatable plastic pieces that he shapes; he also makes work on paper. That’s an artist that you want to try and collect different kinds of things.

As a collector, I think you decide with a mixture of research and instinct, gut and brain. If you have already begun a conversation with an artist, it’s about going deeper. If it’s a new artist, it’s about, where do I begin and where do I see this going?

How do you view your role in the art world? What do you wish to achieve with the platform you’re creating?

Education, activism, and inheritance. With the exhibition as an example, the community aspect of what I do is so important. When it came to doing this exhibition and this book, I wanted to put that community to work in a different way. I could call on the curators that I’ve worked with over the years, have them participate. I could gather the artists whose company I’ve had the pleasure of being in for so many years and have them write about their work. I could also take this to other places. I love New York and it’s the center of the art world, but it begins to feel like preaching to the choir. I began to think about taking these artists, their vision, and their message to a wider audience.

There aren’t many ways an art collector can be an activist, but you can have a voice and you can use that voice. I serve on museum committees where I am often the only person of color in the room, or one of the few. I really try to advocate for what that means, whether it’s supporting exhibitions by artists of color, supporting a new curator who can champion those artists. I support the larger questions that are now being raised by museums. It can be done. It’s being done. It’s been done. A lot of institutions just haven’t taken notice or haven’t been incentivized to learn and start doing these things. Now is a great moment for that to happen.

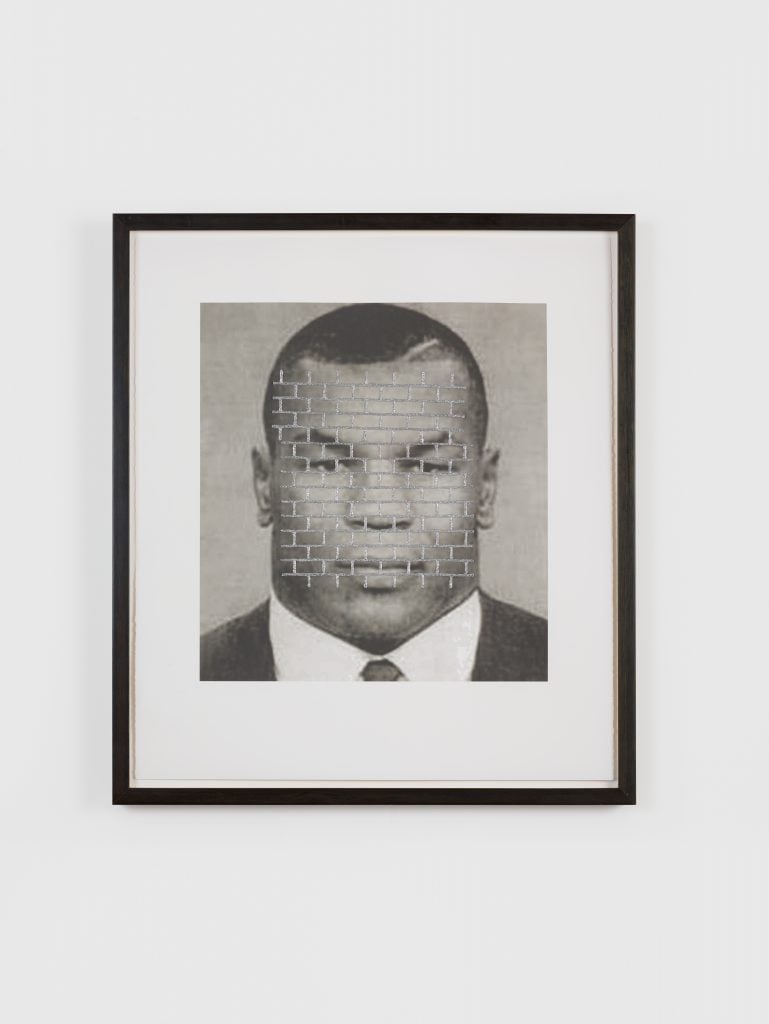

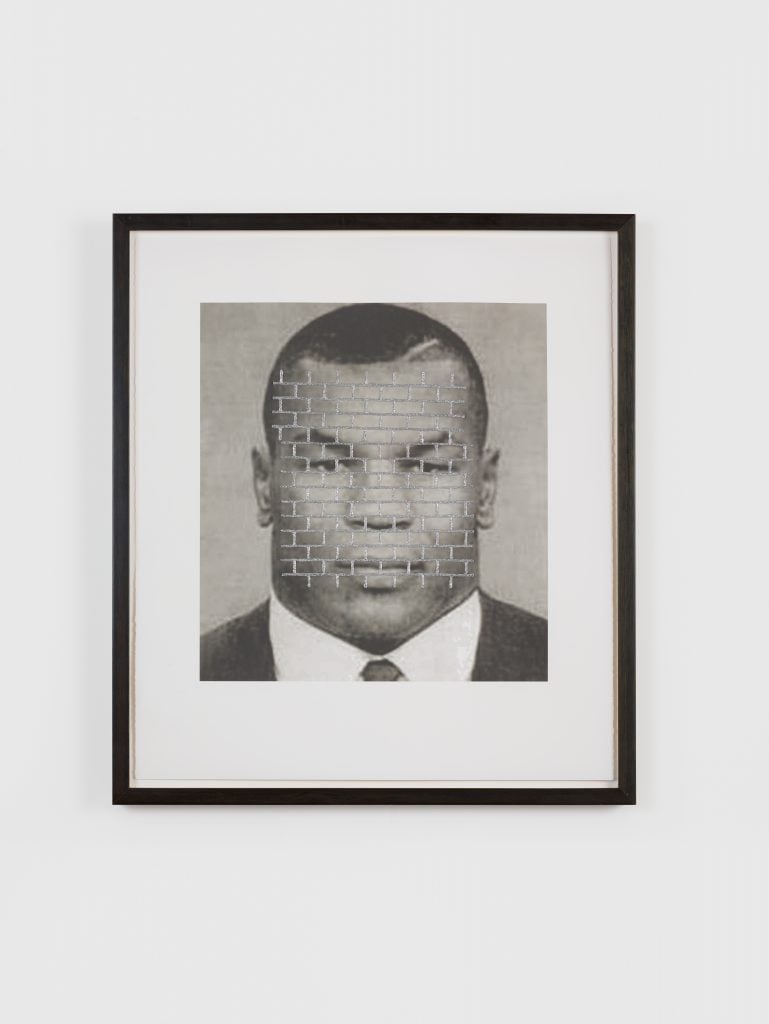

Derrick Adams, The Great Wall (2009). © Derrick Adams

My role is to get these images out there in as many ways as possible. What I hope to do is leave a legacy for other collectors and patrons, like the people who came before me. There’s a whole history of black art patrons. I’m working in a lineage which has given me a greater sense of purpose. I hope that other young patrons that come after me will continue that.

What is your hope with this exhibition and book? What does this moment mean for the collection?

This moment became something other than what it started as. When I started this project pre-George Floyd and the protests related to that, there was enough work to be done. Museums need to have a wider, deeper sense of what American art is. They need to be showing more artists of African descent. They need to have staff and boards that better represent the communities they serve. The book and the exhibition were always meant to reflect my effort to advocate for that, my own civil rights mission.

I hope that this book and this moment will contribute to the dialogue that’s happening around race in this moment. I hope it will expand and enrich that dialogue. I think that the images that these artists put forth in the world are different from what many people in this country are used to seeing of African Americans: images of pleasure and leisure, images of family, images of empowerment, images of hope and freedom. So often in this culture, particularly in the light of recent events, there’s a negative, stereotypical, and repetitive story about the Black experiences. I hope the works in themselves will show people a different view of what it means to be Black.