Art History

‘An Artist Truly at Peace’: Trailblazing West Coast Abstractionist Bernice Bing Finally Gets Her Due

The Bay Area-artist was overlooked in life. Now, 30 years after her death, the mid-century artist is having her powerful New York solo debut.

The odds were stacked against Bernice Bing, but she defied them anyway. She was an Asian American, a woman, and a lesbian in mid-century America. Her childhood had been tumultuous: Bing had been orphaned at the age of 6 and raised in mostly white foster homes, where she suffered abuse.

A quiet tenacity led Bing forward, however, and the San Francisco native (1936–1998) would become one of the most significant artists to emerge in the Bay Area in the mid-century generation. In a circle that included Joan Brown and Jay DeFeo, Bing would establish herself with her gripping abstractions which blended Eastern and Western influences.

Now, nearly 30 years after her death in 1998, the West Coast Abstract-Expressionist is getting her first New York solo exhibition with “Bernice Bing: Bingo” at Berry Campbell in New York (through October 12).

The gallery, which began representing the Bing estate earlier this spring, has organized a powerful introduction to the artist whose legacy has long been snubbed by the East Coast art world.

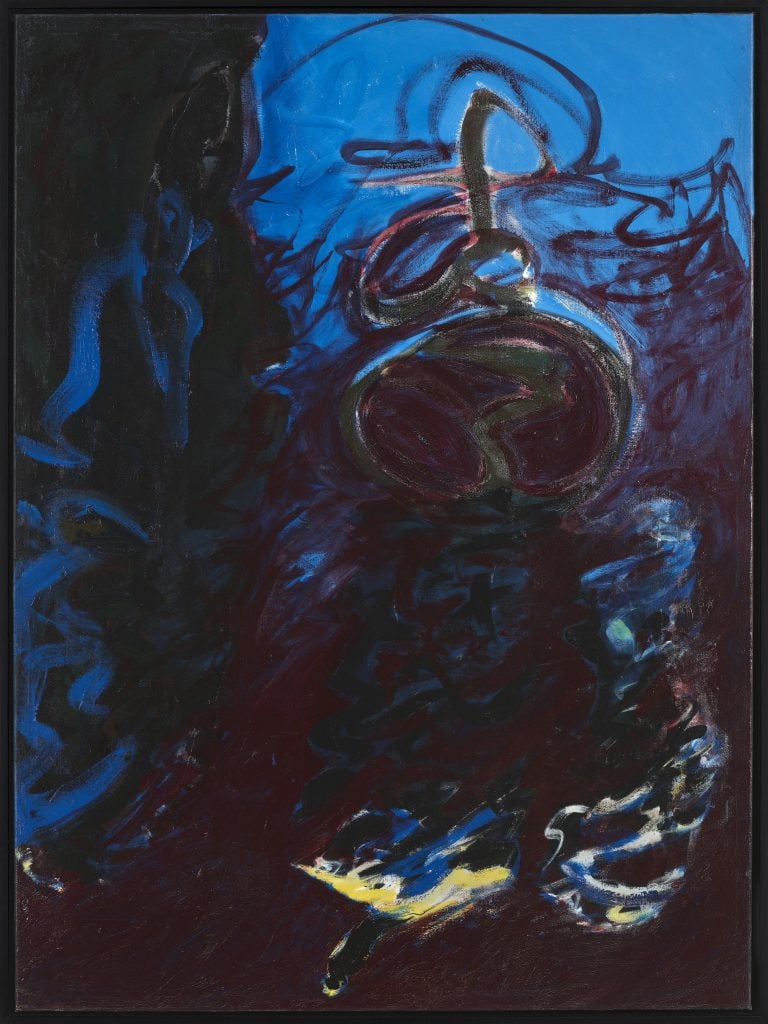

Bernice Bing, Untitled (ca. 1987). ©Estate of Bernice Bing. Photo courtesy of Berry Campbell, New York.

“I get goosebumps with this show. For Bing to persevere in this way and to come out in a positive light is a miracle after the childhood she experienced,” said Christine Berry of the gallery, “She became a community organizer. She was a Buddhist. She was an artist truly at peace.”

“Bingo” (which was Bing’s nickname) showcases more than 30 works from the 1960s through to 1998, the year of her death, and underscores her evolving approach to abstractions which drew from the canon of Western art history, the landscapes of California, and increasingly from Chinese landscape paintings, calligraphy, and Buddhism in the later decades of her life.

Courtesy of Berry Campbell Gallery.

Art had been Bing’s path into her future. In high school, she stood apart in her art classes, earning, remarkably a scholarship to the California College of Arts and Crafts. There she would study under Richard Diebenkorn (his influence can be seen in the steep horizontality of her painting Burney Falls (1980). She also studied under Japanese artist Saburo Hasegawa, who encouraged the young Bing to delve into her Chinese identity.

Born the daughter of a first-generation Chinese American, Bing remembered visiting her maternal grandmother, who had bound feet, along with her sister, from whom she would be separated in foster care.

“[Hasegawa] told her she didn’t know anything about being Asian and she needed to explore how it influenced her,” said Berry, “She took that to heart.”

Bernice Bing, Velazquez Family No II (1961) © Estate of Bernice Bing

Courtesy Berry Campbell, New York

Bing would transfer to the San Francisco Art Institute, where she ultimately earned her BFA and MFA. Generations (1961) is one of the earliest works in “Bingo” made when Bing was just 25 years old; the evocative painting shows Bing’s grappling with the gestural abstraction of the era.

That same year, Bing had her first solo debut at San Francisco’s Batman Gallery (“a beat poet type of place” Berry says which was tapped into the creative zeitgeist during its short lifespan). The show was generally well-received and encouraged the artist, fresh out of school, to continue her artistic pursuits.

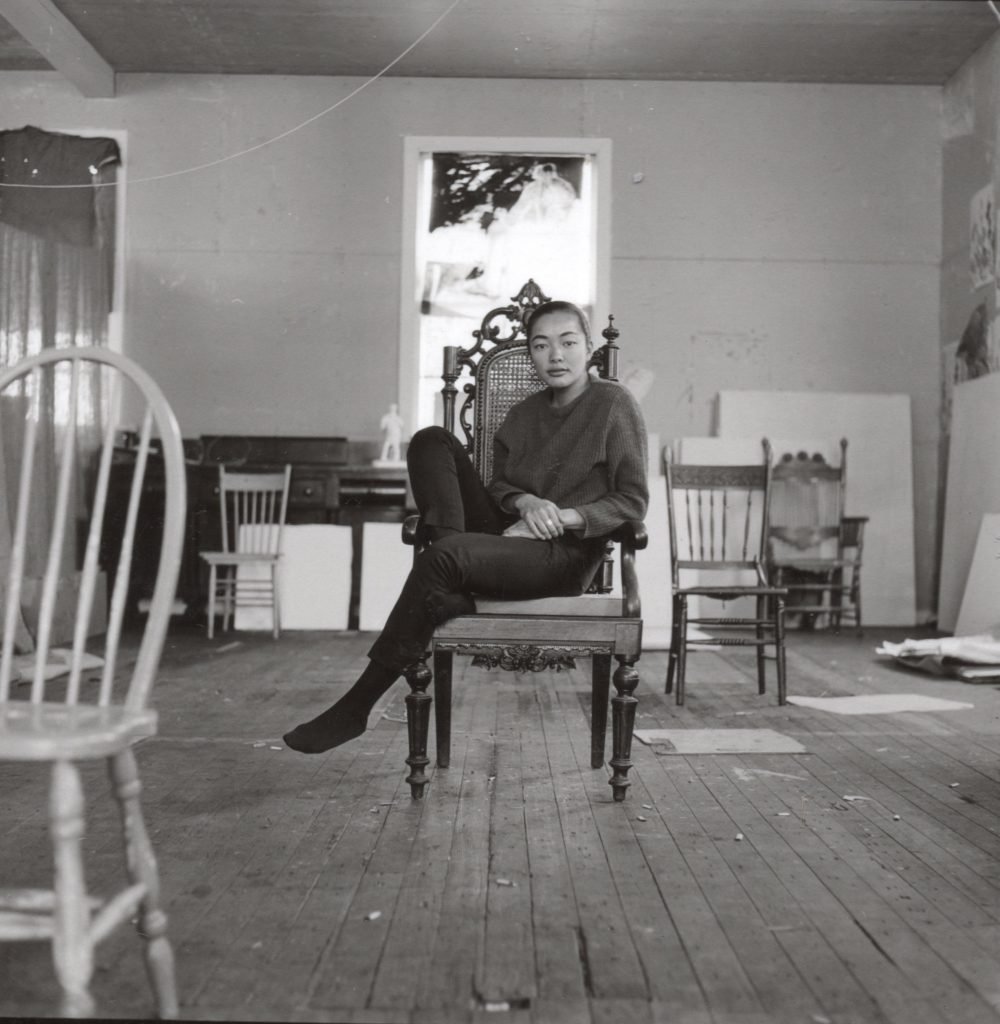

Bernice Bing in her North Beach Studio, c. 1961. Photo: Charles Snyder

Courtesy Berry Campbell, New York

Another pivotal early work is her Velazquez Family No II (1961) which shows Bing reimagining Diego Velazquez’s Las Meninas in abstracted forms. She did several works based on the Spanish master’s oeuvre, underscoring Bing’s wide-ranging metabolism of art historical influences. But the California landscape, even in abstraction, left its impression on her works.

Struggling to afford life in San Francisco, for three years, she lived out on a vineyard in Mayacamas in Napa Valley—and her paintings are influenced by the forms of the mountain ranges and the rich golden light. The star of the show is her stunning 1980 painting Burney Falls, which depicts the crescendo of waterfalls in Shasta County, California. The painting hovers on the verge of legibility before dissolving back into gestural abstraction, while already hinting at the influence of Chinese landscape paintings.

Bernice Bing, Burney Falls (1980) © Estate of Bernice Bing. Courtesy Berry Campbell, New York.

While Bing kept her artistic circles and her group of lesbian friends somewhat distinct, the artist certainly reckoned with how her identity placed her in the world. In a 1963 journal entry, she wrote, “I, being a woman, Asian, and lesbian in a white male system—where do I start to recover my reality?” One work in the show, Figurescape (1971) a bit of an outlier, hints at a sensuality of entwining female forms.

In 1980, finding limited success in the art world, Bing worked for several years as the director of the South of Market Cultural Center in downtown Chinatown, where she ran programs for troubled kids. “She started a program where kids in gangs would give up guns for paintbrushes. I think she looked at herself and tried to fix what she went through growing up,” said Berry.

Both Chinese and American identities would come into focus for the artist following a 1985 trip to China, Japan, and Korea. This journey deepened her interest in Buddhism (which she would embrace) and calligraphy, while her artistic approaches remained devoutly experimental. “It’s interesting that she gets into calligraphy later because it is about the brushwork. She is able to combine traditional calligraphy and this classic Abstract Expressionism and gestural abstraction at the same time,” noted Berry.

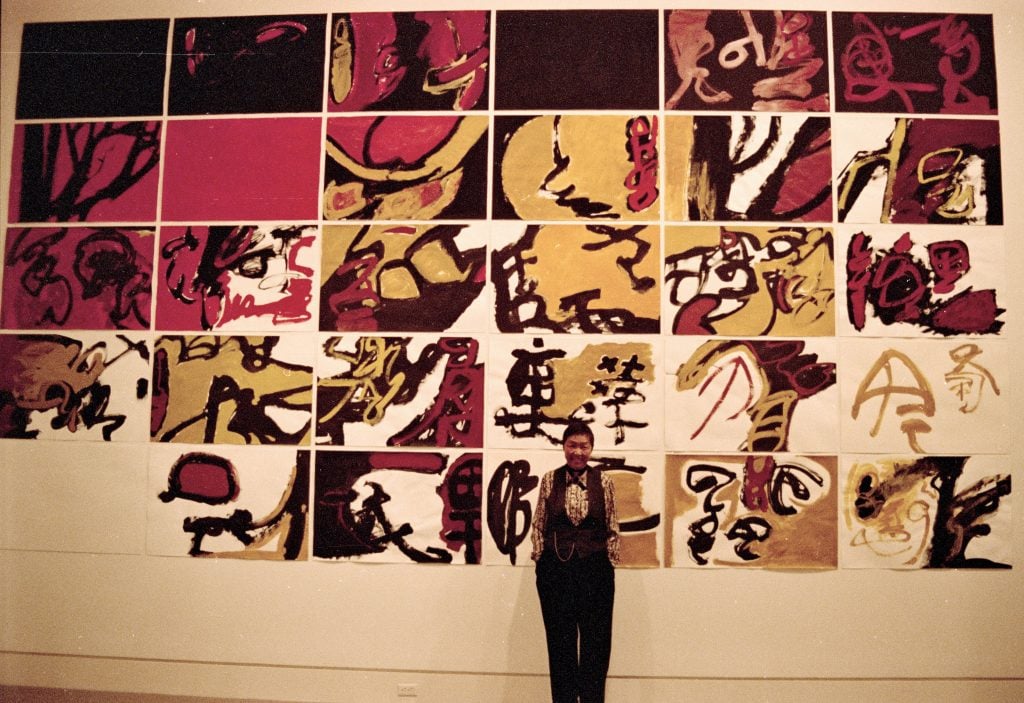

Bernice Bing with Quantum #2, included in “Completing the Circle,” Triton Museum of Art, Santa Clara, California, 1992.

Courtesy Berry Campbell, New York

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Bing created expressive abstractions that inventively played with Chinese characters, taking creative license of color and form that tied these works back to her abstractions from two and three decades earlier.

Untitled from 1986 depicts a vertical yellow rod glowing with squiggles of black white and yellow at its side; it recalls Chinese scrolls while at the same time calling to mind the light works of Dan Flavin. One of the most striking works in the show, Quantum 2 (1991–1992) shows her ingenuity. These mixed media works on paper are arranged in a 5 by 5 grid; Bing would replace the works as she sold them or gave them away.

Bing painted to the last months of her life in 1998, when she died at 62 from cancer. She had been a smoker and a drinker.

“There had been a local bar that had a Bingo-tini,” Berry recalled.

For the gallery, the exhibition has been a labor of love. Without a partner or child to whom she could designate her estate, Bing’s oeuvre has been scattered, with her friend Alexa Young inheriting her estate and attempting to place it as best she could.

“Her work has been very disseminated. We really had work to get these works together to put a good show, which is what she deserves,” said Berry.

Installation view “Bernice Bing: BINGO” at Berry Campbell, New York, 2024.

Over the past decade interest (and the market for) Bing’s works have grown exponentially—though the East Coast is still waking up. While the Denver Art Museum’s pivotal 2016 exhibition “Women of Abstract Expressionism” did not include Bing’s work, she earned an important nod in the catalogue.

A major museum breakthrough for the artist in 2019 when the Sonoma Valley Museum of Art staged the first retrospective of her work. On the heels of that show, in 2022, the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco presented another exhibition on her work and life.

But Berry believes her moment of arrival still has come to its fullest fruition. Last year, the gallery opened the show “West Coast Women of Abstract Expressionism” including Bing’s work. Since then the New York art world seems to have finally recognized her talent.

“Everyone has been clamoring for Bing since,” said Berry, “But there’s still so much more to say about her. We’ve really barely scratched the surface.”

“Bernice Bing: Bingo” is on view at Berry Campbell, 524 West 26th Street New York, New York, September 12–October 12, 2024.