Art & Exhibitions

Who Will Clinch the U.K.’s Top Art Honor? Inside the Turner Prize Exhibition

The sociopolitical meets the personal in works by Claudette Johnson, Jasleen Kaur, Pio Abad, and Delaine Le Bas.

The sociopolitical meets the personal in works by Claudette Johnson, Jasleen Kaur, Pio Abad, and Delaine Le Bas.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

The U.K.’s annual Turner Prize exhibition opens at Tate Britain in London on September 25, presenting all four nominated artists to the public before a winner is announced on December 3. If a thematic thread can be woven through the suite of exhibitions by Pio Abad, Jasleen Kaur, Delaine Le Bas, and Claudette Johnson, it must be how each reflects on the ways in which the histories we inherit continue to inform our lives.

Founded in 1984, the Turner Prize once thrived on controversy, stirring up heated debate about the nature of contemporary art while spotlighting future titans like Anish Kapoor, Antony Gormley, Damien Hirst, and Steven McQueen. Now in its 40th year, the award is a more low-key affair but continues to recognize important achievements by artists either born or working in Britain.

The winner will receive £25,000 ($31,000), with a further £10,000 ($12,500) for each runner-up. Last year the award went to Jesse Darling.

Installation view of Claudette Johnson, Protection (2024) and Friends in Green + Red on Yellow (2023) in “Turner Prize 2024” at Tate Britain from September 25, 2024–February 16, 2025. Photo: Josh Croll, © Tate Photography.

The standout nominee this year is portrait painter Claudette Johnson, who was selected for two exhibitions from 2023: “Presence” at the Courtauld Gallery in London and “Drawn Out” at Ortuzar Projects in New York. The 64-year-old artist emerged as part of the BLK Art Group in Wolverhampton in the 1980s but has only recently gained widespread renown after taking a multi-decade break from her practice.

In Friends in Green + Red on Yellow (2023), Johnson captures a charming sense of quiet camaraderie between her two sons. A new work, Protection (2024), is the latest of a series of self-portraits like Figure with Figurine (2019) that reference Picasso’s Les Demoiselles D’Avignon (1907) in their arrangement and use of space. Rather than othering West African sculptures and masks, however, Johnson explores her own relationship to these objects as a Black British woman.

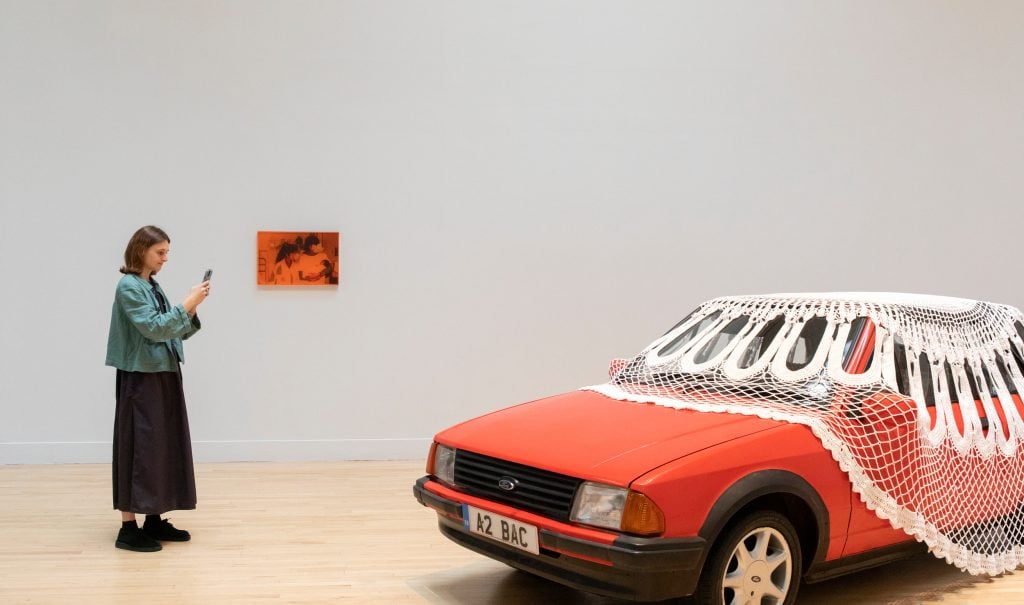

Installation view of Jasleen Kaur’s presentation in “Turner Prize 2024” at Tate Britain from September 25, 2024–February 16, 2025. Photo: Josh Croll, © Tate Photography.

Nominated for “Alter Altar” at Tramway in Glasgow, Jasleen Kaur‘s show layers found material to create an impressively evocative and fondly humorous record of her experiences growing up in Scotland as the daughter of Indian parents. The most literal example is an untitled series of salvaged family photographs that have been encased in resin stained the lurid orange of Irn Bru, the quintessential Scottish soda, and inlaid with torn scraps of chapati bread.

Which other objects store cultural memory? Among the everyday detritus on view is an open packet of soft mints, turmeric-stained fake nails, balls of hair, and old flyers for the Indian Workers Union. An unexpected poignance is introduced by the central installation of a vintage red Ford Escort covered in an oversized doilly, which Kaur said represents her “dad’s first car and his migrant desires.” These elements are all viewed within the context of sound work Yearnings, featuring the artist’s own vocals in the style of the Muslim Rababi tradition, the practice of which she sees as an act of political resistance.

Installation view of Pio Abad’s presentation in “Turner Prize 2024” at Tate Britain from September 25, 2024–February 16, 2025. Photo: Josh Croll, © Tate Photography.

If the gallery dedicated to Pio Abad has the unmistakeable atmosphere of a museum, that’s intentional. Nominated for “To Those Sitting in Darkness” at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, the Filipino-born artist has delved into the legacy of the many cultural artifacts that have been locked away in the store rooms of Western museums or flagrantly mislabelled for decades.

Abad’s meticulously researched artworks take these “icons of loss, of personal grief, of colonial grief,” out of the darkness and revisit long unexamined histories. In one example, a 1692 etching advertises the chance to view Giolo, a Filipino man who was bought as a slave and trafficked to England, where he was put on display as a curiosity before he died of smallpox. It is displayed beside Abad’s Giolo’s Lament (2023), a series of laser engravings on pink marble that in sequence depict the man’s arm reaching out.

“Giolo is at once monument and flesh, etching the forgotten man into permanence but also reminding us of his fragile humanity,” said Abad.

Installation view of Delaine Le Bas’s presentation in “Turner Prize 2024” at Tate Britain from September 25, 2024–February 16, 2025. Photo: Josh Croll, © Tate Photography.

A clear conceptual underpinning for the immersive installation by Delaine Le Bas is more elusive than it is with the other three artists, though the work apparently delves into the artist’s Roma heritage. She was selected by the judges for the show “Incipit Vita Nova. Here Begins The New Life/ A New Life Is Beginning,” at Secession in Vienna. The constructions of loose fabric decorated with colorful swathes of paint and fantastical figures will certainly be fun for attendees to walk through, but on their way out they are met with an ominous maxim scrawled in blood red: “know thyself.”

“Turner Prize 2024” is on view at Tate Britain through February 16, 2025.