Art History

Cheers! The Stories Behind the Three Most Extravagant Parties in Art History and the Paintings That Captured Them

Artists often did not just attend parties, they painted them for posterity.

Artists often did not just attend parties, they painted them for posterity.

Noor Brara

With the holiday season nearly upon us, entertaining may be on the brain—which parties we’ll go to, what we’ll host, how we’ll make the most of each, or how we’ll just get through them. But no matter what your attitude is toward holiday gatherings, browsing through fabulous images of the festivities is always fun—whether or not you feel up to partaking yourself.

In celebration of the season, we’ve rounded up three of art history’s most extravagant parties and the stories behind their creation, from an Edouard Manet painting featuring the get-togethers of high-society Paris to an Archibald Motley composition celebrating the swank and effervescence of Jazz Age shindigs.

Read on below to learn more about each one.

Edouard Manet, Masked Ball at the Opera (1873). Courtesy the National Gallery of Art.

Edouard Manet captures the glamour and revelry of Parisian high society in his painting Masked Ball at the Opera (1873). The artist, who came from a wealthy family, often attended gatherings such as this one, in which well-dressed men and women partied with showgirls at an annual ball held at the opera house during Lent.

According to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., which currently houses the painting: “There is little doubt about the risqué nature of the evening, where masked young women, likely respectable ladies concealing their identities, scantily clad members of the Parisian demimonde, and well-dressed young men all mingle together.”

Manet did a preliminary sketch of the scene while he was at the party and included depictions of his friends—many of them also creative types—as well as himself in the work. He is likely the blonde, bearded figure on the right, who peers out to meet the eyes of the viewer. At his feet lies a fallen dance card which bears the painter’s signature. The artist completed the painting in his studio several months later, and many of his friends, including the composer Emmanuel Chabrier, stopped by to pose for the piece.

And although the painting was rejected by the jury of the 1874 Paris Salon for being too naturalist—and likely too scandalous—it found a home in the collection of the famed opera singer Jean-Baptiste Faure.

Adolph Menzel, The Dinner at the Ball (1878). Image © b p k – Photo Agency / Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Jörg P. Anders.

Is there an art historical work more glittering and extravagant-looking than Menzel’s The Dinner at the Ball? The layered, light-filled painting depicts a party mid-meal at the Berlin Stadtschloss, or City Palace, where Menzel was a frequent guest at such events from the 1860s onward.

He would often chronicle his experiences in his artworks, focusing on guests’ interactions, incidents, and posturing throughout the evening. This work is easily the artist’s most detailed portrayal of Berlin society, their garb and glass-clinking, an incredibly precise and faithful recreation of the party. But look closely and you’ll notice that none of the individuals portrayed in the work have clearly identifiable features, nor is the room itself architecturally accurate—everything gets a little lost in the haze.

The Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin, where the painting now hangs, says it “conveys a picture of Wilhelmine society whose lustre Menzel was brilliantly able to convey, and yet whose ambivalence he did no more than register as an apparently neutral chronicler.”

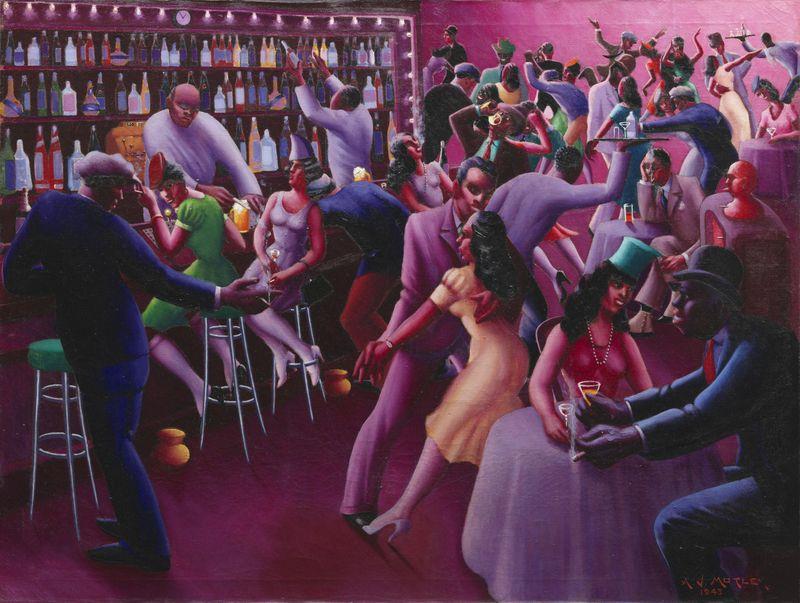

Archibald John Motley Jr., Nightlife (1943). Image courtesy The Art Institute of Chicago.

Jazz age Chicago painter Archibald John Motley Jr.’s Nightlife is one of the artist’s most celebrated works, featuring young, beautifully dressed partygoers enjoying drinks and dancing in the South Side neighborhood of Bronzeville. Over the course of Motley’s career, he sought to depict the energy and vibrancy of Chicago’s nightlife, and most of his paintings feature Black Americans. (According to a piece in the New York Times, during the last years of his life, Motley told Whitney Museum director Dennis Barrie: “I was too much interested in these night scenes where you find a lot of these people of my race, the places where they go.”)

In this particular work, a kind of purple haze floods the room (inspired in part by the lighting in Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks) while couples gather at the bar or at tables, where they converse quietly over a drink, or cut loose on the dance floor. A small clock at the top of the work reads 1 a.m. while the bartenders reach for colorful bottles and dancers stretch across the room in the back, altogether forming a line of palpable energy and conveying a sense of liveliness that jumps off of the canvas.