“We started out in 2008 as just a DIY group of artists who got together to make art, throw parties, and have music shows in a warehouse in Santa Fe,” Sean Di Ianni, one of the group’s cofounders, said at the press preview. “Now we have a team of painters and sculptors, graphic designers, lighting and sound artists, people working with augmented and virtual reality, digital artists and programmers, costumers and performers, and designers of all types.”

The project was an immediate sensation, and the company soon showed it had the fundraising chops to rival any buzzy start up, bringing in $17 million in 2018 and over $158 million the following year. Meow Wolf, which has always prided itself in having a social conscience, filed as a B Corporation, a for-profit business legally required to meet standards for “social and environmental performance.”

“Our mission is to inspire creativity in people’s lives so that the imagination can transform our world,” Di Ianni said.

As you might expect, however, the demands of a multi-million dollar company sometimes don’t align perfectly with high-born ideals. Growing pains have included a unionization drive from dissatisfied staff—and reports that those organizing efforts met with opposition from leadership—as well as a massive round of layoffs during the pandemic lockdown. Additionally, plans for a hotel and art experience in Phoenix and a location in Washington, D.C. had to be cancelled.

Despite these challenges, Meow Wolf’s leadership insists the company has worked hard to stay true true to its creative roots.

Today, seven of the original co-founders—Di Ianni, Corvas Brinkerhoff, Benji Geary, Caity Kennedy, Matt King, Vince Kadlubek, and Emily Montoya—are still with the company, which now boasts a staff of 900.

Collectively, these dreamy yet high-tech tableaux represent the latest chapter in something akin to the Marvel Cinematic Universe—a world characterized by strange inter-dimensional portals and vaguely sinister corporations armed with futuristic technologies.

With three permanent locations under its belt, Meow Wolf is beginning to talk more openly about the depth of its world-building, and how its writers have been weaving together the threads of an overarching story. The plot, it turns out, has been in development for years—although it’s perfectly fine with the creators if you experience Meow Wolf’s spaces on a purely aesthetic level, rather than combing through each and every room for clues.

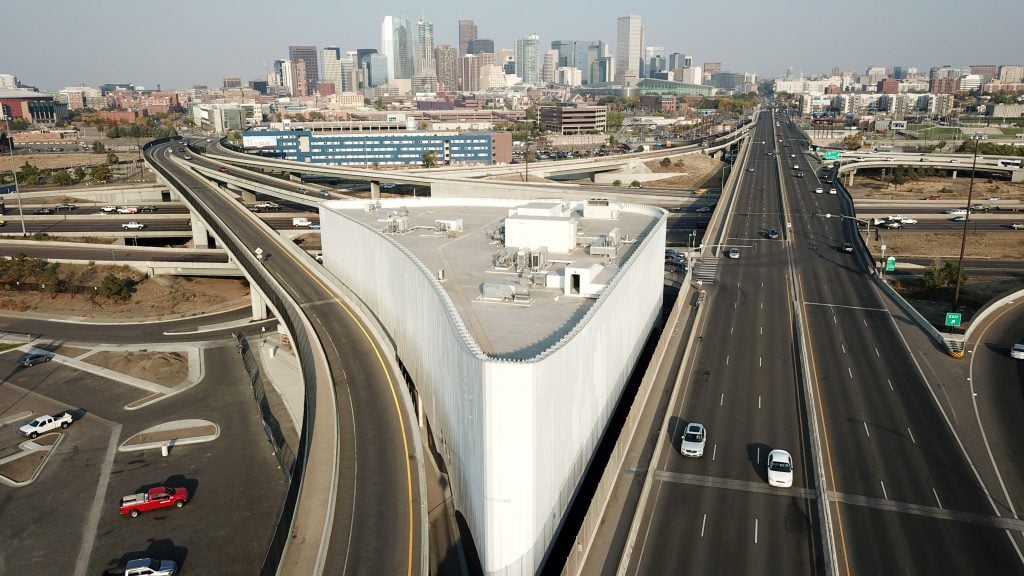

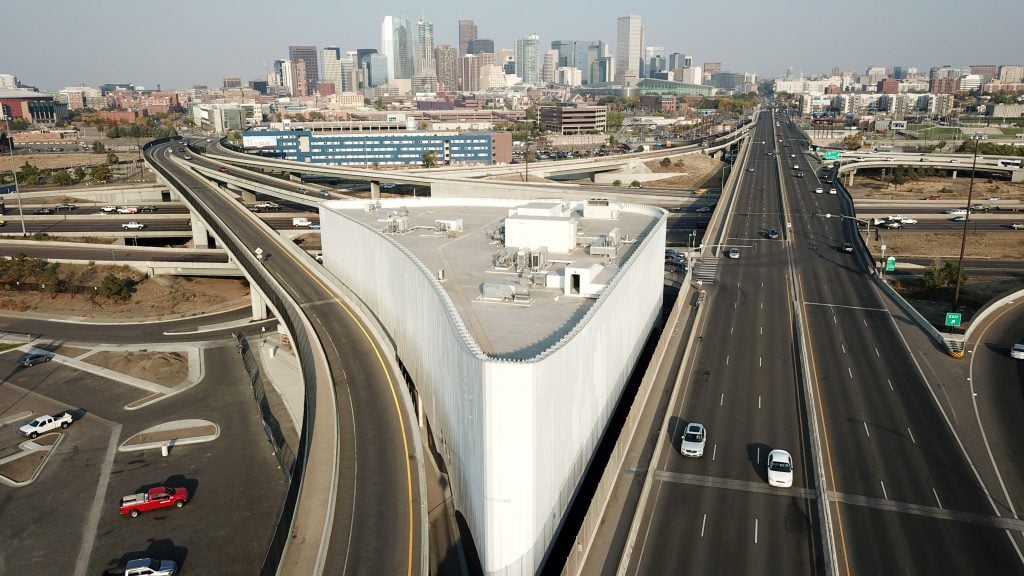

At the Denver opening, Artnet News sat down with two of the founders, Di Ianni and King, to talk about how the company and their roles in it have changed over the years, the challenges of building Convergence Station on an oddly-shaped plot of land between two arms of freeway overpasses, and whether what Meow Wolf does is still art.

You actually constructed the building around some of the largest installations, which were lowered into the foundation by crane. What was it like having a custom-built structure for the first time?

Di Ianni: We chose the site because it’s an amazing form of urban infill. Who else is going to build here? And what is it going to be? Maybe a storage facility? So I actually love this site, because we could use its parameters to determine the awesome shape of this building. It takes more time, but it can be helpful to respond to the space.

There’s also environmental considerations on both sides. In some cases, adaptive reuse can be less environmentally efficient.

King: Having all new materials, even though it seems less efficient upfront, the maintenance of that building needs a lot less energy. So a building like this actually has a much smaller environmental footprint in the long term.

Meow Wolf Denver. Photo by Robert Pineda, courtesy of Meow Wolf.

How did the construction process go?

Di Ianni: One of the challenges with this project is that we had 70 scheduling delays. And every time there was a construction delay, that led to delays for the artists. That will happen in every construction project—but one that’s built between these crazy highway overpasses, and has the level of integration and complexity as this one, plus doing it in the middle of the pandemic?

It’s been a pretty interesting professional development experience, just seeing the level of coordination that’s required between contractors and city permitting and artist materials, to make sure everything meets the fire code.

King: The fact that we’re 10 feet from the highway and it’s a five-story building with no windows above the first level for firemen to get in, that triggered literally the most restrictive type of fire code in the entire country.

It’s that kind of thing that we never could have budgeted for at the beginning. We were limited to a type and quantity of fire-rated materials where the price just skyrockets. Our collaborating artists had never worked within these really rigid material constraints—and we found this stuff out after we had already contracted with them.

Di Ianni: A lot of the artists had never done work like this all, maybe never had a contract or shown their work professionally at all. There was a big learning curve, but every single artist who signed up to work on the project has completed their art. A pretty huge cohort all got to the finish line, which I think is pretty impressive. And we’ve codified what we learned from the process for future projects.

The Meow Wolf Workers Collective is pushing to unionize. Image courtesy of the Meow Wolf Workers Collective.

Like many art organizations, Meow Wolf has seen staff members organize in recent years, but there’s been a sense that the company has not been supportive of that effort. I read in the Denver Post that a job posting recently listed discouraging organizing in non-unionized portions of the company as part of the responsibilities.

Di Ianni: That was horrible. That job posting was not in any way a reflection of how we want to approach the union.

King: And that was from someone who is no longer with the company.

I am personally sitting on the company side of the [collective bargaining] negotiations. We have two different perspectives, but we all want what is best for the people that work on this thing. The only way that this is going to work and get bigger and become more impactful, is if the people who are making it are not only happy, but passionate about coming to work. There’s just a difference of opinion on how we go about that.

Di Ianni: Some of these people have been our friends for 15 years. There’s not an anti-union stance. I see the union as an opportunity. I think if we can communicate and work together, it’ll make us stronger. It’ll make us a better organization. I think that’s what the union wants, and I’m definitely aligned with that. And I’m hopeful that this [Denver] project can symbolize what’s possible—if we can do this, we can come up with a really awesome contract, right?

The lead artists for Numina, one of the four Converged Worlds at Meow Wolf Denver. Photo by Kate Russell, courtesy of Meow Wolf.

It’s becoming pretty clear that you are building your own version of a Marvel Cinematic Universe, so to speak. When did you decide to do that?

King: Honestly, we’ve been talking about this kind of stuff loosely since we started. But a lot of it was pretty back-burner high-level ideas. We never got too deep into talking about it until we were able to open the House of Eternal Return. And once the house opened and we proved that the business could be successful, then we really started digging into those ideas.

Di Ianni: And what’s great about it is that we’re not creating representations of existing intellectual property. We are charting this really crazy course, and this story has all this opportunity to go in all these weird places.

Story-wise, is this a dystopia—is it is a dark Meow Wolf universe—or is it a hopeful tale of what could be?

King: The story has so many tendrils that will break off in so many ways. But what we want is for people leaving to walk out questioning what is real, what is reality? Who am I, and what am I, what can I really do to make a positive change on the world? We’re not dystopian, that’s not our outlook. We don’t want doom and gloom.

Ice World at Meow Wolf’s Convergence Station in Denver. Photo by Kate Russell, courtesy of Meow Wolf.

But one of the Convergence Station worlds is the ice planet Eemia, and it’s been dead for 1,000 years…

King: But at the same time, the people on that planet were led by a scientific order that holds all the ancient information and mythology, and they were super hopeful. In a way, that relates to where we are now, because a lot of people in our world think that we are just totally fucked, you know?

And it is a smaller group of people who are actually saying that, no, it’s not too late. We haven’t run off the cliff. And we have the ability to spark the imagination and then turn this thing around. Eemia might seem on the surface doom and gloom, but if you really dig into it, it is hopeful and we will resolve their story in the future in a positive way.

Di Ianni: My favorite portal at a Meow Wolf show is the one that leads to the outside world. Because that’s the one where suddenly you’re seeing everything in slightly different ways. That’s the hope.

King: The world out here is actually the most surreal. It is the craziest one. We have just become so numb to it. We could never compete with making something that’s as psychedelic as the real world. The human experience of being a spiritual entity trapped in this weird little decaying meat sack—that’s pretty fucking weird. So let’s remember how special and exciting and crazy it is just to be alive.

We’ve just been so complacent for so long. But we are the only ones that are making up our world. And if our world sucks, it’s because we are complicit in allowing that to happen.

The big mission of Meow Wolf is how do we come together as people and change our world for the better? We’re doing it through art, because that’s all we know, but hopefully we inspire people in all different fields to help share in that mission.

Di Ianni: A lot of immersive experiences right now are all happy. There’s this sort of tendency towards escapism, to leave the world behind for this space that is saccharine and sweet. We really don’t want that. We don’t want to be that kind of experience.

King: Disney’s mantra is “the happiest place on earth.” I think if we had one, it would be “Meow Wolf: existentialism.” We’re going to show you that life is pain, but in that pain, there is beauty and wonder.

Di Ianni: And it should be nuanced, right? There should be all kinds of gray areas. There should be happy and hopeful things and fucking dark things. Blurring that line is part of what we’re doing.

The entrance to Meow Wolf’s Omega Mart at Area 15 in Las Vegas. Photo courtesy of Meow Wolf.

The Meow Wolf narrative is not written down and there’s no official guide to the plot—although fans have started building a Meow Wolf-pedia explaining everything. Are you considering publishing a written story?

Di Ianni: There is so much stuff going on on Reddit right now! There are these deep divers who explore the narrative and have really found out a lot.

We put up billboards around the city to promote the launch of this project. But for the text, Chadney [Everett, the project’s senior creative director] created this kind of alien language with made-up characters. Within hours, people had deciphered the whole language and translated it on Reddit.

King: Recently, a YouTuber figured out the entire central narrative of a Vegas exhibit and made this long video explaining all of it in outrageous detail. And a lot of it is not on the surface—you have to do some serious digging to unearth some of the stuff he was talking about.

There’s no maps inside, we don’t tell you where to go, and it’s totally open-ended. That doesn’t mean we’re not going to publish something some day, but we don’t currently have those plans. People can be a part of an online community where they start to figure it out together.

Di Ianni: That makes it more participatory. Part of that is the mystery of the story, part of it is the way you navigate physical space, and part of it is that we’re building this story as we go.

King: There are definitely holes that we don’t have all the answers for either. It’s not all figured out. That’s a funny thing, hearing people come up with theories that we never thought about. You think, “Oh, that’s actually pretty good.”

How many hours would it take to understand all the mysteries of Convergence Station?

Di Ianni: To use the QPASS card is about a two-hour experience. It’s not linear, but there are rewards and reveals. But that’s just one layer of it. There’s hundreds and hundreds of hours altogether.

King: We know that it might be a smaller group of people who actually participate in the story and learn it all. We understand that. And we’re okay if people walk in and have no idea what’s going on.

Di Ianni: I don’t know if we struck this balance, but people should feel totally comfortable just wandering through it. That’s a way of interpreting the world too, the sensory, kinesthetic experience.

Despite your success both with investors and with the general public, some people in the more traditional art world have been quite dismissive of Meow Wolf.

King: It’s always been like that, from day one.

Steven Lucero and Molina Speaks, Indigenous Futurist Dreamscapes Lounge at Convergence Station, Meow Wolf Denver. Photo by Kennedy Cottrell, courtesy of Meow Wolf.

Is that frustrating? Are you looking for art world acceptance?

King: No.

Di Ianni: Well, hold on. I don’t think we’re like, “No, we don’t want to engage with the art world.” But we’re okay if the art world has criticisms or doesn’t like us. We very intentionally want to be accessible to a wide audience, walking that line between art and entertainment. We want people to come and experience this thing. We consider what we do to be art—very much. But if the art world doesn’t like that, that’s fine.

King: We both come from an art world background. When we first started Meow Wolf, a lot of our aspirations were more art world-related, because what’s what we knew as artists.

But when I go into a very high-end gallery and I am ignored by a gallerist because I don’t look like I have the money to buy an expensive artwork, that feels elitist to me. That’s a part of the art world that I disagree with. It is a turn off for us. But at the same time, there is a network of institutions that house and support types of experience and visuals that have impacted me and influenced me and directed the entire course of my life, because I’ve been inspired by them.

Looking at where we are right now as species, we’re far more geared towards entertainment. We need to direct our art to be more approachable, so we can actually use it to spark a conversation, and make an impression and educate people. That takes a different shape than what I personally think the art world is there to do, because the art world—or should I say the art market—is there to fucking make money for themselves, not to change anyone’s mind.

Meow Wolf Denver. Photo by Robert Pineda, courtesy of Meow Wolf.

There’s a lot of money behind Meow Wolf as well, though.

King: Totally. I’m not saying money is a bad thing. Money is something that is here and it’s a construct in the same way art is—it is a construct of the human experience. It can be used as a tool to perpetuate an aspect of humanity that is negative and self-serving, or it can be used as a tool to help spread wealth into the larger collective body. And I personally believe the art market is very self-serving. We want to use it to make more of a community.

Di Inanni: I think the art world is a complicated thing. It’s easy to talk about it like it’s a monolith, but it’s not. The themed entertainment industry is a weird, complicated thing, too. I don’t think we belong to any of those industries in any perfect way whatsoever. I think we’re pretty unique. And we’re okay with that.

Since the House of Eternal Return opened, there’s been a lot of interest in the art world in trying to channel some of the magic of Meow Wolf. That immersive experience, which my colleague Ben Davis dubbed Big Fun Art, is something more museums and galleries are interested in exploring.

Di Ianni: It isn’t a new thing, by the way. The Catholic church has been using immersive experience for a long, long time. But you’re right. There’s Super Blue and other moves by the art world to embrace immersive experience in a different way than maybe how it emerged in the 1970s as an anti-commodification movement.

It is interesting to see that revolution. I think some of the Big Fun Art, if we want to call it that, is more engaging than others and more meaningful. Some of it is just an Instagram backdrop.

The Salwan at Meow Wolf Convergence Station, Denver. Photo by Kennedy Cottrell.

Do you think you will ever have a Meow Wolf museum show?

Di Ianni: Maybe!

King: If the right situation presents itself, yeah. Right after the house opened, I was working the front desk and a woman came in and said, “I’m from the Art Institute of Chicago.” I was like, “Oh sweet, let us know what you think.” And she literally went in and five minutes later she walked out of the exhibition, threw her hands in the air, exclaimed across the entire lobby, “Where’s all the art?” and walked out.

That is some people’s mindset, right? They see what we are doing as not being aligned with everything they personally believe to be art. And that’s totally fine. Art is subjective. You don’t have to think what we’re doing is art. When I sit in fucking meetings and I look at spreadsheets, I don’t even always think what we are doing is art, right?

Our intention purely is to be expressive of our condition and our thoughts and the times that we live in, and that resonates to me in the way that art has always done throughout history.

Meow Wolf Omega Mart in Las Vegas in the final stretches of completion. Photo courtesy of Meow Wolf.

Di Ianni: We were talking earlier about what happens when you leave this place. If we can get somebody to look at a piece of trash differently, or think differently about what a parking meter does, or like, solve climate change, that’s all part of the same kind of process of activating your imagination and connecting to the human condition that I think maybe is art.

If everybody doesn’t connect to that, if people need a white cube gallery to call it art, that’s fine. And there’s a place for that. I’m not anti-art world.

King: Neither am I!

Di Ianni: It’s just nuanced, right? There’s such a tendency to have black and white conversations about stuff, but it’s not so dualistic. The whole thing is an art project—the organization, the company, the business, the relationship with the union. This is what we do. It’s all part of the art project.