Art World

‘Like’ Art: 7 Masterpieces of Social Media Art That Will Make It Into the History Books

As Facebook, Twitter, and other platforms transform the world we live in, younger artists have harnessed social media to make great art.

As Facebook, Twitter, and other platforms transform the world we live in, younger artists have harnessed social media to make great art.

Dylan Kerr

![]()

Whether you like it or not, social media is an integral part of the fabric of contemporary life. Politicians’ Twitter posts have international implications; memes from Reddit form the bedrock of popular culture; brands compete for screen time alongside forgotten friends from high school; sharing selfies is now de rigueur for everyone from your preteen cousin to your grandmother; relevance is measured in followers and likes; and news, real or otherwise, is endlessly cycled, discussed, distorted, and sometimes even made on sites like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and more. Social media is more than just a generator of attention-sucking disturbances that flash into view and just as quickly disappear: It’s also how some two billion of us keep up with our friends and family, network with our colleagues, form and reform our political opinions, and generally express ourselves in a world that is more interconnected than ever before. Reckoning with the 21st century means, at least in part, reckoning with social media.

It’s shouldn’t come as much of a surprise, then, that artists (a famously curious bunch) have begun experimenting with this novel medium, teasing out its hidden implications and sending up its more baffling tropes. Born out of the ‘90s net art movement, where innovators like Heath Bunting and Yael Kanarek looked to the newly available World Wide Web as a site (get it?) for artistic experimentation and performative social connection, as well as the “surf clubs” of the early aughts, today’s crop of social media artists work within the confines of the corporate-controlled social media sites that structure our daily lives in an effort to distort and question exactly those confines. Here, we’ve rounded up seven of the most interesting and impactful social media projects of recent years for your perusal, which are united by a shared taste for fakery, manipulation, withholding, and irony. Keep them in mind during your next bout of compulsive app scrolling.

Stills from Petra Cortright’s WEBCAM (2007). Courtesy of the artist.

Uploaded to YouTube just two years after the video-sharing site was launched, Cortright’s VVEBCAM is an exercise in simplicity: the artist gazes blankly into a webcam (or, really, at the screen beneath the cam) as Ceephax’s “Summer Frosby” plays off of her computer and a range of cartoony stock effects (dancing pizza slices, falling leaves, etc.) flash across the screen. She looks, above all else, slightly bored, barely engaged with whatever she’s looking at onscreen but just interested enough to keep on looking as the images begin to flicker by faster and faster. The upload itself is tagged with hundreds of keywords, mostly irrelevant to the content of the video, that serve to bring in more and more viewers searching for unrelated content. (These tags eventually became the video’s downfall; YouTube removed the video in 2011 based on the “offensive” nature of some of them.)

Despite its straightforward presentation, Cortright’s work is now considered an early reworking of the self-objectification central to what we now might term “selfie culture,” but with an important twist: The artist is looking back with the same barely-there expression of the passive video viewer. Social media content may be a vital aspect of our day-to-day existence, but VVEBCAM highlights some of its inherent banality.

This collective project, spearheaded by Brad Troemel and Lauren Christiansen along with Joshua Citarella, Spencer Longo, Haley Mellin, Rachael Milton, Jesse Stecklow, Artie Vierkant, Andrew Norman Wilson, and submissions by thousands of other artists, is in part an attempt to answer an age-old question: “what is art?” While philosophers and artists have floated answers ranging from “the imitation of nature” to “literally whatever we say it is” over the years, the Jogging crew came up with their own novel definition: “stuff that’s presented like art.” In response to the rise of online contemporary-art roundups like Contemporary Art Daily and e-flux that were then quickly becoming the main conduits for viewing art from around the world, this group established a submission-based Tumblr page to share similar images.

There was, however, one big (or perhaps not so big) difference: Their posts were largely mockups, constructed using Photoshop to look like so many bona fide artworks of the time (messy, pop-culture-laden sculptures photographed against the clean white walls of a gallery and labeled with a title, medium, and artist name) without going to the trouble of physically realizing them. As the critic, curator, and current Postmasters Gallery director Kerry Doran writes in her 2017 essay “There’s No Business Like…,” this constituted “a tongue-in-cheek response to the newly forming reality that exhibitions would primarily be experienced through their documentation: Why make an object for the sake of being photographed when the tools exist to fake it?”

The artist Jayson Musson, still from ART THOUTZ with Hennessy Youngman (2010). Courtesy of Youtube.

Though arguably just as much a work of art criticism as it is an art project, Jayson Musson’s 25 YouTube videos released under the moniker Hennessy Youngman stand as vital documents of the shift in contemporary art from rarefied academic discipline to career-driven striving, a change precipitated in no small part from the rise of social media itself. In the videos, Youngman, bedecked in a cartoon-themed flat-brimmed cap, delivers his own scathing take on the artists and art practices so often exalted in the university setting, like relational aesthetics, institutional critique, and Post-Structuralism.

Such disdain for one’s predecessors is of course standard for any self-respecting young artist, but Youngman’s blend of bombastic humor and political acuity coupled with his riff on “YouTube personality” tropes then coming into being (think direct webcam addresses, outlandish statements, and simple but effective graphic overlays) makes his jabs at the establishment memorable. (I challenge you to watch his video on Bruce Nauman and not think of Youngman’s take every time you see the venerated video artist referenced.) Perhaps his most important commentary comes from his 2010 video “ART THOUGHTZ: How To Be A Successful Artist,” which includes such helpful steps as “be white” and “be a white male,” and has an unforgettable disquisition on painting a flower. If only the advice weren’t as relevant today.

Stills from Sara Ludy’s Projection Monitor (2010–2014). Courtesy of the artist.

Remember Second Life? For a while after its 2003 launch, it seemed that the virtual world created by Linden Lab would be the one to finally make good on the promises of ‘90s techno-utopians, who saw the Internet as a place of unbridled creative expression and social connectivity where anyone could reimagine themselves as anything else. But, like so many other examples from the brief history of the Web, its users gradually got bored and left, or else turned to increasingly elaborate forms of avatar-on-avatar eroticism, leaving Second Life as a depopulated relic of its former glory.

Into this emptying world strolled Sara Ludy, whose “Projection Monitor” project documents its more mundane aspects. Ludy uses a real camera to shoot images of Second Life landscapes and interiors displayed on a computer screen, adding an extra layer of remove to the content being photographed, before posting them onto the project’s Tumblr page. While many a think piece has commented on the bizarre nature of the simulation and the social interactions it engenders, Ludy focuses instead on quieter scenes, almost always devoid of avatars, that are at once peaceful and slightly creepy. If the other social media projects on this list attempt to fit themselves into vibrant online ecosystems, Ludy is perhaps a kind of e-archaeologist, documenting a forgotten civilization long after its denizens had passed on.

Installation view of Constant Dullaart’s “High Retention, Slow Delivery” (2014) at Future Gallery. Courtesy of the artist.

The Dutch artist Constant Dullaart is known for a variety of conceptual projects centered around the Internet and digital technologies, many of which are relatively complex and specific to the history of computing. This one, however, is fairly simple: for $5,000, Dullaart purchased some 2.5 million fake Instagram followers, which he distributed among a group of art-world accounts (including Hans Ulrich Obrist, Ai Weiwei, Petra Cortright, and more) in an effort to “equalize” their apparent relevance. In a world that measures cultural capital by how widely your “influence” extends (or seems to extend), fake followers represent a nearly socialist attempt at wealth redistribution.

Of course, such wealth is only virtual, created, in this case, by a Lithuanian eBay contact. The question then becomes where the actual value of followers lies. In 2014, Dullaart’s gesture was often read as a commentary on the emptiness of social media striving, but, in light of the apparently pernicious role of similar “bots” in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, it takes on a more insidious tone today. In a time when social media and political reality are increasingly conflated, an army of fake online followers can indeed wield real-world power.

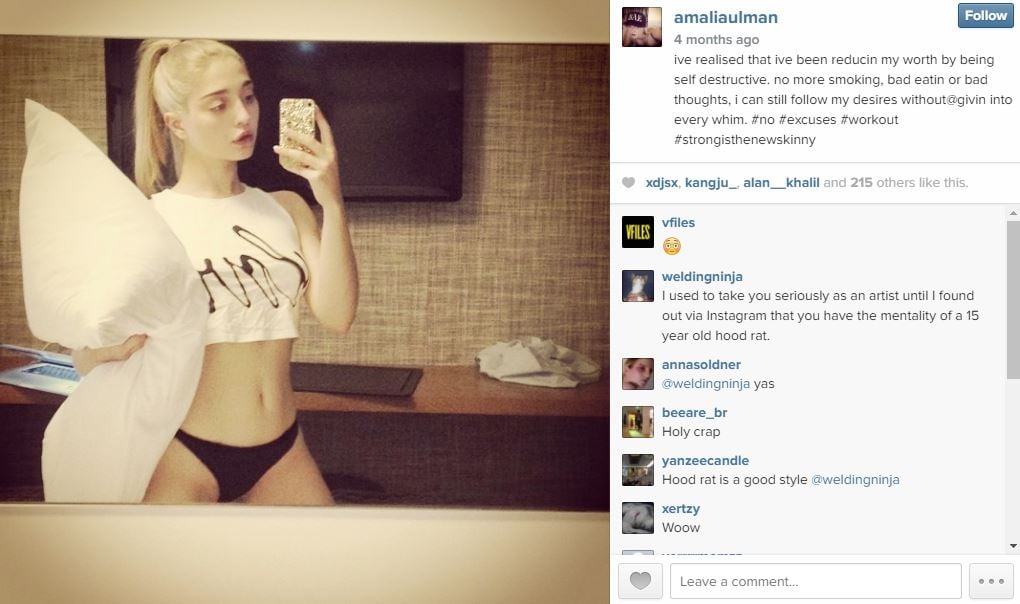

Still from Amalia Ulman’s Excellences & Perfections courtesy of Instagram.

A project that has been lauded as “the first Instagram masterpiece” by the London Telegraph, and which has earned her spots in shows from the Tate Modern to the New Museum, Amalia Ulman’s Excellences & Perfections has created a new standard for what’s possible in an online performance.

Over the course of six months in 2014, the Argentinean-born artist documented what appeared to be a personal journey of self-discovery on her Instagram profile. Narrated by her photos and captions, Ulman sets out to reinvent herself in Los Angeles, dyeing her hair blonde, adhering to a strict but trendy diet, posting aspirational cliches, flaunting apparent wealth in the form of various “hot” consumer goods, posing seductively, getting breast implants, and generally presenting herself as the archetypal Instagram It Girl. Along the way, she garnered thousands of followers, becoming one of many mini-celebs whose lifestyle and presentation online now inform the American conception of what it means to live “the good life.” The only catch: It was an act, at least partially. The plastic surgery was staged, the hashtagged bromides pre-planned (the diet and the hair dye, however, were real).

In various artist talks and statements after the fact, Ulman revealed that her real motivation was to challenge what a female artist is “supposed” to be in the current era and to point to the distance between women’s success-driven online self-presentation and the reality of their lives. Indeed, she seems to have struck a nerve: She recounts that many of her pre-Excellences art-world colleagues sought to distance themselves from what they thought was her “gaudy” new identity. One can’t help but wonder what they think now.

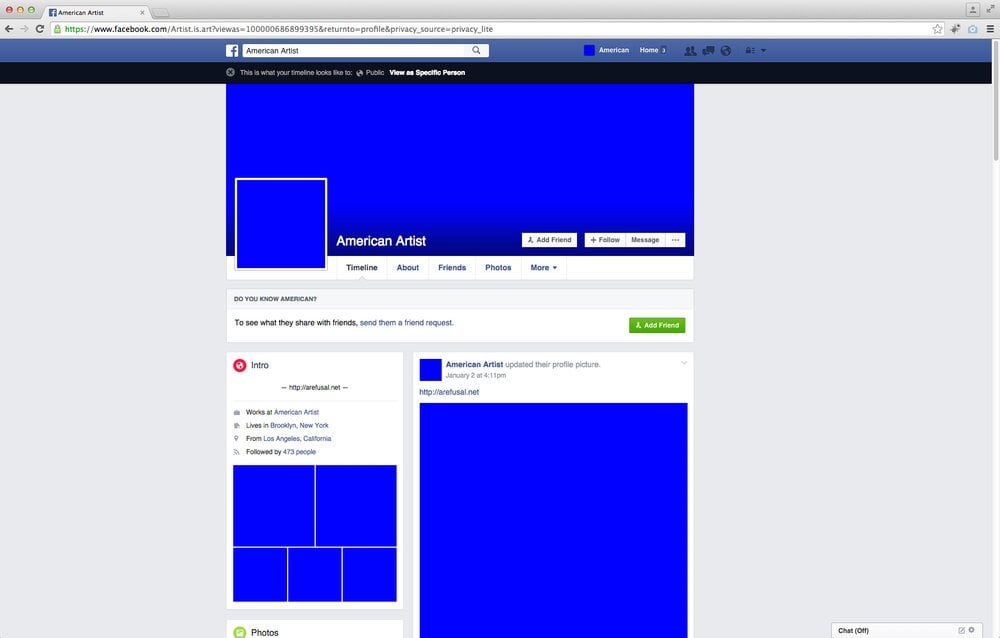

Still from American Artist’s A Refusal (2015–2016). Courtesy of the artist.

Though by design not as splashy as some of the other entries on this list, American Artist’s (yes, that’s his name) performance project is a subtle reminder of the hidden economics at the heart of supposedly “free” sites like Facebook. Over the course of a full year, Artist redacted all content he would ordinarily have posted online for his followers: Photos became rectangles in Facebook blue that are reminiscent of the Microsoft “blue screen of death,” while text posts were blacked out in the manner of classified government documents. Meanwhile, the legible content these redactions referred to was systematically archived, in physical form, for the perusal of those who made an in-person appointment to view them.

The result is a repudiation of Facebook’s basic business model, in which users provide free labor and content, paid for only in “likes,” which in turn attracts more users and, eventually, advertisers, who of course pay the platform owners (not the content creators) for the privilege of accessing their users. By opting out of this system without exiting it entirely, Artist points to a kind of cruelty at the heart of social media; as he writes in his statement on the project, the platforms offer users an experience “[a]s if the faces of those they love or admire are being dangled from a string in front of them — plainly out of reach, but close enough to keep them running on a treadmill that fuels the spectacle of society.” Think about that the next time your mom comments something embarrassing on your latest status.