Art & Exhibitions

A Major New Show Traces 200 Years of Black Artists’ Synergistic Relationship With Ancient Egypt

The Met's enthralling "Flight into Egypt" is more about reclamation than escape.

In the foyer of the Met’s second-floor gallery, Cleopatra’s Chair sits empty, beckoning. This throne, constructed by legendary sculptor Barbara Chase-Riboud, is a remnant of a sustained revelation. In 1957, at only 18 years old, the American artist visited Egypt and experienced an awakening, this first encounter with artworks beyond the European canon influencing her practice for decades. She recalled of the experience: “For someone exposed only to the Greco-Roman tradition, it was a revelation. I suddenly saw how insular the Western World was vis-a-vis the nonwhite, non-Christian world. The blast of Egyptian culture was irresistible. The sheer magnificence of it. The elegance and perfection, the timelessness, the depth. After that, Greek and Roman Art looked like pastry to me.” She completed Cleopatra’s Chair in 1994 (five years before her own groundbreaking solo exhibition at the Met).

“Flight Into Egypt: Black Artists and Ancient Egypt 1876–Now” highlights almost 200 years of this return-to-self. It’s a meeting ground of Black cultural production, a decidedly pan-African sensibility that engages with ancient Egypt as a spiritual point of reference for fashioning a collective identity; a source for inspiration and a site of affinity against the erasure of a cultural lineage. The exhibition, on view through February 17, 25, offers more than mythos, grounding itself in the promise of great origins reclaimed from a discipline of Egyptology that had categorized the civilization as “proto-European,” separate from the rest of continental Africa. The show’s aims are clear, but our means of flight remain as unresolved as these histories. Egyptian sphinxes don’t have wings.

Installation view of “Flight into Egypt: Black Artists and Ancient Egypt, 1876–Now,” on view November 17, 2024–February 17, 2025 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Eileen Travell, Courtesy of The Met

The Met’s warm walls bear the threads of this restorative practice with a nod of recognition. It’s a noteworthy celebration that feels uncharacteristic—if not unheard of—at this institutional scale. The museum’s commitment to the work feels singular in its candor, an endeavor that imbues the space with an authenticity that is above all else deeply comforting. It’s a feeling only dwarfed by the magnitude of its implications: the way a movement appears before our eyes with resonances that touch the soul.

The survey’s pantheon of Black artists ranges from contemporary titans like David Hammons and Jean-Michel Basquiat to lesser known figures from the 19th century. Together they depict a well of spiritual data, the source material of self. Beyond the visual works, however, the abundance of music and literature underscores the museum’s role as a public resource.

Installation view of “Flight into Egypt: Black Artists and Ancient Egypt, 1876–Now,” on view November 17, 2024–February 17, 2025 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Eileen Travell, Courtesy of The Met

In the room titled “Awakening and Ascent,” covers of early issues of The Crisis, a magazine published by the NAACP since 1910, are just one element exploring Afrocentrism’s rise alongside the moods of the Harlem Renaissance. Copies of the publication, alongside other corollary publications, are available to peruse in a spacious reading room designed by Steffani Jemison and Jamal Cyrus. The exhibit’s final room “Space Is The Place” carries the name of the canonical film featuring Sun Ra. Alongside other images rife with pastiche, the videos are just one of many instances where the show complicates the work of dreaming up Black futures. The exhibition is an accessible anthology; the stories bound to each piece are at once preserved behind vitrines and within arm’s reach.

In the “Kings and Queens” section, Fred Wilson’s Grey Area (Brown Version) greets the viewer: a series of five bust-replicas depicting Queen Nefertiti, their plaster pigmented in shades ranging from sandstone to deep umber. The series contends with the question of color, its lingering influences on our contemporary perceptions of these ancient histories. With enough time, the eye discerns that none of the busts’ shades resemble human skin. The busts only acknowledge the impossibility of their resemblance to any common reality. There remains an ever-expanding spectrum of colors between these figures, unsettled explorations of a contested history.

Still from Space is the Place (1974). Directed by John Coney. Courtesy North American Star System Production; John Coney

On the other side of the wall, a series of diptychs by conceptual artist Lorraine O’Grady likens photographs of her sisters and daughters to the remnants of royal Egyptian stoneworks. Her late sister, Devonia Evangeline O’Grady, appears in a bridal portrait beside a photograph of the renowned Nefertiti bust referenced by Wilson (as well as a critical mass of other artists featured in the show). In the series, titled Miscegenated Family Album, O’Grady highlights the widely understood cultural and gendered associations around figures such as Nefertiti, echoing the ways in which a shared ancestry continues to both unify and trouble our own legacies. An image of the queen’s bust sits on my bedside table.

Installation view of “Flight into Egypt: Black Artists and Ancient Egypt, 1876–Now,” on view November 17, 2024–February 17, 2025 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Eileen Travell, Courtesy of The Met

The collection of works in the show together highlight Egypt’s long-held sacred presence in our dreams: something to strive for and somewhere we’ve already been. The works stand in as tools against social death, a record of the imaginative thinking required to transcend what has marred Black identities across the globe for generations.

Nearby, Simone Leigh’s contemplative bronze figure, Sharifa, leans against a wall. The figure towers in the room at a stature over nine feet tall, even in repose. One foot emerges from under her floor-length dress, implying something of the precarity of her posture, or perhaps footnoting the fine line between rest and labor under the contingencies of Black feminine embodiment. While there are pieces by Leigh more directly emblematic of Egypt’s influence on her practice—such as the glazed Sphinx she featured at the 2022 Venice Biennale—this monumental work shares the massive quality of an obelisk, a presence felt by way of its indifferent gaze. It’s an association further heightened by two adjacent gypsum totems by LA-based sculptor Lauren Halsey, constructed specifically for the show. The pair of untitled works are airbrushed with landmarks from the artist’s hometown, both those recognized by the city and those sanctified by its residents. These are monuments to the intimately local, shaded by the motifs of a history that edges on mythology.

Installation view of “Flight into Egypt: Black Artists and Ancient Egypt, 1876–Now,” on view November 17, 2024–February 17, 2025 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Eileen Travell, Courtesy of The Met

The section of the show titled “Nu Nile Abstraction” presented some of the most formally risky works in the show, examples of how the glance-friendly symbologies that fill other rooms can be distilled to pure concept. Here, many artists take on the shifting image of the pyramid as a point of departure. Maren Hassinger’s Love (Pyramid) forms its triangle shape in the gallery’s corner. Pinned to the walls and floor, each pink plastic bag is filled with human breath, an accumulation of utterances – the word love. Rashid Johnson’s sculptural environment, titled Pyramid, offers objects rich with cultural memory atop its shelves: mounds of shea butter and black soap, a vinyl record from The Modern Jazz Quartet. The sentimental takes form through the readymade. At the center of the space, Sam Gilliam’s Pyramid refurbishes the sacred geometry in lacquered wood, providing a launchpad for the psychic leaps that make these worlds coterminous with the contemporary.

Clips of music videos and performances by Alice Coltrane, Michael Jackson, and Beyoncé ground the exhibition in cultural touchstones accessible for a wide audience. Played in sequence, they begin to map a cycle of reincarnation among these pop culture icons, though the pharaonic archetypes they reference remain timeless. The well-known video works are staged in a screening room outfitted with a disco ball in the shape of our dear Nefertiti. This multimedia approach doesn’t end with the objects on display. A robust performance program is set for the specially-built neon atrium dubbed “The Performance Pyramid.” The space will host artists such as Karon Davis, Clifford Owens, and M. Lamar & The Living Earth Show, in collaboration with Met Live Arts. Tomassino hopes the exhibition can be a “welcoming cultural oasis for people of all walks of life.”

Henry Ossawa Tanner, Flight Into Egypt (1923). Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, image © Metropolitan Museum of Art

While there are many allusions to ancient architectures and traditions of object-making throughout “Flight,” the curatorial team resisted including any antiquities from the Met’s collection. McClain Groff, the Research Associate for the exhibition, tells me that this noted absence is intentional. “If you want to see those, you can go to the Egyptian wing.”

“Flight into Egypt,” does, however, include the works of living Egyptian artists such as Cairo-born sculptor Iman Issa and feminist polymath Ghada Amer. The “Heritage Studies” on display are more in conversation with each other than they are with any preoccupation with the “ancient.” Maha Maamoun’s Domestic Tourism II is a montage steeped in celluloid fantasy, a compilation of popular cinematic representations of Egypt from the New Hollywood era of the mid-20th century. Mahmoud Mokhtar’s Bride of the Nile rests in the center of a room, a subtle standout among more commanding figurative works. The bronze and silver bust peers over its scarab-encrusted clavicle, as if eavesdropping on the video collage installed behind it. She personifies the collective turning of a head to look back on a past that is never as distant as history may portray. Her earring dangles, frozen in an inertia that is almost audible.

Moving through the show there’s a sense of the perennial now-ness of Egypt’s influence. Everyone has their own relationship to the mythology; there was a feeling of nostalgic pride visible on the faces of many wanderers. For curator Akili Tommasino it’s especially personal: “I designed [the exhibition] for myself at 15.”

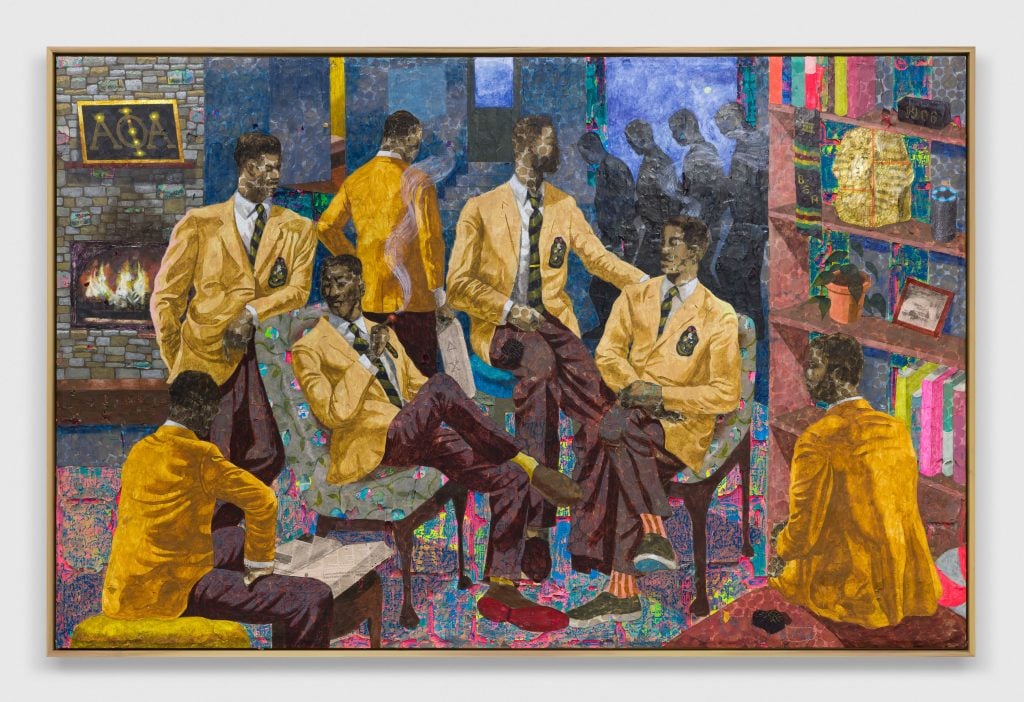

Derek Fordjour, Board Meeting (Brotherhood Smoke) (2021). Collection of Robert F. Smith Photo: © Derek Fordjour, courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Photo: Mark Blower, Daneil Greer

As a child of immigrants hailing from the island nation of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Tommasino’s upbringing in Brooklyn influenced his own understanding of a larger, global African diaspora. This experience is common, a way to reconcile, a rite of passage. The urban environment continues to inspire. Three longstanding public artworks located in Harlem are temporarily designated as part of the exhibition. The inclusion of these site-specific works, located in subway stations and along the Metro North railway, highlights the populist essence of this pan-African sensibility. It’s a coveted tradition, one that has been deployed thoroughly across disciplines for over a century, but has never been concisely articulated with such focus until now.

The tradition, however, appears to be so pervasive that it also at times veers into cliché. These gestures of self-appropriation are often derided when pushed up against newer schemas of Black liberation. A pride in Egyptian ancestry among Black Americans has often been relegated to an association with the “hotep,” a term referring to a derogatory archetype of Black pride that has come to resemble a parody of the aesthetics on display in the Met show.

Installation view of “Flight into Egypt: Black Artists and Ancient Egypt, 1876–Now,” on view November 17, 2024–February 17, 2025 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Eileen Travell, Courtesy of The Met

I asked Tommasino about potential associations with the label “hotep,” and he led me to the work of Kemetic practitioner and jeweler Baaba Heru. My eyes were drawn to The Ankh of Love, a hand-forged and -filed talisman composed of copper, silver, and brass in the shape of the symbol for eternal life. My mother’s only tattoo is an ankh. Her name is Love. “Heru said that when he got into Kemetic studies, saying ‘hotep’ was a way to greet each other with peace,” Tommasino explained, adding that he hopes this exhibition “helps resuscitate some of the original spirit of the greeting of peace.”

What we’re left with is a tradition still in-progress. As a counter to the storied conditions of our social realities, such cooptation proves essential to our own perpetuity. In communicating the countless ways in which Black artists lay claim to these symbols as artifacts of ourselves, the exhibition offers a look at their nuanced circulation through a third eye.

“Flight into Egypt” is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art until February 17, 2025.