On View

A New Survey of Black Portraiture Rewrites the Art Historical Canon

The survey spotlights celebrated artists like Kerry James Marshall, Amy Sherald, and Michael Armitage.

The survey spotlights celebrated artists like Kerry James Marshall, Amy Sherald, and Michael Armitage.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

Since the very earliest art forms, artists have been compelled to depict the human figure. These images allow us to see ourselves, our societies, and our cultures reflected back and recorded for posterity. “The Time is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black figure” is a new survey at the National Portrait Gallery in London that considers how 22 artists from the African Diaspora are currently choosing to reflect the Black experience.

Some of the biggest names on show include Kerry James Marshall, Amy Sherald, Michael Armitage, and Lubaina Himid, and all of the works were completed at some point in the past two decades. The exhibition was initiated by Ekow Eshun, the writer, broadcaster, and curator behind the Hayward Gallery’s hit show “In the Black Fantastic” in 2022.

At the “The Time is Always Now” opening, Eshun explained that the exhibition’s title comes from “an awareness that we’re in an extraordinary moment right now, a moment of flourishing when it comes to work by contemporary artists from the African Diaspora working in figuration.”

“These works are thinking about a history of being overlooked, misrepresented, or depicted without agency,” he added. “These works are not a rectifier of that, per se. These artists are simply commanding space on their own terms.”

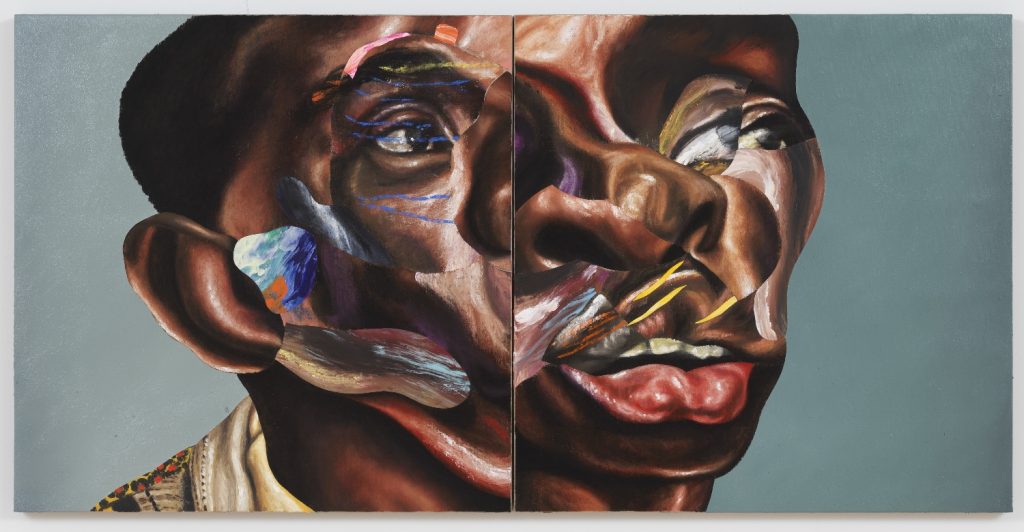

Nathaniel Mary Quinn, Father Stretch My Hands (2021). Photo: Rob McKeever, courtesy of Gagosian.

The show’s first of three themes, “Double Consciousness,” borrows its title from the great thinker W.E.B. Du Bois, who used the term in 1897 to encapsulate the Black experience of living within a white society but also outside, psychologically speaking.

“It is a peculiar sensation, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others,” Du Bois once remarked. If this feeling can be translated to canvas, it might resemble the fragmented portraits of Nathaniel Mary Quinn, which remind us that our perceptions of the world around us are never static or entirely coherent. His beguiling works are among the best on show.

Claudette Johnson, Standing Figure with African Masks (2018). Photo: Andy Keate, courtesy of the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London.

Out of a handful of sensitive and warm character studies, Jennifer Packer’s intimate portraits of family and friends attract the eye for how her painterly apparitions appear to almost melt or drip away. Claudette Johnson’s Standing Figure with African Masks (2018) offers a fun twist on one of the defining images of the avant-garde, Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). Johnson takes the West African Dan masks Picasso appropriated in his seminal 20th century painting and reclaims them as the backdrop for an assertive image of herself that she had originally planned to name Brazen Woman. By the entrance, gleaming under the gallery lights, is a towering gold monument to the Black figure, a young woman in sportswear by Thomas J. Price.

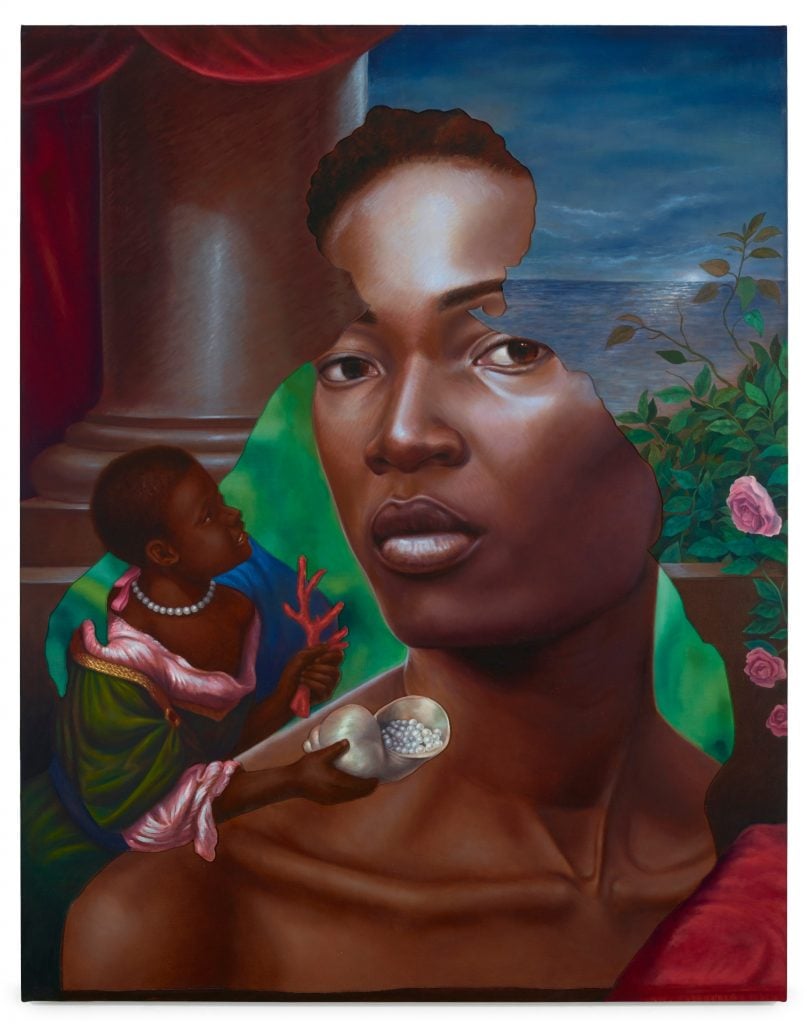

Titus Kaphar, Seeing Through Time 2 (2018). Photo: Christopher Gardner, courtesy of the artist and Gagosian.

The white gaze that has dominated so much of the art historical canon is sidelined in a series of galleries dedicated to the theme “Persistence of History.” Titus Kaphar takes to task a staple portrait set-up from the colonial era, that of a Black boy attending to a white female sitter. In his standout work Seeing Through Time 2, the central subject of Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth is removed and the boy instead kneels in reverence to a Black figure who fills the empty silhouette.

Barbara Walker’s drawings similarly foreground the Black servants or enslaved people that had been historically relegated to the status of background figures, filling them in with graphite while those who were once considered to be the composition’s obvious subjects are merely suggested by an embossed outline.

Jordan Casteel, Yvonne and James (2017). Photo: Adam Reich, courtesy the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York.

Finally, the theme of “Our Aliveness” unites works by artists like Toyin Ojih Odutola, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, and Henry Taylor, that display a sense of contemporary community. Jordan Casteel places the spotlight on everyday, easily overlooked passengers riding the New York City subway; in this case the sitters are James, who sells vintage vinyl records, and his friend Sylvia, who runs a soul food restaurant in Harlem. Meanwhile, Hurvin Anderson’s colorful yet subtly understated paintings center the barbershop as a site of kinship for people of Caribbean origin in Britain.

Denzil Forrester, Itchin & Scratchin (2019). Photo: Mark Blower, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery.

The exuberance of a crowd that fills a dimly lit but lively reggae dancehall in London in the 1980s practically leaps off the canvas in a work by Denzil Forrester. Opposite, the dense layering of imagery in Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens (2021) is masterfully achieved so as to never detract from the principal composition. A self-portrait of the artist with her child, the work is immediately striking long before the viewer steps closer and drinks in the intricate patterns and archival photographs imprinted onto the scene’s lush foliage.

“The Time is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure” is on view at the National Portrait Gallery in London through May 19, 2024.