On View

Artist Kerry James Marshall’s First Commissioned Portrait Captures the Quiet Authority of Renowned Scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Marshall has donated the painting to Cambridge University.

Marshall has donated the painting to Cambridge University.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

American artist Kerry James Marshall has produced his first-ever formal portrait, choosing to depict the renowned African American scholar and historian Henry Louis Gates, Jr., often known as Skip. The work has been donated to Gates’s alma mater, the University of Cambridge, and is now on public view at Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum.

The gift is a major coup for the regional museum—becoming only the second painting by Marshall to enter one of the U.K.’s public collections. Celebrated for his typically lively scenes in which Black people enjoy everyday pleasures like a backyard barbecue, a trip to the hair salon, or a day spent by the river, Marshall recently became the most expensive living Black artist.

Gates, a Harvard professor of African American studies and a prolific writer, met up with Marshall at the Fitzwilliam earlier this week to unveil the work. The pair, whose long-time admiration of each other has formed the basis for a fond friendship, were in a jocular mood as they recalled the circumstances that led up to the portrait.

Shortly after majoring in History summa cum laude at Yale in 1973, Gates was the first African American to receive a fellowship to study abroad from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Though he had been “raised to be a doctor,” he enrolled in English Literature at Clare College, Cambridge, eventually finding a passion for African and African American literature thanks to the mentorship of Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka. “I owe this place quite a lot,” he said, reflecting on the encouragement he received to pursue academia. “I feel indebted.”

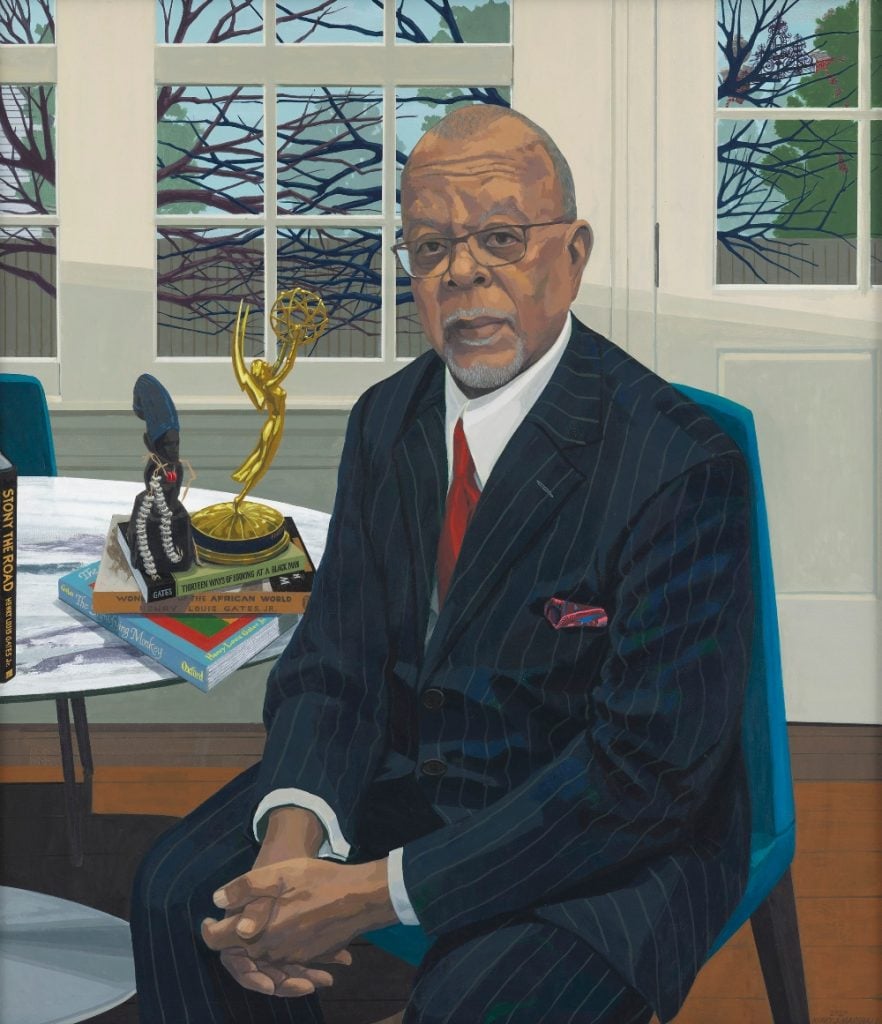

Kerry James Marshall, Henry Louis Gates Jr (2020). Photo courtesy of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

Nearly 50 years later, in 2020, the university offered Gates an honorary degree. The scholar offered to commission his own portrait for the college’s graduate common room, calling up his friend Marshall for a favor. Despite never having worked on a formal portrait, he “agreed right away,” and the painting was swiftly allocated to the Fitzwilliam instead. “Once they realized this was a Kerry James Marshall work of art, it could not be in a common room with a bunch of students spilling beer all over it,” joked Gates.

“It was a no brainer. This was not something you could say no to,” said Marshall. “Skip Gates is the W.E.B. DuBois of my generation. These are the people who made being a public intellectual something achievable.”

The sensitive portrayal of Gates shows him seated in an office, turning away from a pile of his own books to face the viewer. “I was interested in painting a picture that had a certain presence that gave Skip the authority he deserved for the stature he has achieved,” said Marshall.

And what of Marshall’s precedent for avoiding portraiture? “Of course, it’s not because I can’t,” he said. “I’ve been invested in making art that is based on ideas, art as a philosophical pursuit. And I make images of people who have a presence in history of which there are no images.”

“The reason I paint figures black is because the Black figure operates as a rhetorical figure,” said Marshall, referring to the unmixed, unadulterated shades of black that he uses for skin tones. “It’s always been stated that black is not a color and you should never use the black that comes out of a tube, but those blacks have a chromatic reality too,” he explained. “My mission was to make those black figures become as chromatic as every other color in the painting. Black is being treated as if it’s a complex color too.”

The shift to portraiture required a slightly different approach. “When it comes to making a painting of Skip, he did ask me, ‘what color am I gonna be?'” recalled Marshall with a laugh, to which Gates exclaimed, “I wanted to be black!”

“I didn’t do that, because to change people… to misrepresent somebody as a color they are not, is akin to blackface,” said Marshall, adding that he decided to make the portrait more true-to-life with naturalistic skin tones.

The pair also used the painting as a starting point to talk more generally about how race relations have changed in the U.S. over the course of their lifetimes. Gates spoke out against the Supreme Court’s recent 6-3 vote to reverse affirmative action, which was introduced in the 1960s. “I wouldn’t have gotten in to Yale without affirmative action,” he said. “The class of 1966 had six Black men graduating, the class that entered Yale with me in 1969 had 96 Black students, and we went on to integrate the power elite. Since 1970, the Black middle class has doubled.”

“The right is trying to end all that,” Gates added. “They’re saying, I don’t know how Kerry James Marshall is in the Met, and now the Fitzwilliam, but that’s over. They are in panic because they saw too much power, too quickly for Black people and they’re trying to roll back the clock.”

“All these things are possible,” said Marshall. “They were possible for [Gates], they’ve been possible for me. I don’t see how they are not possible for anybody who doesn’t take the opportunity and do the work that’s required. That’s how I see the world,” he added. “And in terms of progress that needs to be made, because of the position I have now, I’ve been able to dramatically change the lives of a lot of people. That’s all I can do so that’s where I focus my attention.”

More Trending Stories: