This year’s Venice Biennale, curated by Hayward Gallery director Ralph Rugoff, certainly lives up to its title “May You Live in Interesting Times.” Mapping out contemporary concerns tastefully, judiciously, but nonetheless with an unmistakable urgency, the show’s artworks regularly hit a few key themes: existential terror about the future of our warming planet, alarm in the face of inexorably advancing technologies (robots, AI, deep fakes), excitement about increasingly fluid modes of identity, and, thrumming as a base note throughout the proceedings, an understanding that historical wounds inflicted by West’s colonial past remain un-sutured, raw, and festering.

Nowhere is this last theme more searingly expressed than in Arthur Jafa’s White Album, a 40-minute 2018 video montage of white people addressing or embodying—in mortifying, illuminating, or horrifying ways—American racism.

Arthur Jafa, The White Album (2018). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Jafa’s video, which was awarded this year’s Golden Lion for best contribution to the main exhibition, leaves the viewer awed and decidedly not optimistic about the direction of America. (At one point, the film excerpts an extended monologue from YouTube pundit and self-described former racist “redneck” Dixon White, who says, “let’s face it, white supremacy is real… entertainment is whitewashed and biased… our white culture is racist.” His position becomes more complicated when his explains the underlying point of his truth-telling: “White people have to change our culture of white supremacy. If we don’t they will destroy us all.”)

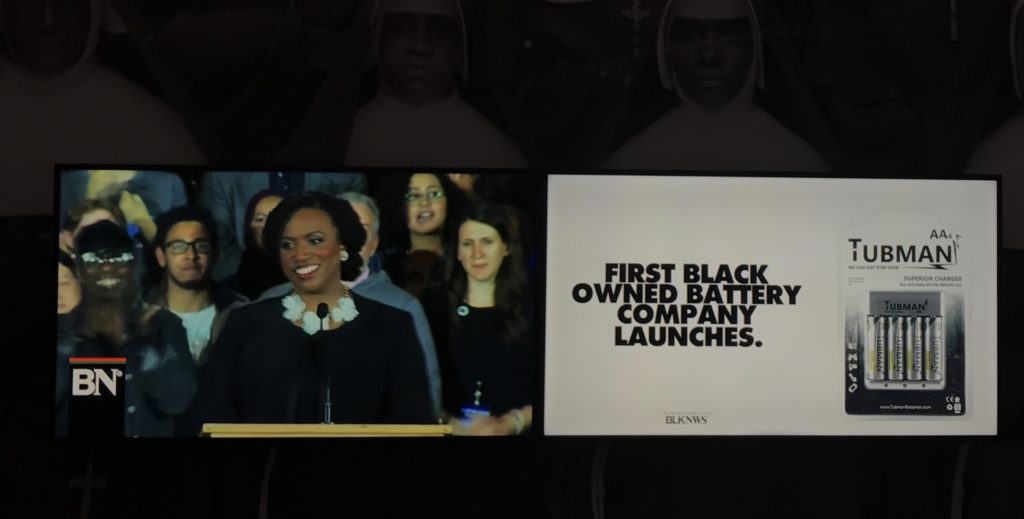

But if Jafa’s video is a diagnosis, another video work at in the Biennale is—in a way rarely encountered in an art show—something like a prescription. Kahlil Joseph’s BLKNWS offers a kind of yin to Jafa’s yang: a moving, funny, and aspirational vision of what media might look like if it were not, as White says, “whitewashed and biased,” and rather more creative and reflective of the world we live in and the history that shaped it.

The only work that is shown in the same form (with different backdrops) in both the Giardini and the Arsenale, BLKNWS is a two-channel video that imagines a cable news network animated by a cosmopolitan, culturally omnivorous, politically engaged, art-loving, and intellectual black sensibility—a bit like if BET merged with CNN and then merged with Artforum and the New Yorker. While it is presented as an uninterrupted flow of images, clips, segments, and pop music in a way that gives it an associative artistic quality—and echoes the video style made famous by Jafa, a mentor and friend of Joseph’s who name-checked him in his Golden Lion speech—it was actually originally created as a pitch to cable networks for a real-life news show. Because all the major networks turned down the idea, it now exists in the Biennial as the evocation of a counter-factual creative vision, i.e. an artwork.

Those networks should give it another look, because BLKNWS shouldn’t be art. It should be real.

The notion that an artwork could transform into a massive media conglomerate isn’t unprecedented. Remember that Buzzfeed started as an art project. BLKNWS is also informed by the black-founded publications and media organizations that came before it, including the Johnson Publishing Company’s Jet and Ebony magazines and, of course, BET, which could be seen as a BLKNWS for an earlier era (its own TV news program, BET Nightly News, stopped airing in 2005 after a four-year run). But there are three elements that make Joseph’s project different from these, and make it primed to resonate with the moment.

For one thing, in a saturated media environment where people are trying to edit down their consumption, news breaks through—it is essential, with real utility, rather than simply recreational. For another thing, more than ever, black culture is world culture. A staggering array of the most exciting, vanguard-probing work being done in art, music, film, television, literature, sports, politics, and intellectual discourse is being generated in and out of the context of black culture. It is, increasingly, youth culture. Art, meanwhile, is ever more central to popular conceptions of the fulfilled good life.

The final element that works in BLKNWS‘s favor is that it’s necessary.

Kahlil Joseph’s BLKNWS, 2019. Photo by Andrew Goldstein.

Media Matters

Before going further into what BLKNWS is, I’d like to first ground this review (if that’s what it is) as coming from the perspective of the editor-in-chief of an online art news site in the year 2019. Today, with so many pipelines of information constantly streaming news and commentary from all manner of sources, journalism largely consists of two key activities: story choice and angling. Both of these actions stem naturally from what legendary New York magazine founder Clay Felker identified as the beating heart of a media outlet: its POV, or point of view. That’s why, in today’s media environment, the New York Times can break a story and then another publication can instantly pick up elements of that story, re-angle it through its own POV, and meaningful serve them to its own audience.

Now, because the business models for almost all media outlets depend on audience numbers, editors are incentivized to guide their story choice and angling based on what resonates the most reliably with their target demographic. As a (white) editor who pays attention to audience engagement, I can confirm something that won’t surprise any close watcher of the news: nothing is more reliable in terms of generating audience engagement than turning out variations on popular narratives that recur, and can be retold, again and again.

Foxnews.com, for instance, loves stories about attractive high-school teachers going to jail for sleeping with their students; People.com loves awful things happening to families, famous and non-famous alike; VanityFair.com loves telling its readers that some infinitesimal new revelation is sure to sink Donald Trump for good. People are crazy for being told stories that, as variations on a well-worn theme, confirm their already-held view of the world. They can tut-tut, ignore any inconvenient detail that doesn’t chime with what they believe to be true, and continue contentedly on their way.

Kahlil Joseph’s BLKNWS, 2019. Photo by Andrew Goldstein.

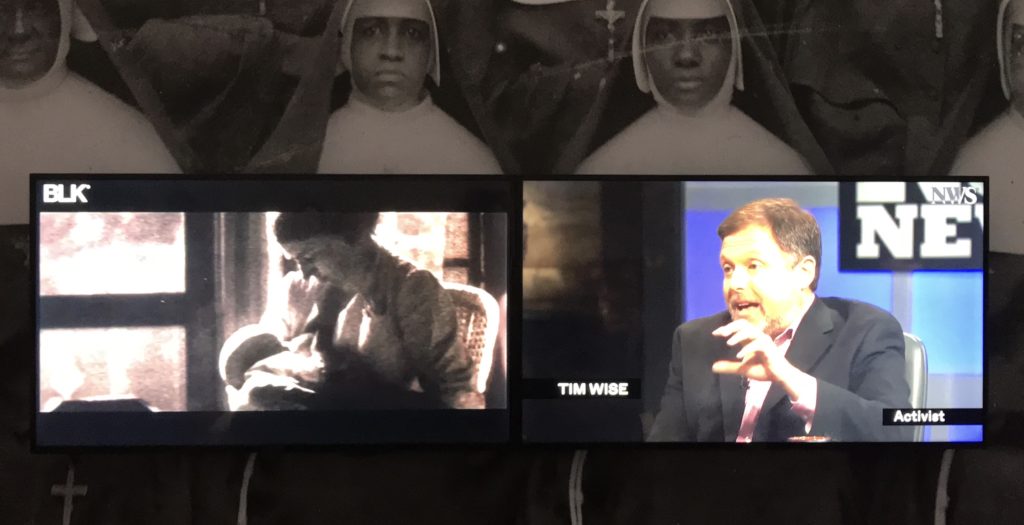

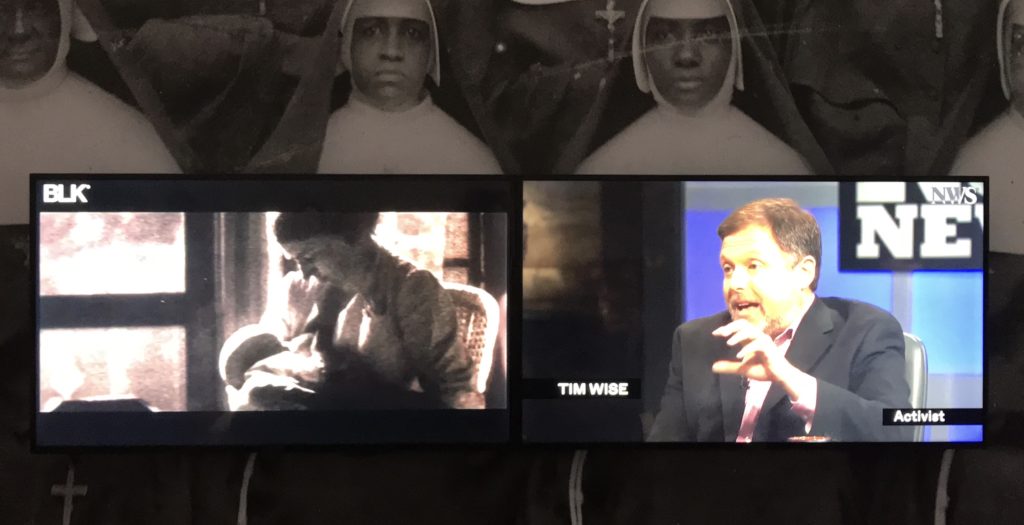

That’s why in today’s media landscape, you often get a lot of narratives that present stories about black people filtered through a dominantly white perspective—which is immensely pernicious in a country like America where tests have shown that even “liberal white people,” as the anti-racism activist Tim Wise says in a BLKNWS segment, “internalize biases” to the extent that if they are shown an image of black people for even just 85 milliseconds the “part of the brain that reacts to fear and anxiety [lights] up like a Christmas tree.” In other words, you get a lot of narratives about black violence and also well-trod leitmotifs like sports excellence, hip-hop excesses, and problematic parenting. Anyone, when exposed to such a paucity of story-lines, of depicted modes of identity, runs the risk of, to paraphrase a clip of Maya Angelou from BLKNWS, “believ[ing] their own publicity.”

As, again, a white editor, I am keenly aware that I may be a flawed messenger to weigh in on the vision behind BLKNWS—in a sense, I run the risk of becoming another voice in Jafa’s White Album. But I am also keenly aware that Joseph’s black-POV news network would help bring about a necessary course correction. A filmmaker and artist who has also made music videos for Beyoncé and Kendrick Lamar, Joseph has become known, in the words of New Yorker critic Hilton Als, as the “the creator of intellectually and emotionally dense short films showcasing black excellence, strangeness, and history.” BLKNWS, as would follow, is a pitch for a media outlet attuned to “black excellence, strangeness, and history.”

What would that look like? There are a variety of components in BLKNWS that, taken together, map out the terrain of a clear editorial sensibility.

Kahlil Joseph’s BLKNWS, 2019. Photo by Andrew Goldstein.

A Look Into the Future?

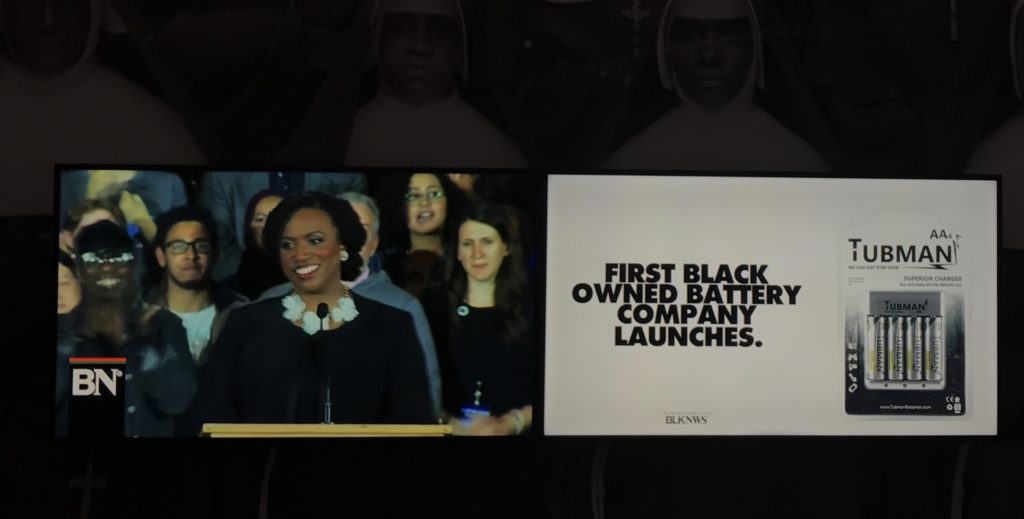

First, there are the requisite anchors and assorted cable-news-style talking heads who preside over segments, from former MOCA curator Helen Molesworth and Alzo Slade (a current VICE News Tonight correspondent) discussing a study that finds gang members are at high risk of PTSD to Slade and Amandla Stenberg (a young actress made famous as Rue in The Hunger Games) enthusiastically delivering local election coverage. (“More women are running and being elected to office,” they say from behind a polished desk. “One of these women is Mariah Parker, a rapper, PhD student, and now newly elected county commissioner of Athens, Georgia…. With an afro reminiscent of Angela Davis, Mariah Parker was sworn with one hand on the Autobiography of Malcolm X … and the other was a raised fist in the air.”)

Kahlil Joseph’s BLKNWS, 2019. Photo by Andrew Goldstein.

Then there are clips—both original and found—of leading intellectuals talking about the pressing challenges and empowering ideas of the day, from climate change to black identity and self-determination. (The poet and theorist Fred Moten ponders, “What would a life be that wasn’t interested in leaving a trace of human habitation?”)

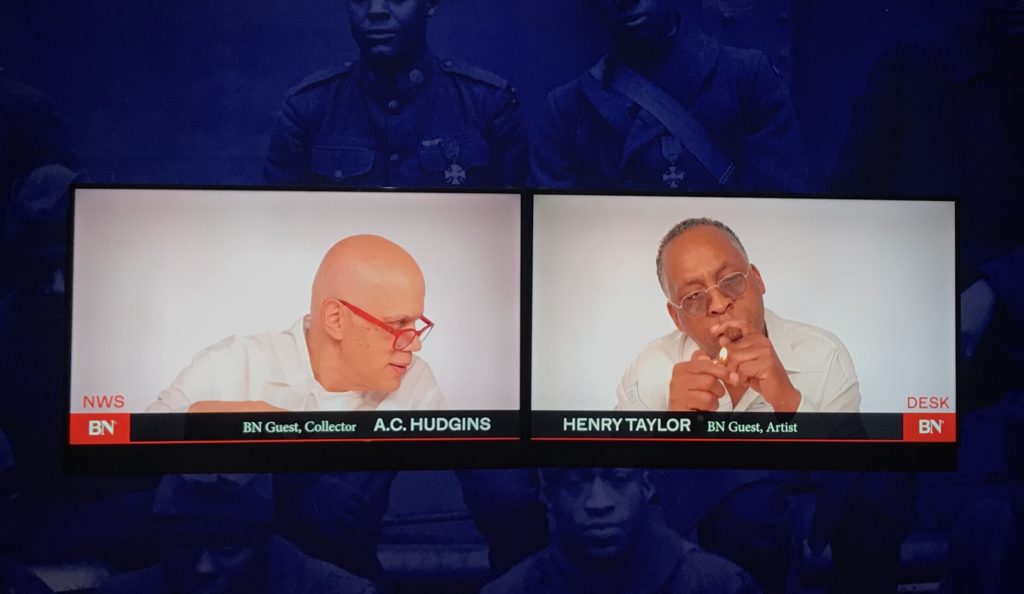

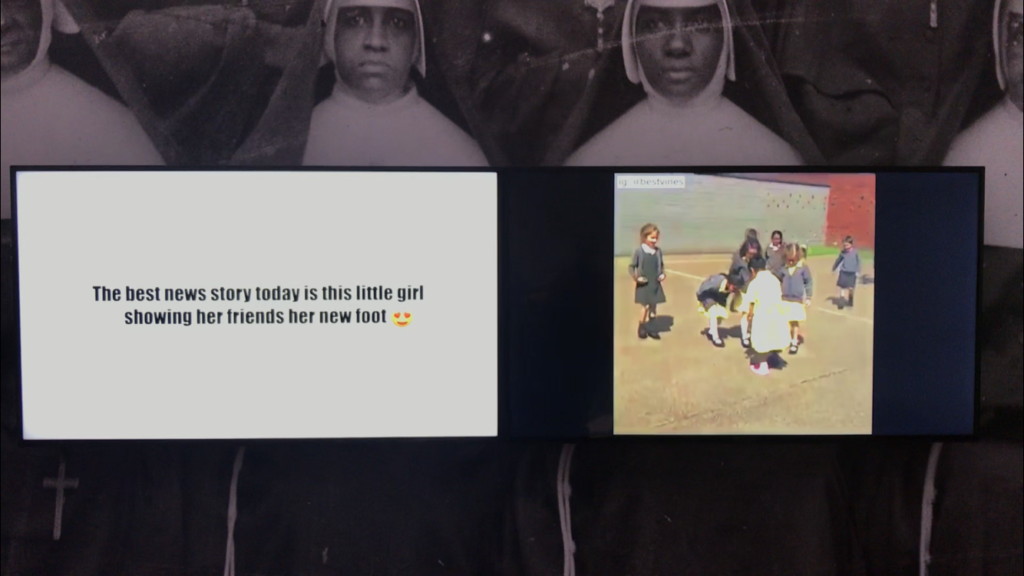

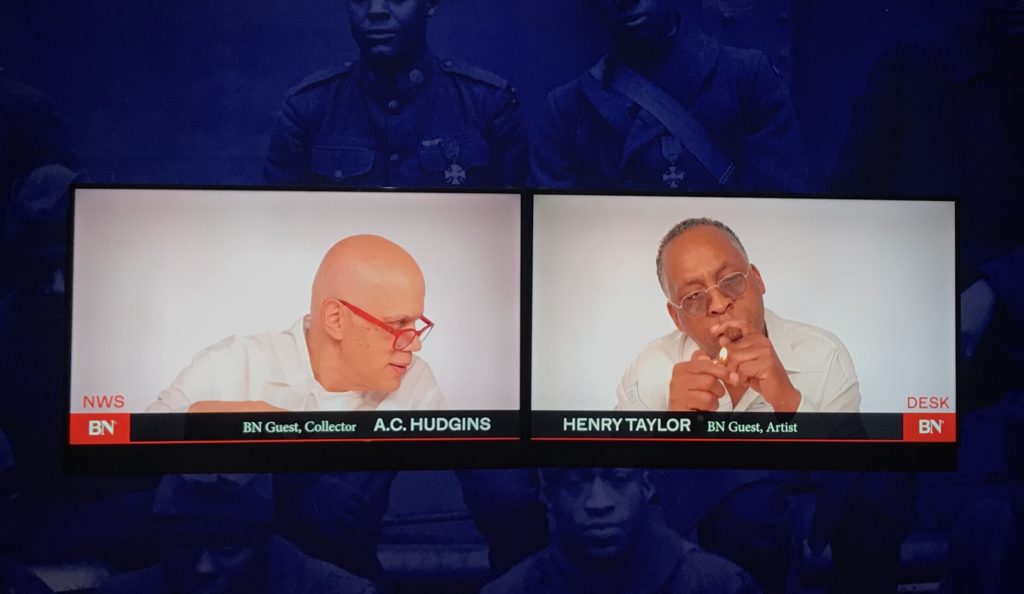

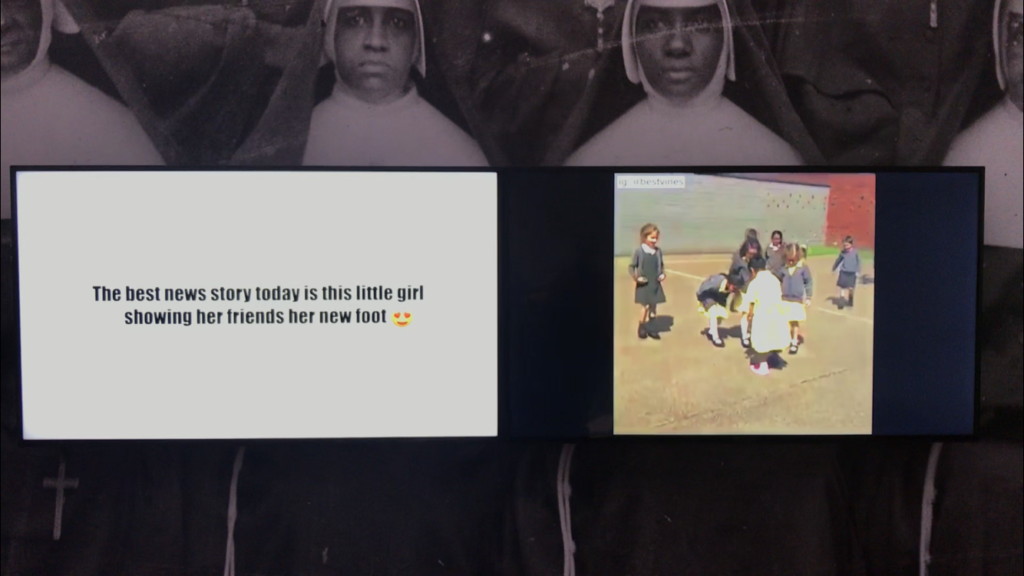

Other segments offer a glimpse of fruitful potential programming directions. In a quirky spin on the old “Crossfire”-style two-person conversation show, the collector and MoMA patron A.C. Hudgins chats with the painter Henry Taylor. In a social-media-derived “spot,” the text “the best news story today is this little girl showing her friends her new foot ?” is displayed alongside footage of a child with a prosthetic limb getting hugged on the playground.

There’s also room for stand-up: In one clip, the comedian Michael Che does a riff on why he can’t understand the opposition to Black Lives Matter (“We can’t even agree on Black Lives Matter. Not more than you. Just matter”).

Kahlil Joseph’s BLKNWS, 2019. Photo by Andrew Goldstein.

The most avant-garde part of BLK NWS may be the fact that, interspersed between these snippets of programming are an impressionistic flurry of decontextualized clips and images of uplifting, inspirational scenes from black American life—a kind of slowed-down obverse of the subliminal messaging touched on by activist Tim Wise (and which Joseph underscores with a clip of flickering-image brainwashing from The Parallax View). A woman cries when she opens a surprise engagement-ring box; a father gives his young daughter a bath; a woman in a martial-arts class subdues a would-be assailant; skaters scoot around a roller rink. All is infused with the positivity of a Facebook or Nike ad; at one point, we see part of an actual Nike ad.

Kahlil Joseph’s BLKNWS, 2019. Photo by Andrew Goldstein.

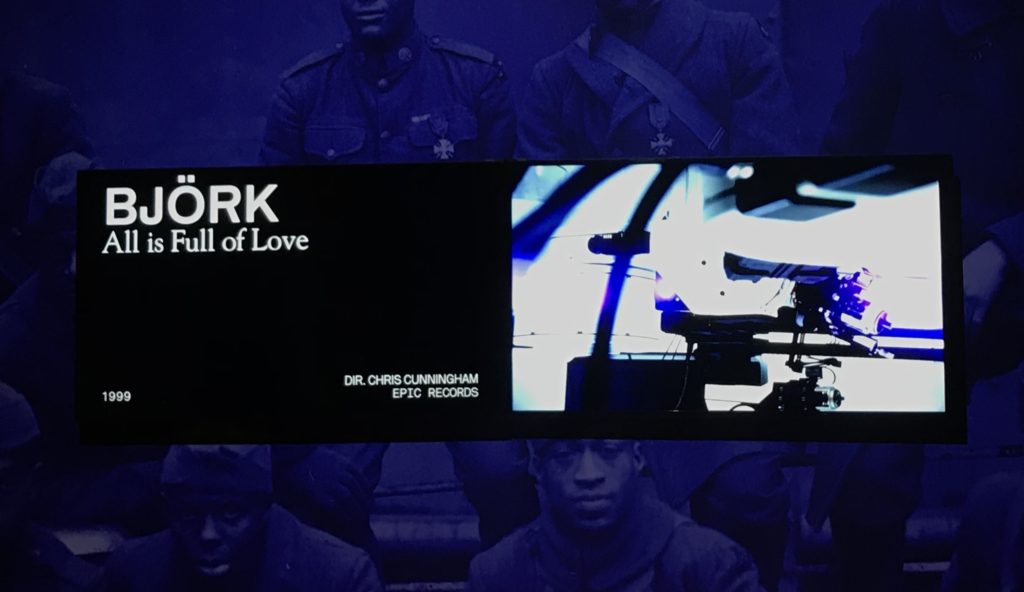

Other times, the BLKNWS logo is shown superimposed on clips from Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away, the kissing female robots in the video for Björk’s “All Is Full of Love,” a CGI animation of a dinosaur running through its fiery meteor-borne apocalypse, a photo of the police-slain teen Michael Brown. The message is clear: this is an encompassing, global, unlimited POV. I mean, who wouldn’t watch this?

Kahlil Joseph’s BLKNWS, 2019. Photo by Andrew Goldstein.

A Step in the Right Direction

Occupying, as it does, a funny position between an artwork and a pitch for actual TV programming, BLKNWS is tricky to pin down. Is it a proposal? A critique? A mix of both? Some light might be shed here by the example of the Underground Museum, the near-mythic art space that Joseph’s late brother, the painter and curator Noah Davis, established with his artist wife Karon in Los Angeles in 2012. Located in Arlington Heights, a predominantly working-class black and Latino neighborhood, the museum was intended to bring art into the heart of a community that didn’t have access to museums within walking distance. When other institutions declined to loan artworks by prominent artists, the Davises created copies of those artworks themselves and put them on display.

Some of that same scrappy idealism is unmistakably present in BLKNWS—but it’s alloyed with the all-star casting, canny market positioning, and prime time-ready production values that Joseph has mastered in his Emmy-nominated directorial work. That puts it in a wholly different league, taking the concept of creating art-infused programming for audiences outside the art-world bubble and making it viable in a cable-TV context.

The POV, as Felker argued, is key. Remember, VICE started as a giveaway magazine filtered through the lens of Canadian dirtbag teens; Fox News gives voice to aggrieved, “forgotten” white America; John Oliver’s “Last Week Tonight” is “60 Minutes” by way of a hilarious British nerd. As a TV show, BLKNWS would be great programming. As a full-on cable channel, it could be the MTV of our generation, attracting viewers across all demographics, if Joseph and a network were able to get together and calibrate the levels and emphases of BLKNWS (probably less art and talking-head theory, more news, pop culture, and commentary).

That Joseph had trouble getting television-industry backing for BLKNWS—which instead received support from Stanford University’s Cantor Arts Center, where it was incubated—shouldn’t come as a surprise. The current media landscape is known to be less than receptive to ideas like this, with surveys finding that writers of color, and in particular black writers, continue to face bias. Progress here is slow, and it is vital for mainstream media outlets to work hard to give a platform to these voices. But if someone were to greenlight BLKNWS it would be a big, potentially transformative, step in the right direction.

So, who is going to make BLKNWS a reality?