People

Curator Attilia Fattori Franchini on the Making and the Meaning of ‘Sunrise/Sunset,’ Madeline Hollander’s Constellation of BMW Headlights

The commission marks the fifth anniversary of BMW Open Work by Frieze.

The commission marks the fifth anniversary of BMW Open Work by Frieze.

Artnet News in Partnership With BMW Group Culture

For the fifth consecutive year of BMW Open Work by Frieze, curator Attilia Fattori Franchini has staged the final part of artist and choreographer Madeline Hollander’s site-specific installation, Sunrise/Sunset. Nearly two years in the making—it was originally commissioned for last year’s ill-fated fair—and preceded by an interactive digital platform and a live intervention involving BMW i3 electric vehicles across London, it features nearly 100 recycled BMW LED headlights that have been technologically choreographed to reflect ever-changing conditions and energy cycles across time zones.

It is an existential work of art and engineering—one that had the Los Angeles–born Hollander in close (albeit remote) contact with BMW engineers, designers, and specialists. This is hardly surprising, considering how the Munich-based automaker has half a century of cultural engagement behind it. “We strive for eye-level and long-term collaborations, and most importantly, creating something together that has not been [done] before,” said Hedwig Solis Weinstein, head of BMW Brand Cooperations, Arts & Design.

On the ground at Frieze London, Fattori Franchini spoke with Artnet News about multidisciplinary partnerships and processes, as well as the evolution of Hollander’s piece.

Artist Madeline Hollander. Courtesy of BMW Group.

What led you to Madeline Hollander for the latest BMW Open Work by Frieze commission?

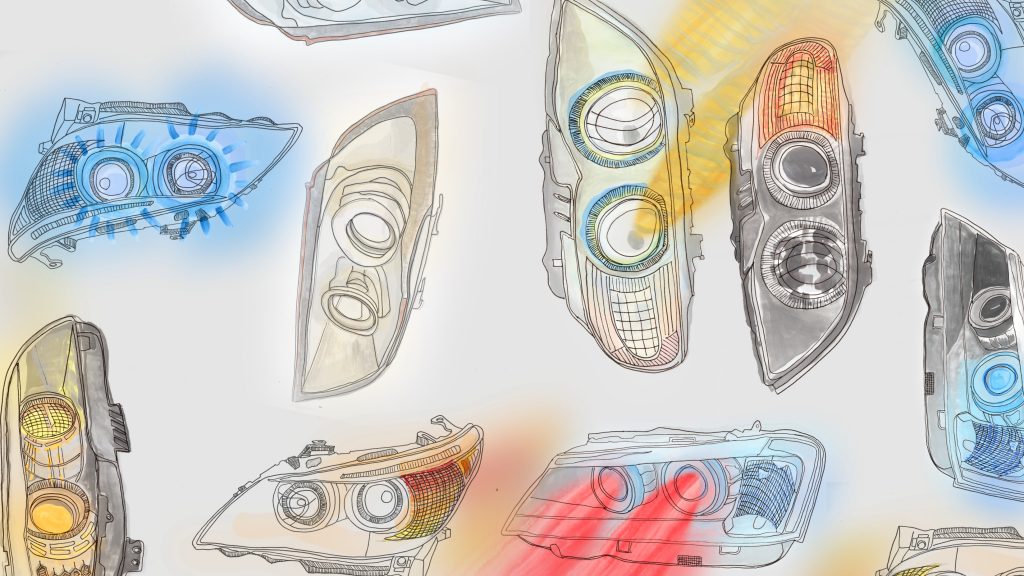

The right artist for the commission is an artist who is interested in the possibility of working with specific kinds of technologies, or [exploring] the automotive system at large. And Madeline [did] this fantastic show at Bortolami [Gallery] in January 2020, which was an installation comprised of hundreds of recycled headlights and taillights, mimicking the traffic patterns and the behavior of New York City drivers.

I was fascinated by this, first of all, because it used the raw material coming directly from cars, and second, because it could create a choreography without human actors. I felt that was perfect [for] the program, because of the possibilities for experimentation. The way Madeline looks at the world and artistic methodologies is extremely open.

Madeline Hollander, Sunrise/Sunset study (2020).

Courtesy of BMW Group.

We’d love to hear about the final part of her Sunrise/Sunset project, and the thinking behind it.

The installation is composed of 96 LED BMW headlights divided into 24 columns—each column is a different time zone. [The headlights] turn on when there’s low visibility, and vice versa, so [where] it’s lit, it’s night.

The lights are all different, from different car models, and they are massive—each about five to eight kilos. The more we look at them, [the more we] anthropomorphize [their] characteristics—they almost look like faces.

There is a score composed by Celia Hollander, the artist’s sister, inspired by the sound of [turn-signal] lights. It’s one of those white cacophonic noises that relax you, imagined to accompany the shifts in the installation.

Madeline [takes] elements from our reality and translates [them] into complex installations and performances. The project mimics sunrises and sunsets throughout our planet. It brings to the foreground cycles that we never see—or that we do see, but never acknowledge as something that defines our everyday existence.

Madeline Hollander, Sunrise/Sunset detail (2021).

Courtesy of BMW Group.

What was it like for you and Madeline to collaborate with BMW? Surely there were some interesting conversations between the artist and the engineers.

Engineers have very specific knowledge which often leads to extremely complex conversations. As much as I can understand the concept of headlights technology, the working background of it, when they start showing technical plans and drawings, my knowledge stops. But Madeleine is able to speak [on their] level, because she’s worked with so many different types of [experts] throughout her [career].

The amazing part of working with them is that they come from a specialist perspective. They have spent years and years [making] sure that components of the car could do exactly what they are asked to do. [Often], artists [make these components] dysfunctional, appropriate [them], and then use [them] for their own plans.

There were a lot of small misunderstandings that were quite funny. The other department that we worked with was the recycling and sustainability center. We were looking for [a range of] lights, even battered [ones], to create a landscape that could speak in different directions. We would be like “Give us the ones that are, like, slightly broken—we don’t mind!” For them, this request was completely crazy.

The piece was originally commissioned for Frieze London last year, and then for Frieze Los Angeles earlier this year—both canceled. How have all of the stops, starts, and shifts of the last year and a half impacted your work?

We started working together in February 2020. We made these plans to go to Munich, because part of the project is giving [the artist] access to [different BMW] departments. Obviously [with] the pandemic, there was the impossibility of traveling; everything had to happen remotely.

Madeline and I never met in person, but we were lucky because we had the chance of working together for [nearly two years], rather than [one]. This allowed the work to expand into different directions and different media—also as a digital animation and an intervention [with BMW i3 electric vehicles during Frieze Week in London last year]. And the fact that we’ve been able to realize Madeline’s core idea makes us proud.

Madeline Hollander, Sunrise/Sunset study (2020).

Courtesy of BMW Group.

What do you find most interesting about working at the intersection of art, design, engineering, and technology?

In general, part of my practice is the creation of contexts that are alternative. I recently got a three-year grant with artist Ursula Mayer to research at the University of the Arts Vienna, investigating the relationship between artificial intelligence and artistic narratives [while creating] a digital platform.

I’ve always been interested in looking at the possibilities of different fields and how they could have an impact on artistic methodology and thoughts. And the BMW Open Work commission really offers that—we invite artists to expand their practices [through] access to technology and expertise that they would not normally have.

This is the fifth year of BMW Open Work by Frieze. How has it evolved over time? And what’s in store for its future?

The program has evolved with its artists. In 2017, Olivia Erlanger talked about [ecology with] a soundscape installation and motion-sensitive benches that could activate the sound.

The next year, Sam Lewitt went into the most secretive part of BMW, which is the motors department. We could not make any documentation—any information sent to us had to be deleted. He started looking at this to reflect on copyright infringement.

Then, Camille Blatrix went into the bespoke department at BMW to think about desire. And Madeline is the first one thinking about movement, with a choreographic background.

BMW’s departments are varied and there’s so much expertise, and I like to let the artists freely engage with this expertise. So I feel part of our future is to expand the practices that we invite to work with this technology. We can definitely look into film, and more performance. I see this trajectory as infinite.

Madeline Hollander, Sunrise/Sunset (2021).

Courtesy of BMW Group.