Art & Exhibitions

MoMA Plans Its First-Ever Solo Show of a Black African Artist

We spoke to curator Sarah Suzuki about her survey of Congolese sculptor Bodys Isek Kingelez.

We spoke to curator Sarah Suzuki about her survey of Congolese sculptor Bodys Isek Kingelez.

Brian Boucher

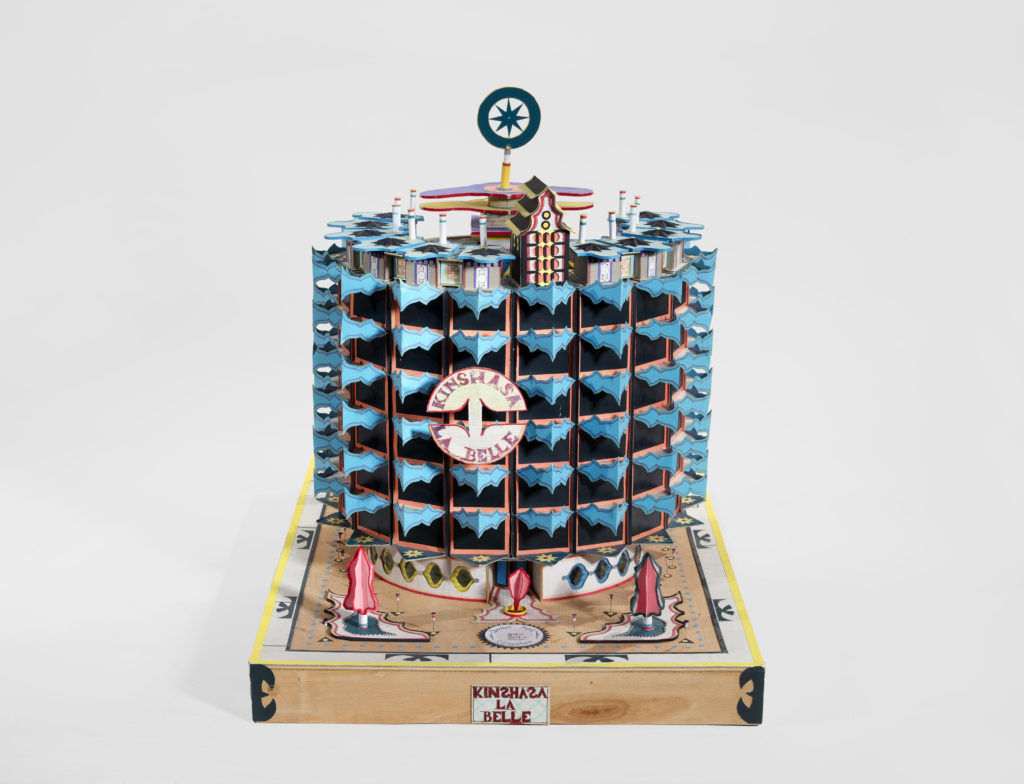

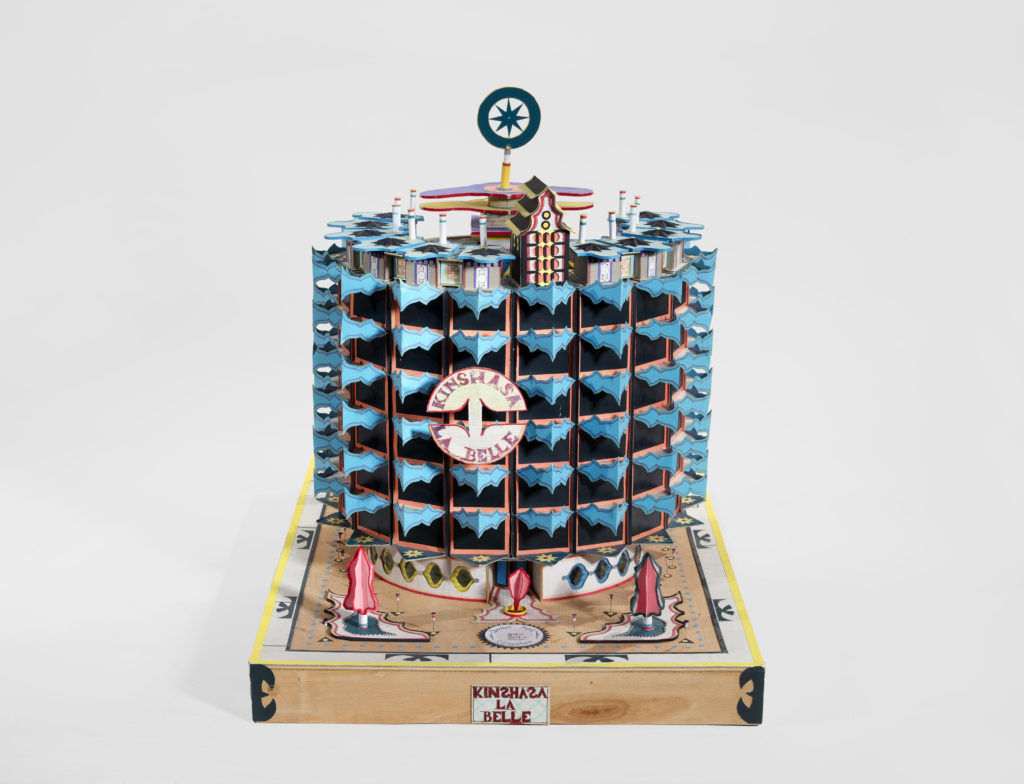

Museums in the Western world are working hard to broaden the cultural scope of their programs to make up for longstanding Western-centric blind spots. Next year, New York’s Museum of Modern Art takes another big step in the right direction with the first full-dress retrospective for the stunningly inventive Congolese sculptor Bodys Isek Kingelez (1948–2015).

Born in the village of Kimbembele-Ihunga, Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Zaire), the self-trained artist started out as a museum conservator before creating what he called “extreme maquettes.” Wildly colored and obsessively detailed, Kingelez’s tiny buildings and cities refer to wide-ranging styles, from pagodas to Dutch gables. From humble materials, the artist constructed joyous objects that possess a real grandeur.

Kingelez has been seen in numerous high-profile group exhibitions, including, just to name a few, the landmark “Magiciens de la Terre” at Paris’s Centre Pompidou in 1989, and more recently “The American Effect” at the Whitney Museum of American Art, in 2003. In 2002, he appeared in both Documenta XI in Kassel and the São Paulo biennial; and he participated in the Johannesburg Biennial in 1997.

Nevertheless, the breadth of his achievement remains under-known, and MoMA is pulling out the stops for Kingelez this time. In addition to the exhibition itself, artist Carsten Höller will organize a “visitor experience project” to accompany the show, while the catalogue will include a text by the celebrated architect David Adjaye.

Recently, curator Sarah Suzuki spoke by phone with artnet News about the historic challenges and opportunities of the exhibition.

Bodys Isek Kingelez, Kimbembele Ihunga (detail) (1991). Courtesy of CAAC-The Pigozzi Collection.

How would you characterize the artist’s vision?

It is truly a singular vision. He developed a practice that he honed to perfection and that looks like absolutely nothing else that I know in the world. He was highly technically accomplished, not naïve in any way.

There’s very limited writing on the work, maybe two paragraphs in catalogues for group shows that included him. Most writers see his as a utopic view, whereas some read the work as being about the failures of Africa in general and post-independence Congo in particular.

He saw himself as able to help people understand how to live in a more harmonious, peaceful, beautiful, lively, world, one with candy-colored, translucent structures that constitute a proposal for how to live better.

Bodys Isek Kingelez, Kinshasa la Belle (detail), 1991. Courtesy of CAAC-The Pigozzi Collection.

How do you conduct the scholarship for a show like this, where, as you say, existing writing is very scant?

It’s a different type of research and writing than I’ve done. When you’re working with a living artist, you have the opportunity for long conversations, to get a sense of how your reading fits or doesn’t fit. If you’re working on Toulouse-Lautrec, you have generations of terrific scholarship to go on. You can talk to the dealers the artist worked with, the artists he competed with.

Kingelez was in a different milieu, living his entire life in Kinshasa, so the same kind of known network of patrons, collectors, and journalists is not really there. You have to reconstruct it. It’s like a forensic detective research project. You have to find out who was the head of the Centre Culturel Français in Kinshasa in the mid-‘90s, or who was heading up the Musée national de Kinshasa where he worked as a restorer in the ‘80s.

Bodys Isek Kingelez, La Belle Hollandaise (detail), (1991). Courtesy of Groninger Museum.

What did that kind of professional background, as a restorer, mean for him?

He was working with objects that in his opinion were essentially dead. [The museum] collected ritual objects, which were meant to be used, but that, once collected, were not so meaningful. So he was asking himself, why am I doing this?

Who were some of his early advocates?

There are people like André Magnin, who was on the curatorial team for “Magiciens de la Terre” and was assigned to work on Africa and decided Kingelez should be included. Magnin then went on to work for [the art collector] Jean Pigozzi, who was gobsmacked when he saw the work and built a terrific collection, based in a long-term dialogue between him in Paris and the artist in Kinshasa.

Talking to all these people with great knowledge of the artist enables you to provide as nuanced and multifaceted a view of the artist as possible. There are also collectors and dealers and patrons in Belgium that have long-standing relationships. But it’s really forensic detective work. You’re trying to track down the email addresses of people who worked with him 40 years ago to see if they have anything to share. When they do, it’s ridiculously exciting.

Bodys Isek Kingelez,La Belle Hollandaise, (1991). Courtesy of Groninger Museum.

You say that his was a unique view, but some Western counterparts do come to mind, like Chris Burden’s Metropolis or French utopian architects.

That’s true. There’s something about the charm of the miniature. You think also of James Casebere or Thomas Demand, who are building sets out of paper. They also engage in the idea of world-building. And visionary architects of post-revolutionary Russia.

But the African context is so important. In Kinshasa, some of these seemingly fantastical buildings had a place in reality, after Mobutu Sese Seko seized power in 1965 and was interested in sending messages through architecture. [Mobutu] built two massive palaces, and invited Chinese engineers and architects who built authentic pagodas. One of the compounds is actually where George Foreman and Muhammad Ali stayed at the time of the “Rumble of the Jungle.” He also instituted something akin to a world’s fair with pavilions for countries that were interested in doing business with the Congo.

So when you look at this kind of rich combination of different factors—the Art Deco buildings erected by the Belgians, then a post-independence ambition—it’s all there in the soup. But no one does with it what he does with it.

“Bodys Isek Kingelez” will be on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, May 26–October 21, 2018. The show is organized by curator Sarah Suzuki and curatorial assistant Hillary Reder.