Art & Exhibitions

Brazil Will Turn the Spotlight on Indigenous Artists at the 2024 Venice Biennale

Focusing on the Tupinambá peoples, the exhibition “tells a story of indigenous resistance in Brazil,” according to its three curators.

At this year’s Venice Biennale, Brazil’s representatives will shine a light on their home country’s indigenous peoples, once brought to the brink of extinction by colonial rule and now fighting to reclaim what was taken from them.

The mission starts with the name of the exhibition site, which has been rebranded from the Brazilian Pavilion to the Hãhãwpuá Pavilion—a reference to the Pataxó people’s word for the territory before it was colonized by the Portuguese. Artist and activist Glicéria Tupinambá has been tapped to take it over in collaboration with Tupinambá Community of Serra do Padeiro and Olivença, Bahia, but hers isn’t the only work that will be on view. Artists Olinda Tupinambá and Ziel Karapotó also have contributions planned.

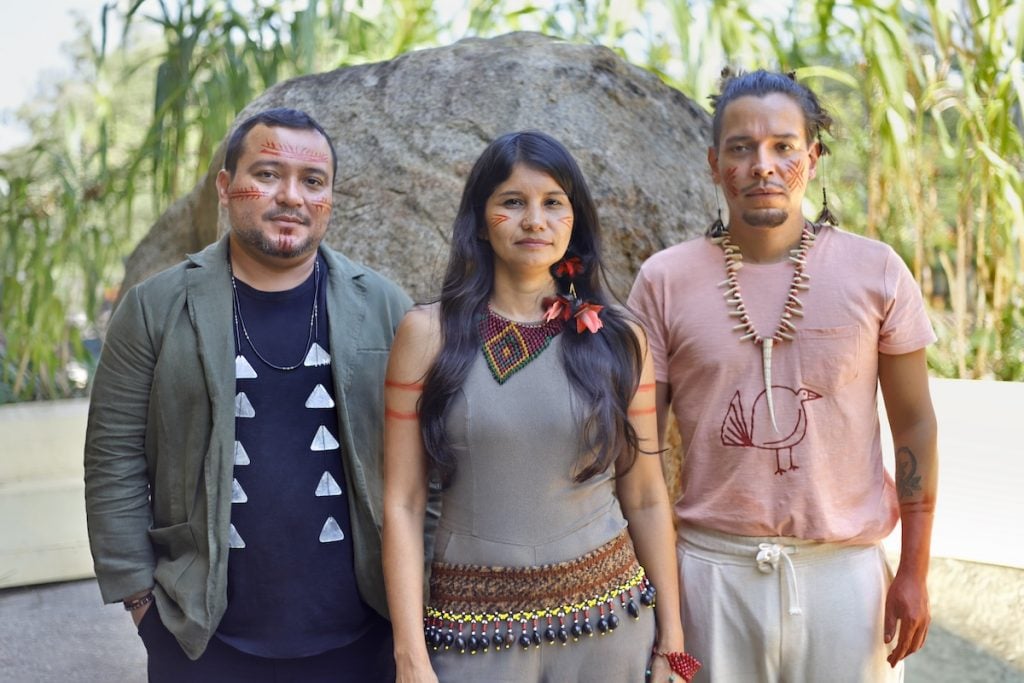

For Denilson Baniwa, Arissana Pataxó, and Gustavo Caboco Wapichana—the three curators behind the Hãhãwpuá Pavilion—a communal approach was central to the message.

“The show brings together the Tupinambá Community and artists coming from the coastal peoples—the first to be transformed into foreigners in their own Hãhãw (ancestral territory)—in order to express a different perspective on the vast territory where more than 300 indigenous peoples live (Hãhãwpuá),” the curators said in a joint written statement.

For them, the Hãhãwpuá Pavilion “tells a story of indigenous resistance in Brazil, the strength of the body present in the retaking of territory and adaptation to climatic emergencies.”

Curators Denilson Baniwa, Arissana Pataxo, and Gustavo Caboco Wapichana. Photo: Cabrel. Courtesy of the São Paulo Biennial Foundation.

“Ka’a Pûera: we are walking birds” is the name of the show planned for the pavilion—and it too says a lot about how the curators are thinking of their Venice project. The key phrase, Ka’a Pûera, is a portmanteau that suggests dual allusions: first, to a type of cropland that, after being harvested, yields a wave of low-lying vegetation; and second, to a small bird that expertly camouflages itself in dense forests.

Both images reflect the Tupinambá, who were considered extinct until 2001, when they were finally recognized by the Brazilian State. In this sense, the Tupinambá are both birds and resurgent croplands: nearly erased but never gone, powerful in their ability to blend in, more powerful when they demand not to.

Artist Glicéria Tupinambá. Courtesy of the São Paulo Biennial Foundation.

A series of mantles—capes made by the Tupinambás—are included in a pavilion installation planned by Glicéria Tupinambá, who has pushed to have the few remaining examples from the 17th-century repatriated to Brazil. One of just 11 known mantles from this period was recently returned from the National Museum of Denmark, where it had lived since 1689. The other 10 remain in European collections.

“The garment spans time and brings the issues of colonization into the present day, while the Tupinambá and other peoples continue their anti-colonial struggles in their territories—like the Ka’a Pûera, birds that walk over resurgent forests,” the Hãhãwpuá Pavilion said.

Glicéria Tupinambá, Manto tupinambá (Tupinambá Mantle) (2023). Courtesy of the artist.

“We are living in a moment of convergence between the past, the present, and the future, in order to find a path towards sustainable ways of life and a rethinking of human relations,” said Andrea Pinheiro, president of the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo. “The questions raised by the work of the curators and artists point to relevant paths for the arduous process ahead of us.”

The concerns of the Hãhãwpuá Pavilion mirror those of the main exhibition at this year’s 60th Venice Biennale, organized by another Brazilian curator, Adriano Pedrosa. A sprawling presentation of 332 artists titled “Foreigners Everywhere,” his planned show is all about outsiders. The exhibition includes numerous indigenous artists—including the Brazilian collective Movimento dos Artistas Huni Kuin—who are, according to Pedrosa’s curatorial statement, “frequently treated as [foreigners in their] own land.”