People

The New Innovators: Cuseum Founder Brendan Ciecko on How Museums Can Up Their Digital Game Without Paying an Arm and a Leg

Ciecko explains how his startup helped museums embrace modern technology, and what opportunities lie ahead.

Ciecko explains how his startup helped museums embrace modern technology, and what opportunities lie ahead.

Tim Schneider

The New Innovators is a four-part series of long-form interviews with change-making art-world figures originally featured in Artnet’s Fall 2020 Intelligence Report.

In 2014, Brendan Ciecko founded Cuseum, a startup committed to helping cultural organizations slough off their late-adopter stigma and embrace modern technology to bring the visitor experience into the 21st century. Today, Cuseum is a leader in the field, with hundreds of institutional clients of varying sizes around the globe, ranging from SFMOMA and the Nasher Sculpture Center, to the National Museum of Wildlife Art and the Davis Museum at Wellesley College.

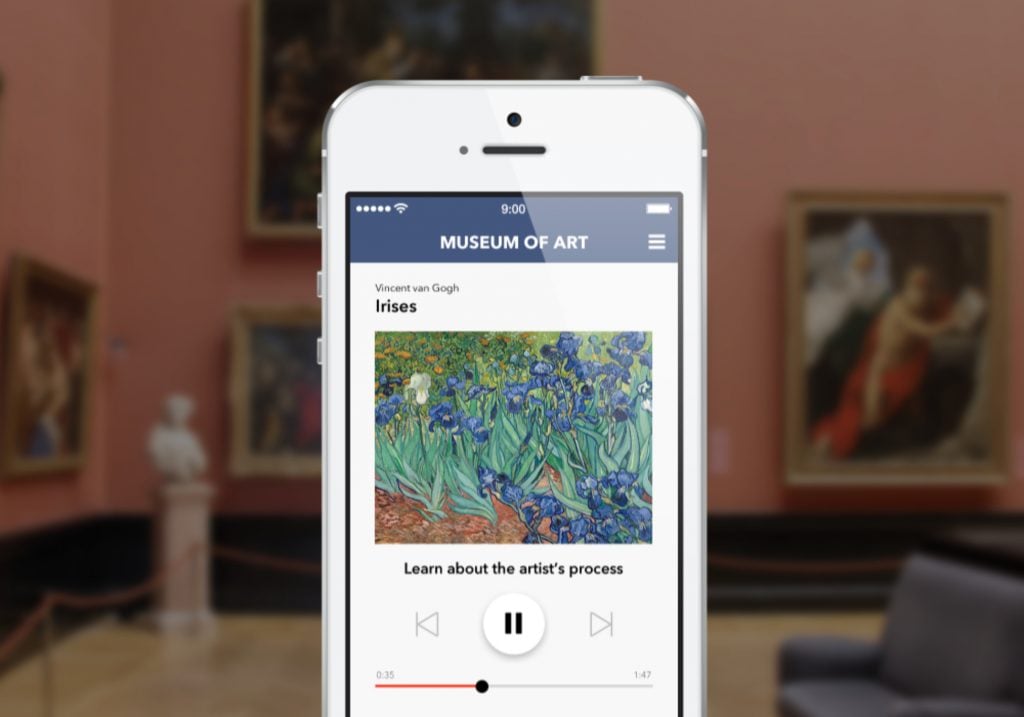

At the foundation of Cuseum’s future-facing offerings are two core products: an award-winning “digital docent” that provides a self-guided, multilingual, multimedia-enhanced alternative to standalone audio guides; and digital membership credentials that offer a green replacement for old-fashioned printed cards. Both products run on visitors’ smartphones, making their trips to the museum richer and easier, while also handing institutions turn-key technological solutions that save time, reduce waste, and slash expenses.

Artnet News recently selected Ciecko as one of its New Innovators, 51 professionals pushing the art industry forward from a variety of different sectors and areas of expertise. The New Innovators list leads the Fall 2020 Artnet Intelligence Report.

The conversation with Ciecko below, conducted by Artnet News’s Tim Schneider, is an expansion of Ciecko’s entry on the list, affording him more space to discuss his unique path to the present moment, his perspective on the evolution of the arts and culture sectors, and the opportunities to be found in the challenges that lie ahead. Answers have been condensed and edited for clarity.

I’m curious: when you pitch Cuseum to somebody who doesn’t know anything about the company, what do you say?

First and foremost, our company is dedicated to helping museums and cultural organizations succeed in the digital era. When we started the company, our goal was set on how we create the most engaging and satisfying educational experience for every visitor who makes their way to the museum or other cultural venue.

We’ve since expanded into [asking]: how do we help these organizations, these museums, succeed holistically? How do we find ways to build efficiencies and cost savings so that the byproduct is a better experience for the visitor and a more engaging relationship with the member? Those are really the core functions of what we do here.

What originally interested me in Cuseum is that you started approaching these questions from the perspective of an art outsider. Can you tell me a little bit about your background before you launched the company?

The Pioneer Valley, the region of Massachusetts where I grew up, is very working class, very industrial. I’m the son of a plumber and a school bus driver. I did not really grow up going to art museums or art fairs or things of that nature. It wasn’t until my late teenage years and early twenties that my interest and my appreciation [in art] really started to evolve.

I had built the first chapter of my life in the music and entertainment industry. I’m self-taught and self-driven. I’ve been designing and developing technology since I was around 11 or 12 years old. I founded a creative agency when I was 13, so during junior high school and high school, I was designing and building websites, marketing materials, mini-applications, and stuff like that for record labels. I’d worked with Katy Perry, Lenny Kravitz, Mick Jagger, and all of these [other] great entertainers. And as this [became] a lucrative company, I had the means and independence in my life to travel, to see the world, and to get exposure that I didn’t have previously.

When I moved to Boston, I got involved with the Museum of Fine Arts, and my eyes were opened to this access that I never had. And then around 2010, one of my favorite museums in New York reached out to the company that I founded about completely revamping their online presence—they didn’t have a chief technology officer or chief digital officer during that time—and we took on the opportunity solely out of my passion for this museum.

Cuseum brand image. Courtesy of Cuseum.

What made you feel like the museum experience was such an urgent problem to solve that you couldn’t resist making this sharp pivot into a very different line of work? Or were you just looking for a new challenge?

Across all of the museums that I had interacted with as a patron, I just saw how broken and flawed and frustrating and obsolete a lot of the tools they had at their disposal were—and how they were going to be left behind in this digital transition that was taking place.

By 2013, we were really seeing and experiencing everything on our mobile devices, yet here were these clunky old [museum] audio guides. I started really thinking about museum experiences and how those could be transformed in ways that were more accessible, more engaging, and [wouldn’t] cost the museum an arm and a leg to have some level of modern standard for their visitors.

I’m assuming Cuseum officially came into being sometime during that first museum project.

Paul English, the founder of Kayak.com, said that he wanted to invest in my company. And the only way [someone can] invest in a company is to actually have a company to invest in! So I pinged my lawyers and drew up the paperwork. I think it was August 1, 2014, when I incorporated [Cuseum] and said, “I’m swinging full time on this.” But there were many more years and experiences that led up to that leap.

So then how did you start to build out an understanding of what might qualify as viable solutions for art museums’ technological shortcomings?

To familiarize myself with the space during that first opportunity, I started kind of blindly reaching out to notable leaders in the museum field—people like Rob Stein, who was transforming the Dallas Museum of Art with director Maxwell Anderson, and Jane Alexander, who is still the [chief digital information officer] at the Cleveland Museum of Art. She was getting a lot of positive attention for the waves that the CMA was [making] in the cultural sphere.

It seems like late 2013 and early 2014 was when there was a surge of interest and inspiration around how museums were taking to the internet or leveraging emerging technology in ways that they hadn’t done previously. Don’t get me wrong, museums have had websites since the ‘90s, but we’re talking about really making it a more significant part of their operation.

For sure, there’s a vast difference between having a website that technically functions and having a forward-thinking, useful set of digital tools.

Yeah, I think museum professionals are already way overworked. They have so many responsibilities on their shoulders, and digital literacy is now starting to be prioritized in a new way. So just by bouncing around the global community, we [at Cuseum] often get our hands on pretty interesting research and development endeavors that are slightly outside the scope of [the culture sector] in the pursuit of understanding, the pursuit of knowledge, and wanting to advance this field. But it always goes back to the museum community.

Right, you’re learning what else is out there and figuring out how it might relate back to museums so they don’t have to. That seems like it would be especially valuable this year, which, to massively understate the case, has not unfolded the way we thought it would when the clock struck midnight on January 1, 2020. How has the shutdown influenced Cuseum’s focus?

In terms of our strategy as a company and the strategy for surviving and thriving as a cultural sector at large, I think an unexpected thrust has been looking at the dynamics related to the remote experience or the modified physical-digital experience. It’s probably going to be a multi-wave [scenario] where museums are open, then closed, then open, then closed [again]. So it’s going to be a really confusing and bumpy road for the public.

We want to equip museums with everything they need to engage you on site and keep you safe, [like] encouraging social distancing and a contact-free experience. And then when the museum is closed or when there’s a reduced capacity, how do I access at least some highlighted components of that museum’s collection remotely? Maybe that is augmented reality—we’ve done a lot of work in that area—or maybe it’s other things. We’re doing a lot of research and experimentation and prototyping around all of those dynamics, [asking] “What does an organization need to be successful during this unprecedented moment in time?” So that’s the core focus, the core strategy driving product [development] right now.

One of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum paintings stolen in 1990, Rembrandt van Rijn’s Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee, returned to its frame through the magic of augmented reality. Photo courtesy of Cuseum.

Let’s take an even longer view. What do you think the art world, or specifically the museum world, will look like five years from now? How will the field be different in 2025?

I think all of the things that have been historically placed on the back burner—especially as they relate to the digital arena, the virtual arena, the remote arena, and how people engage with experience, consume, and even purchase art and culture—that has been thrust into our laps in a way that we never could have imagined. To me, that is the unexpected accelerator of innovation and progress in the sector. Those are two different mindsets: “progress” as being all-flourishing, “innovation” [as being] about all of these new tools, methodologies, and technologies.

But I think, overall, people up and down the ladder now understand the importance around digital, around emerging technology, around immersive experiences. And so a lot of the conversations that I’m getting pulled into right now are [about] solving infrastructure problems that have been in existence for decades. Firming up that platform is going to create a much more sustainable arts and cultural sector for the next era.

Other than that mindset and necessity, it’ll be a far more digital—and far more accepting of digital—environment. Just looking back five or 10 years ago, there were a lot of preconceived notions about the [limited] role technology plays in mediating art and culture on the commerce side. And now we’re living in a world where the major auction houses are talking about artificial intelligence; you have a lot of museums launching new immersive platforms; you have cultural leaders experimenting with [blockchain]. That appetite and that attitude is fairly new, and it’s just been accelerated more than anyone could have ever imagined. That’s how I’m looking at things right now.

Overall, then, it sounds like you’re encouraged by the trajectory of the art world over the past few years. But if there was one aspect of it that you still wish you could change about the industry, what would it be?

I think formalism and traditionalism have frozen its progress in time a little bit. Any way you slice and dice it, the masses look at the art world as being fairly elitist and somewhat intimidating. But I think all of that is shifting, and it will continue to shift as things stabilize in the new world that we’re entering.