In a longstanding art feud, two Brooklyn families are locked in a bitter dispute over the ownership of a painting by Claude Monet that, if authentic, is claimed to be worth $100 million.

In September 2014, the heirs of David Arakie sued Shaya Gordon and his siblings in Kings County Supreme Court for the return of Women at Arles and six other works of art.

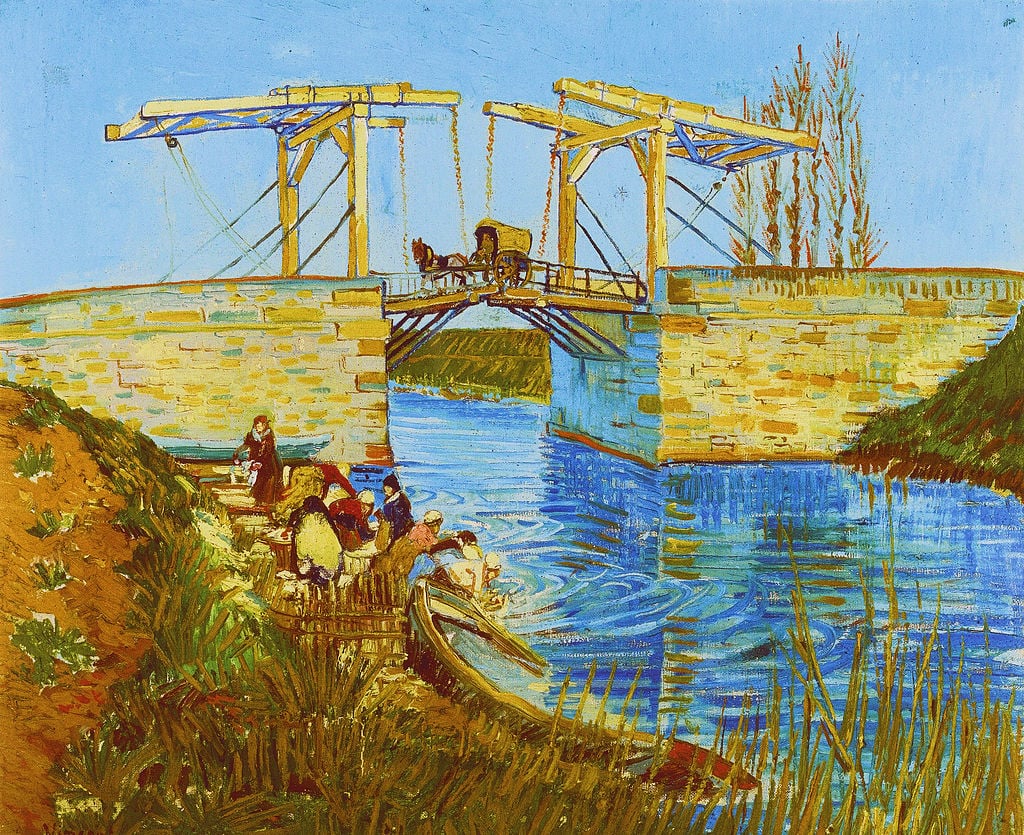

Though Gordon now claims that the Monet painting is just a well-made fake, the canvas appears to bear the artist’s signature. Southampton’s Parrish Art Museum reportedly showed Women at Arles as the genuine article back in 1973.

The story of Women at Arles goes back decades. In 1971, Arakie, an art collector, gave his son, Steven Dearakie, the canvas with the understanding that Dearakie and his siblings would each get a one-fifth share in the artwork upon his death.

Arakie died the following year, but it wasn’t until 2003, when Dearakie found himself in dire financial straits, that the painting’s ownership came into question.

After costly divorce proceedings, and a precipitous decline in health from advanced Parkinson’s and a series of strokes, Dearakie was introduced to Gordon’s father, Schabse Gordon, known in the Jewish community for providing financial assistance and described in the complaint as a “known Jewish philanthropist with extensive expertise in art.”

Dearakie’s family maintains that in addition to arranging a $100,000 personal loan for Dearakie’s mortgage, Schabse agreed to help the family sell seven artworks, including Women at Arles. The paintings were delivered to Schabse in December 2003.

Shaya Gordon tells the story differently, claiming in an affidavit that the artworks were a gift. “My father was a very generous man and helped out many people financially,” he wrote. “This included Steve Dearakie, who needed both physical and financial help. My father had informed me that in repayment of my father’s generosity, Mr. Dearakie gave my father the seven [works of art].”

A receipt entered into evidence that is allegedly signed by Schabse Gordon, acknowledging receipt of the Monet and other artworks “for appraisal.”

Photo: via WebCivil Supreme.

With informal financial arrangements, which are common within the tight-knit Jewish community, such disputes can be difficult to resolve.

Regardless of why the works were in the Gordon’s possession, the family allegedly had difficulty finding a buyer for the Monet after two appraisers offered their opinion that the canvas wasn’t real.

“They both confirmed it was a very beautiful painting, but it was not a Monet,” Martin Cohen, who introduced Dearakie to Schabse, told DNAinfo. “[Monet’s] name was on the painting but it wasn’t by him.”

Monet expert Paul Tucker believes that the work is unlikely to be authentic, pointing out to DNAinfo that there is no evidence that Monet ever visited Arles (a French city often painted by Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin), and that a “brand-new, unknown and undocumented Monet is extremely rare.”

For Dearakie’s family, however, getting the painting back is top priority no matter what. “The painting does not belong to you . . . and it is totally irrelevant on whether or not in your opinion the painting is not authentic” wrote Mechel Handler, Dearakie’s nephew, in a letter to Gordon, claiming his family has “good reason to believe that the painting was worth much more than you would like us to believe.”

An insurance document for $400,000 for the alleged Monet.

Photo: via WebCivil Supreme.

While a letter from the plaintiffs’ lawyer to the judge claims the painting is worth $100 million, that number seems a bit high, even if it is an authentic Monet. The record for a Monet painting at auction, according to the artnet Price Database, is £41 million (roughly $80.4 million), for a sale at Christie’s London in June 2008.

This past spring, Monet caused a stir at auction when Sotheby’s offered six works by the artist including a painting from his beloved waterlilies series. But that painting, Nymphéas (1905), sold for $54 million.

The current conflict began soon after the Gordons received the artworks, when Schabse and Dearakie both died within two months of each other in the fall of 2004.

Dearakie’s family has been fighting to recover their property ever since, with lawsuits filed on separate occasions in Sullivan Country Supreme Court, Manhattan Surrogate’s Court, and most recently in Brooklyn Supreme Court, where the plaintiffs are seeking the return of the painting plus $300 million in damages.

The families have also attempted to work things out in rabbinical court, but the two sides have been unable to reach an agreement.

Inheritance battles are all too common when it comes to valuable artwork—see the case of Lucian Freud‘s 14 children and multi-million estate, or lawsuit over the fate of the Gurlitt trove.