Reviews

The 2024 Busan Biennale Is Eccentric, Vexing, and Full of Thrills

Is it a Documenta 15 redux? A joyful celebration of creativity? A gimlet-eyed portrait of life right now? All of the above!

Is it a Documenta 15 redux? A joyful celebration of creativity? A gimlet-eyed portrait of life right now? All of the above!

Andrew Russeth

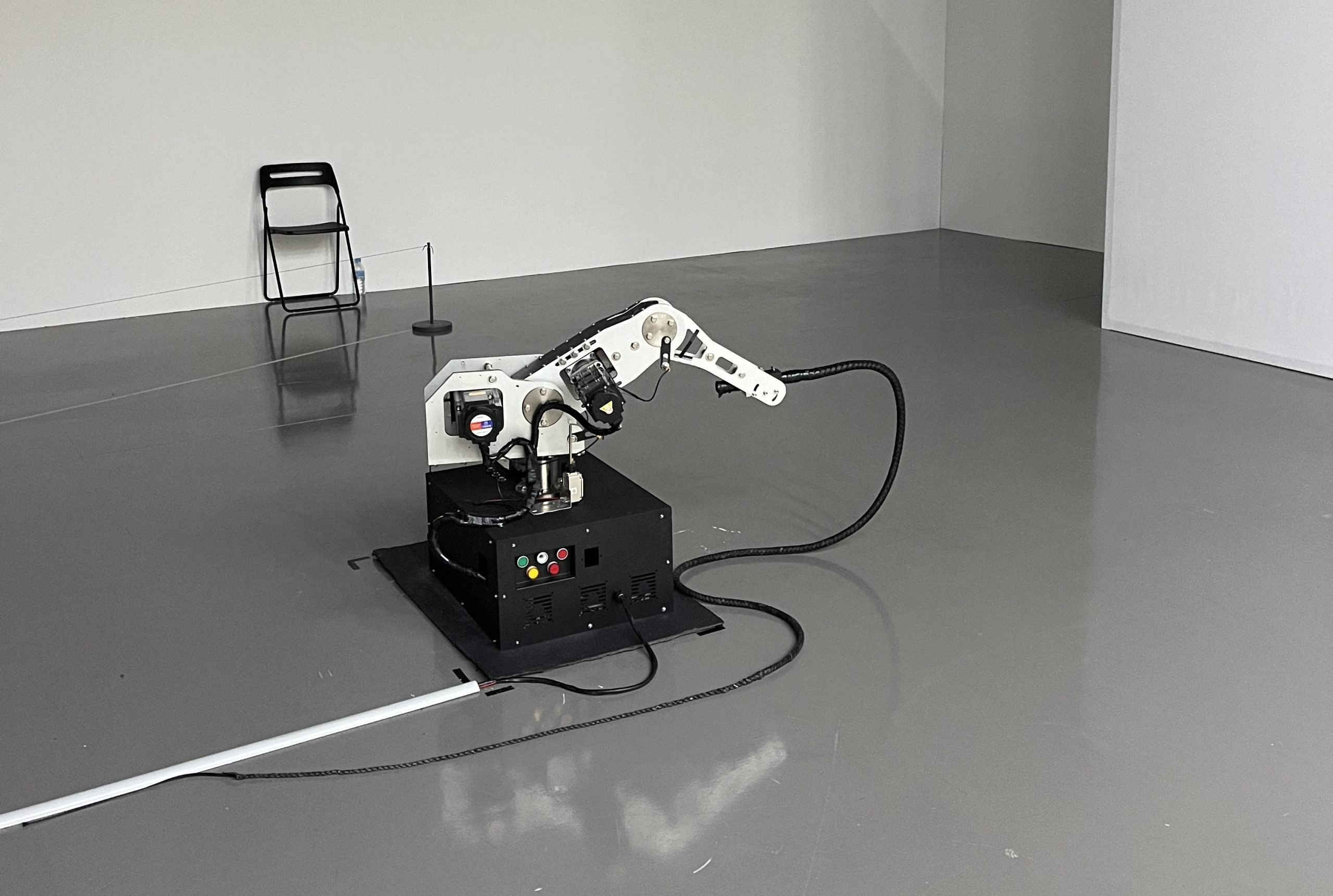

A robotic arm moves a long, black whip across the floor, and then suddenly lets it rip. Nearby, a motor pulls a knife on a wire toward the ceiling. Without warning, the blade falls, puncturing a wooden table. Low stanchions separate you from these works, which are by, respectively, the Vietnamese artists Nguyễn Phương Linh and Trương Quế Chi, but they are still quite menacing.

Partial installation view of Nguyễn Phương Linh & Trương Quế Chi’s Sourceless Waters: The Whip & The Knife (2024).

Another room here at the Busan Museum of Contemporary Art in South Korea has a peculiar amount of empty white wall space. As you stare, your eyes tingle. Is it really empty? There are “three almost invisible hues of color,” a wall label explains. This is Carla Arocha’s Snow (2003/2024), which simulates snow blindness, a condition that “causes us to see dead cells as the blind spots in our eyesight.” We are “looking at our own death,” the label adds.

On a grass field outside, there is an old trailer painted with larger-than-life flowers by Doowon Lee. The self-taught Korean artist has stuffed similarly exuberant canvases inside the vehicle, along with a bevy of potted plants, creating a verdant little refuge on MOCA Busan’s island home. Across the Nakdong River, apartment buildings stretch off into the distance.

Doowon Lee’s The flower garden of BUDDHA-BEE in a caravan (2024).

Welcome to the 2024 Busan Biennale, which is by turns harrowing and sedate, almost comically blunt and frustratingly hermetic. It is one of the more freewheeling exhibitions I have seen in recent years, and also one of the more enervating. On view through Sunday, it’s titled “Seeing in the Dark”—which is difficult to do, literally speaking, but it is precisely what great artists can accomplish by developing fresh ways of looking at the world and allowing us to make sense of, yes, very dark times.

The biennial’s artistic directors—Vera Mey, an independent curator from New Zealand, and Philippe Pirotte, a former rector of the Städelschule in Frankfurt—have marshaled an admirably eclectic list of 62 individuals and groups for that task. There are big-league Korean names and a few regulars on the global art circuit, but most are not well known. This show is a bet on new talent.

Kyung Hwa Kim’s Harmony (2024), made from cloth used to make hanbok, traditional Korean clothing.

Violence is everywhere, even in unabashedly beautiful material. one hanging tapestry—hundreds of fabric flowers stitched together by the Korean artist Kyung Hwa Kim—is titled People massacred in the valley (2024). The plants are native to the site of a mass killing of leftists and alleged leftists in 1950s Korea. Kim’s work stuns, but other pieces feel overly fixated on history: Footnote Art that mines historical minutiae to no real end in wan installations and paintings, interesting enough but random.

Activism is also everywhere, for better and for worse. Subversive Film, a Palestinian collective that took part in the fraught Documenta 15 in Kassel in 2022, is on hand with a compilation of film clips from anti-colonial and worker movements. Here, too, is the Indonesian group Taring Padi, which displayed a piece with anti-Semitic imagery in that show, igniting a firestorm. Its contributions in Busan include frenetic banners from peasant protests back home and a low wall (a barricade?) made of bags of rice. (Midway through my visit, I hear a man with a Germanic accent muttering to his companion, “Documenta redux, Documenta redux.”)

“Glitch Barricade,” a solo show of protest photographer Seo Young-geol’s work that was staged as part of the biennale by Hong Jin-hwon.

There are more nuanced and fruitful approaches. One the biennial’s highlights is a miniature solo show-within-the-show of Seo Young-geol’s photographs of tense pro-democracy demonstrations in South Korea in the 1980s and ‘90s. It was organized by the filmmaker Hong Jin-hown, who’s printed Seo’s images in a variety of sizes, pasting some to the wall and framing others, building a chaotic collage of people chanting, waving banners, crying. In a neighboring theater, Hong has a two-channel documentary, Double Slit (2024), that looks at how leaders of those protests became elected officials, abandoned radical aims, and formed a new establishment. Post-viewing, those heroic snapshots are tinged with melancholy.

Yun Suknam, a pioneering feminist artist in Korea in her mid-80s, has a series of affecting portraits of women involved in the nation’s fight for independence from Japan in the early 20th century. No depictions remain of some of these figures, who worked in obscurity, so Yun drew on archival texts, using pencil and pigment to make the only ones that now exist. And in a chilling video by the Chinese artist Chen Xiaoyun, Night/2.4KM, the camera follows a group of young men—construction workers or farmers, perhaps—as they march through the night. They are carrying sticks and shovels, as if headed toward a brawl, but they never arrive. They just keep going. The piece is from 2009, but it feels awfully of the moment.

A partial installation view Mugunghwa Pirates (2024), portraits of South Korean presidents as pirates by of Koo Hunjoo, who also works under the name Kay2. It’s on view at the Busan Modern and Contemporary History Museum.

The biennial’s stated themes are doozies: “pirate enlightenment,” borrowing from anthropologist David Graeber’s eponymous 2023 book, which posits that communities formed by descendants of pirates in 18th-century Madagascar helped inspire the European Enlightenment, as well as Buddhist enlightenment. (These phenomena provide means of “seeing in the dark,” in a very expansive sense, you might argue.) Pirate and Buddhist iconography get big play here.

Seven pirates smile from gold frames in the basement of the Busan Modern and Contemporary History Museum, one of the biennial’s three satellite locations. They’re the work of a Busan street artist named aka Koo Hunjoo, a.k.a. Kay2, who has literalized Graeber’s thesis by taking spray paint to official-looking portraits of South Korea’s democratically elected presidents, détourning the besuited politicians with black hats, scrappy beards, and missing teeth. It’s goofy, but it does have a certain piquancy following the uproar caused by a high school student’s amusing caricature of the current president (as Thomas the Tank Engine, controlled by his wife).

Eugene Jung’s W💀W (Waves of Wreckage), 2024.

Back at the museum, the young gun Eugene Jung, who works in Seoul and New York, ripped open walls to a gallery where she scattered about all sorts of construction materials (plywood, steel pipes). The 2024 work, W💀W (Waves of Wreckage), “resembles a temporarily wrecked pirate ship,” a wall label claims, and while I can’t quite see that, I am impressed by the raw energy, the mayhem, of the effort—a reasonable response to life right now. On the roof of an abandoned house in the heart of this city of 3.5 million, Jung placed rugged, charred sculptures that could be fragments of an enormous sphere that has been cracked open in some unnamed disaster. (It vaguely recalls Fritz Koenig’s 1968–71 Sphere, which was smashed on 9/11.)

In some of the most potent work in the biennial, artists invent new languages or create private worlds. There’s the Jamaican American Douglas R. Ewart, who makes charismatic instruments out of things like crutches and cake pans, paying tribute to people like Sun Ra and George Floyd; Doowon Lee, with his joyful garden paintings; and the Togolese-Belgian photographer Hélène Amouzou, who toys with camera techniques to make unforgettable black-and-white self-portraits where she has a furtive presence, there and not there, only giving her viewers so much.

Daejin Choi, And, nothing was said, 2024.

The work that has really stuck with me, though, is one of the most traditional. It’s a massive ink drawing on paper, à la Raymond Pettibon, by the Korean artist Daejin Choi, and it shows about a dozen elite South Korean commandos in a raft (the kind of subject that rarely appears in exhibitions of vanguard-minded contemporary art). These soldiers are wearing wetsuits and goggles, training, perhaps prepping for some clandestine strike. You might think of it as a companion piece to Arocha’s nearly invisible Snow.

Death hovers in the air here, too, but with cold clarity. Choi has rendered these men with loose brushstrokes, and it almost looks like they could evanesce into a pool of ink at any moment. For now, though, we can see them clearly.

See more images of the Busan Biennale below.

Carla Arocha’s Snow (2003/2024), a wall painted with almost invisible color.

Partial installation view of Shooshie Sulaiman and I Wayan Darmadi’s PETA – One cloud, nine drops of rain (2024) at Choryang House.

Installation view of Nika Dubrovsky’s three-channel video work Fight Club (2022) at the Hansung1918 venue.

Cheikh Ndiaye’s Le Paris (2024) at the Busan Modern and Contemporary History Museum.

Absolutely wild photographs by Oladélé Ajiboyé Bamgboyé at the Busan Modern and Contemporary History Museum.

At left, Joe Namy’s Dub Plants (2024); at right, Omar Chowdhury’s short film BAN♡ITS (2024).

A (nearly) empty room containing a sound work by Daejin Choi, Kim ChooJa Medley No. 2 (2024).

Daejin Choi’s Kim ChooJa Medley No. 2 (2024) slows down an album by that popular singer of the 1970s and ’80s so that it lasts 24 hours.

Single-print etchings on paper by Fred Bervoets from 1997. Each is titled Mijn Stad (“My City”).

Partial view of Ishikawa Mao’s The Great Ryukyu Photo Scroll part 10 (2023), which takes up moments in Okinawan history.

Paintings by Doowon Lee.

Tracy Naa Koshie Thompson’s Kimchi-Waakye (2024).

Ghostly self-portraits by Hélène Amouzou, highlights of the Busan Biennale.

Two paintings by Bang Jeong A, Those Enlightened in the Water, which shows a Buddhist Arhat (a saint), and Growing Claws-Becoming, both from 2024.

Golrokh Nafisi with Ahmadali Kadivar, Continuous cities, 2024.

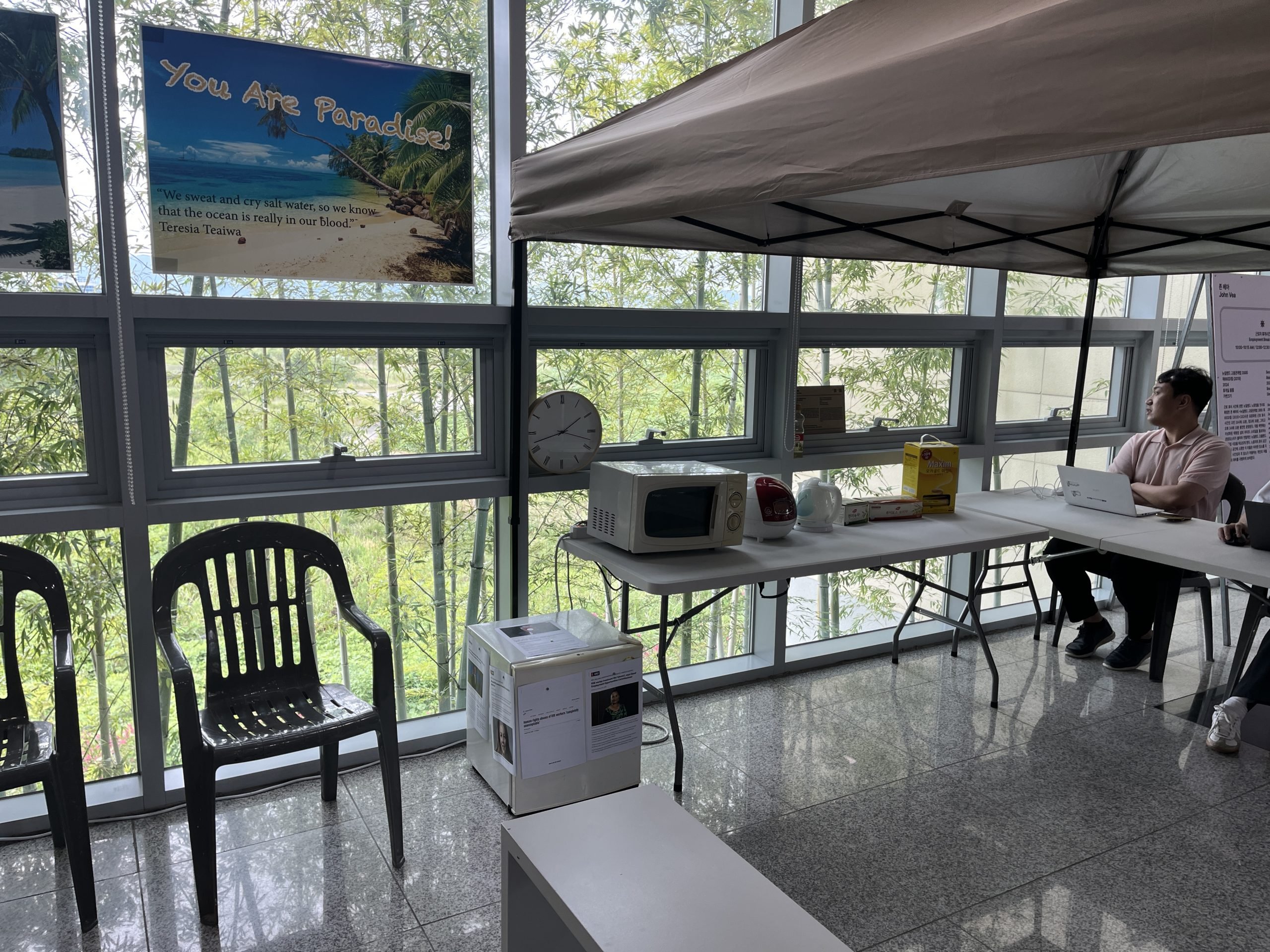

John Vea’s Section 69ZD Employment Relations Act 2000 (2019) (2024), a break room-as-installation that can be used by visitors during set break times: 15 minutes at 10 a.m., 30 minutes at noon, and 15 minutes at 3 p.m.

Installation view of the 2024 Busan Biennale, with Nathalie Muchamad’s ENRIQUE (2024) at left.

Jasmine Togo-Brisby’s short video piece It Is Not a Place (2024).

Song Cheon, Avalokiteshvara and Mary-The Truth Has Never Left My Side, 2024.

Works from Yun Suknam’s “Women of Resistance Series” (2020–23), which depict women who fought for Korea’s independence from Japan.

Untitled works by Kanitha Tith from between 2000 and 2024 at the Busan Museum of Contemporary Art.

Taring Padi’s Memedi Sawah/Scarecrow Installation (2024).

Inside Doowon Lee’s The flower garden of BUDDHA-BEE in a caravan (2024).