Artists

Loie Hollowell’s New Move From Abstraction to Realism Is Not a One-Way Journey

This month, the star painter opens two shows on opposite coasts—one a survey of the past, the other a preview of the future.

This month, the star painter opens two shows on opposite coasts—one a survey of the past, the other a preview of the future.

Taylor Dafoe

In the spring of 2020, Loie Hollowell gave birth, at home, in water, to her second child. The experience put the 40-year-old, California-raised painter in touch with her body like never before and left her reconsidering the veil of abstraction that had, to that point, blurred the female forms in her work.

Maybe “reconsidering” is too passive a word. “I wanted to make my paintings pregnant. I wanted to impregnate this masculine rectangle with full engorged breasts and pregnant bellies as a mothering act,” Hollowell recalled while munching—a little ironically—on a handful of nuts. She was sitting shoeless on a corner couch in her Queens, New York studio. The space is deceptively large and labyrinthian, but cozy—warmed in all sorts of little ways by hints of home life that have snuck in. An after-school project by one of Hollowell’s two kids is splayed out nearby; so is Felix, a rescue cat who purrs and preens as if under the impression that this journalist was there to interview him.

To some extent, Hollowell has made good on her intentions: the sacred geometric shapes she once used to evoke the body have, in the years since her delivery, been increasingly replaced with casts of actual body parts. A decisive step back toward figuration, the move has made her creations more personal—and more political. Not everyone has appreciated the pivot. “The new works I’m making with the cast body parts, people are much more hesitant to buy them,” she said. There’s some apprehension in the artist’s words on this topic, and then again when she mentions her painter dad, David Hollowell, who was once abruptly dropped by a New York gallery at the first sign of slowed sales.

This month, Hollowell opens two shows on opposite coasts: “Space Between, A Survey of Ten Years” at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut; and “In Transition,” a presentation of new bas-relief paintings at Jessica Silverman in San Francisco. One a look back at the past, the other a peak into the future, the shows symbolize a question that—for the first time since her sensuous paintings made her an overnight market darling nearly a decade ago—is hanging over Hollowell’s career: do I keep making work that I know people will like and buy, or do I push my art at the risk of alienating audiences?

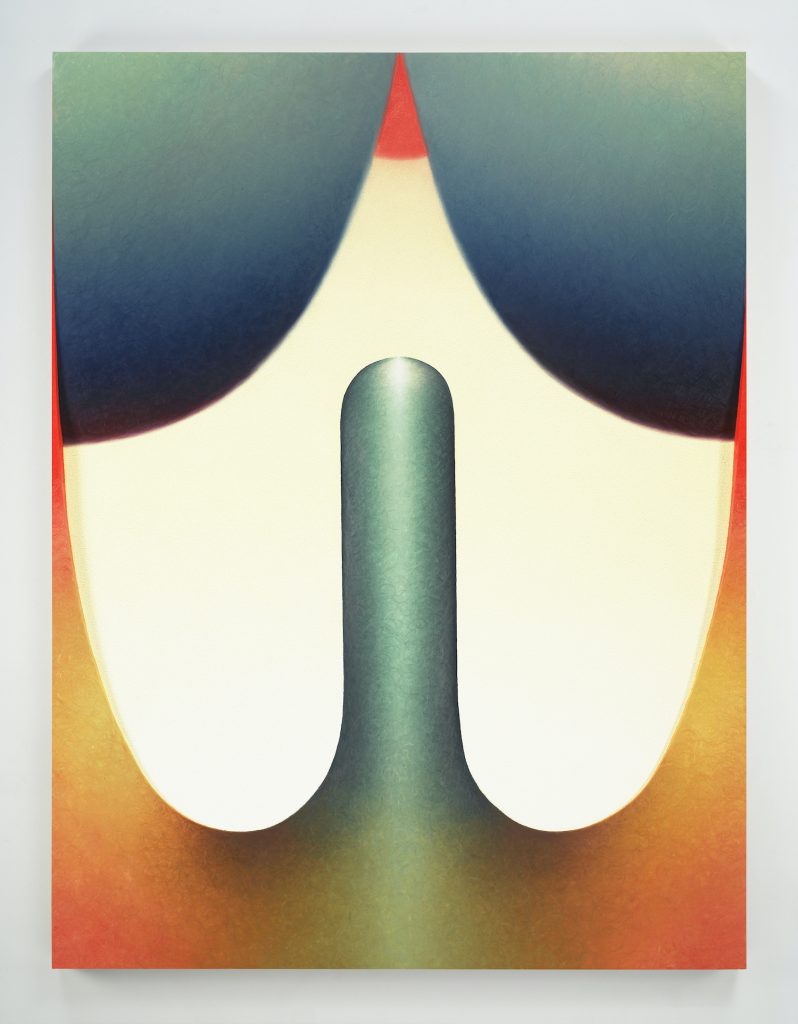

Loie Hollowell, Eight Centimeters Dilated (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Jessica Silverman.

In 2013, Hollowell was fresh from grad school—she got her MFA from Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) the year prior—and living off food stamps while making what she referred to as “cartoony figurative drawings and paintings” in her New York apartment. Then came some wholly unexpected news: she was pregnant.

The artist opted for an abortion. The experience “totally changed the direction of my work,” she explained, noting that soon after the procedure she began making graphite studies of her vagina and cervix. Two of these drawings—Emerald Mountain (2013) and Happy Vagina (2013)—will be on view in the Aldrich exhibition, and in both Hollowell can still see reflections of her mental state at the time they were made. The drawings have the emotional voltage you’d expect from work created in the wake of a major life event, but also something else, something exciting: the newfound energy of what she called “liberated feminist freedom.”

“The abortion, it was so visceral and empowering that I just started thinking about all of the experiences I’d gone through in my body,” she said. “I was like, well, there’s just a whole world of content there. I don’t have to look at anything else; everything can come from within.”

Loie Hollowell, Emerald Mountain (2013). Photo: Melissa Goodwin. Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery.

Shortly thereafter, Hollowell ran into the painter Ridley Howard, whom she had met at VCU, and began showing with his apartment-based exhibition project, 106 Green. In June of 2015, Howard brought a few of her pieces to Brooklyn’s short-lived NEWD Art Show, where they caught the attention of at least one notable collector: artist Rashid Johnson. He purchased one, a small, “challenging and thoughtful” painting centered around a floating diamond. In it, Johnson clocked the influences of “Western painting traditions,” but also whiffs of New York. “That duality was something that was unexpected to me. I just fell for it,” he said.

Johnson still owns that artwork and two more by Hollowell, which he picked up during a later visit to her studio. The purchases couldn’t have cost “more than two or three thousand” each, he explained, but his more valuable gift to Hollowell came in the months after their interactions, as he continually sang the praises of her work to two high-powered friends.

Loie Hollowell, Point of Entry (blue green mounds over yellow sky) (2017). Photo: Tom Barratt. Courtesy of Pace Gallery.

The first was dealer Joel Mesler, who bought a pair of Hollowells for $2,400 a pop during the run of her November 2015 solo show at 106 Green. He wasn’t the only fan; a New York Times review of the exhibition was laudatory and, it turns out, quite prescient. “The next time you see Loie Hollowell’s paintings it will probably not be in a small, artist-run gallery in someone’s apartment that is open only on Sundays or by appointment,” read its opening line.

Mesler offered to represent Hollowell through his newly opened gallery Feuer/Mesler. He brought several pieces of hers to NADA Miami in late 2015, then mounted a solo show of her work—crucially, the artist’s first to feature three-dimensional sculptural elements atop her paintings—the following year. In both cases, Hollowell’s work sold out immediately. “It was crazy,” said Lauren Marinaro, a Feuer/Mesler partner who has since opened her own eponymous gallery. Interest in Hollowell’s art “went almost from zero to basically…” the dealer paused, then exhaled—her sentence suspended but her point communicated. “And it wasn’t just that people wanted it; it was like the highest end of people wanting it.” Interested parties, Marinaro added, included two ultra-blue-chip dealers and a pair of husband-and-wife collectors who ran a private museum.

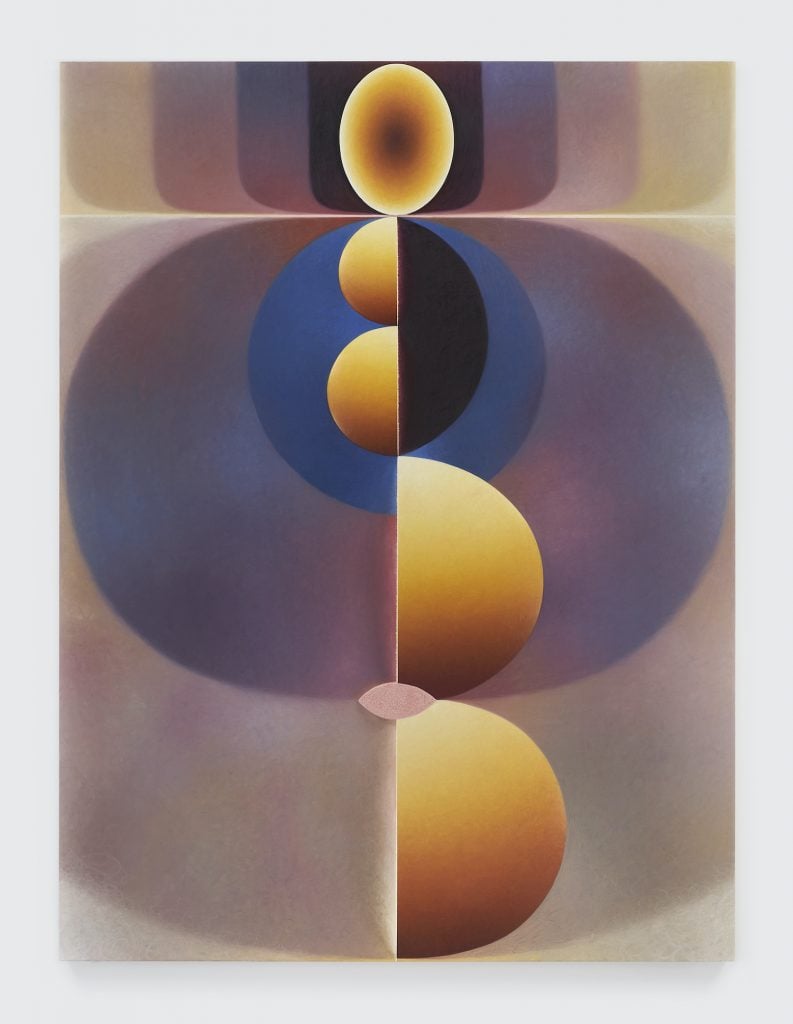

Loie Hollowell, Standing in yellow, pink and blue (2019). Photo: Melissa Goodwin and Robyn Caspare. of Courtesy Pace Gallery.

The second person Johnson told about Hollowell was the prominent philanthropist Fairfax Dorn, who in turn included the young artist’s work in a spring 2016 group show at Ballroom Marfa. The following year, Hollowell was lured away from Feuer/Mesler by Marc Glimcher, Dorn’s husband and the president of Pace. Less than 16 months after she mounted her debut in a Brooklyn apartment, Hollowell had joined one of the world’s most prominent galleries.

“Plumb Line,” Hollowell’s first show after giving birth, helped christen Pace’s new 75,000-square-foot, eight-story building in Chelsea in 2019. The name was a nod to the invisible vertical axis along which Hollowell’s symmetrical compositions are often oriented, but also—according to the gallery—the “gravitational pull experienced during pregnancy.” Each of the exhibition’s nine paintings featured a series of spheres, or half-spheres, which together conjured the curves of an expectant mother. They came with six-figure price tags—a 1,200 percent increase from three years prior—and sold out, just as her work had in every exhibition to date.

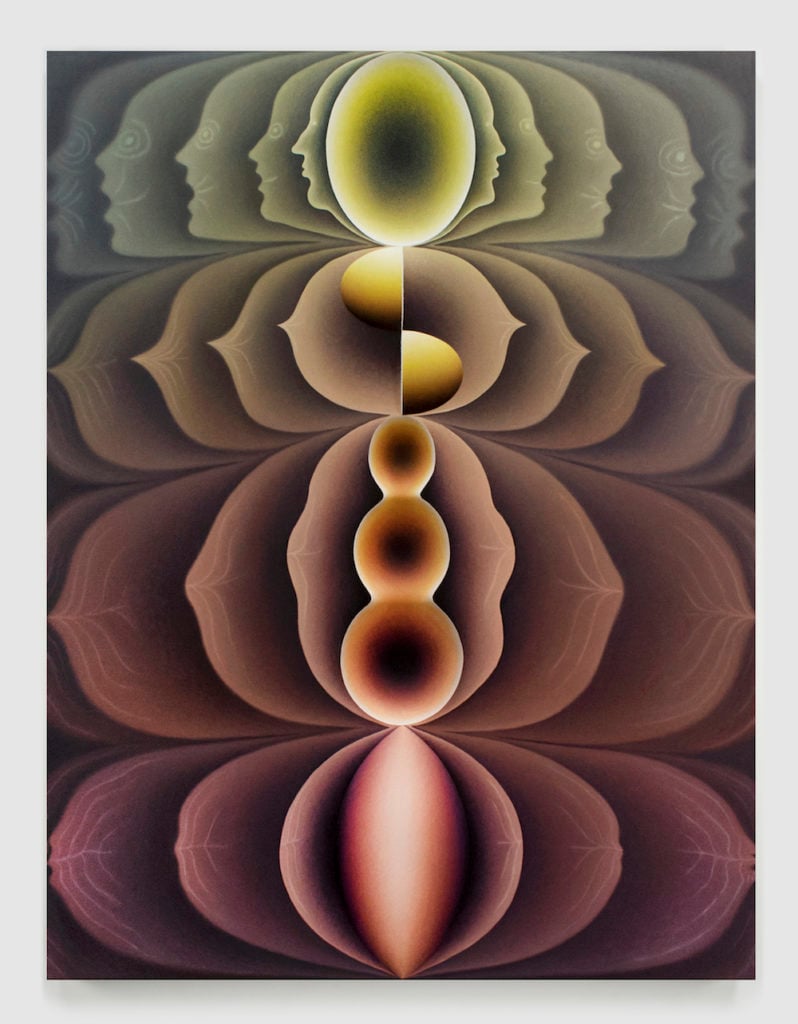

The vertiginousness of Hollowell’s success was compounded by the fact that it seemed to fly in the face of putative art world tastes, then calibrated to expressive figuration and identity-centric portraiture, not spaced-out studies of light and color. The appeal of her art has never been hard to see, though. In Hollowell’s paintings and drawings are echoes of Hilma af Klint’s mystic symbols, Agnes Pelton’s transcendentalist visions, and the radiating shapes of Neo-Tantric painter Ghulam Rasool Santosh. There is a California vibe to much of it, too—trace marks of the state’s yawning topography, a similar sunbaked palette. The Light and Space movement, which coalesced around Los Angeles in the 1960s and ‘70s, looms particularly large: as in the work of Robert Irwin, Helen Pashgian, and other perception-obsessed artists from that loose cohort, Hollowell’s forms appear to glow and float and hum.

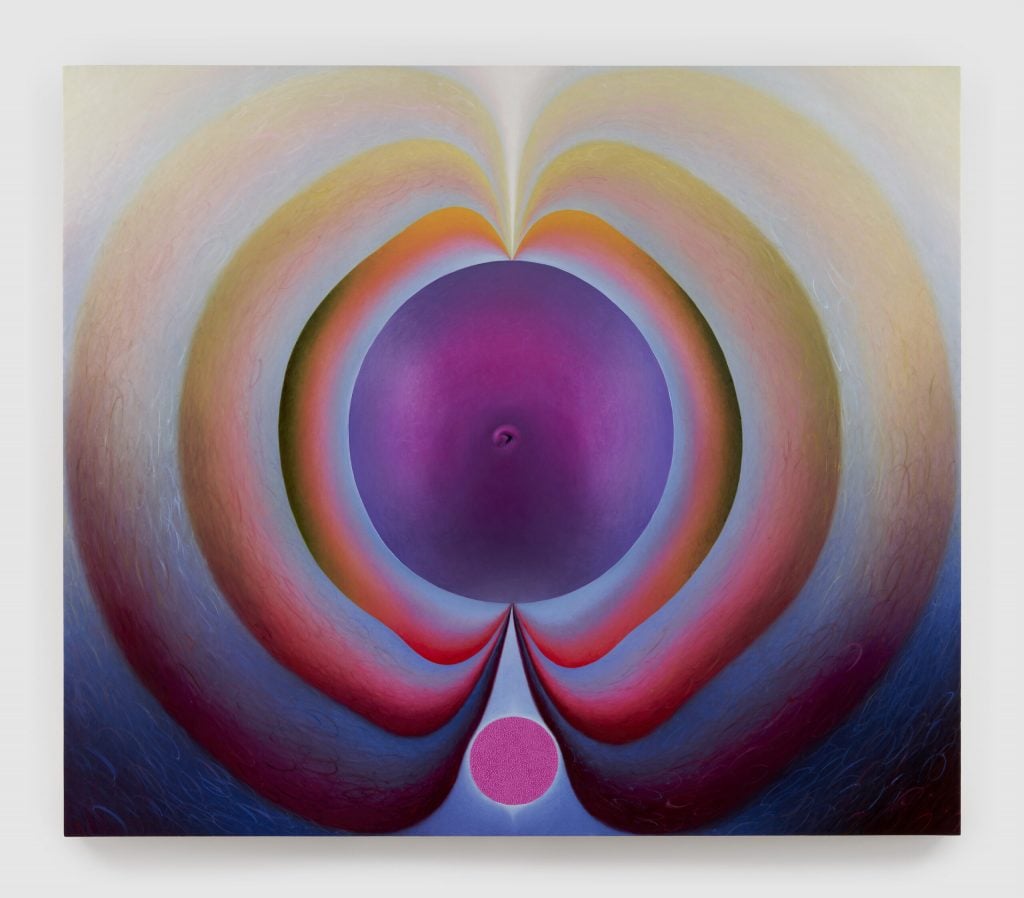

Loie Hollowell, 10pm Feeding – Around the clock (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery. Photo: Melissa Goodwin and Robyn Caspare.

The reach of these references, and Hollowell’s general preoccupation with themes of body and spirit, lend her works a sense of timelessness. And yet, as Aldrich curator Amy Smith-Stewart points out, they are also chocked with other references to time. She points to 10pm Feeding – Around the clock (2022), a pastel drawing included in the survey that substitutes the hourly numerals of a watch face with swollen breasts. The image is reaffirming in its celebration of the biological cycles that unite women, but also a little unsettling—a reminder, in the curator’s words, of “what it’s like for your body to be physically imprisoned by time.”

Like her heroes Georgia O’Keefe and Judy Chicago, Hollowell is less concerned with depicting the female body than capturing the emotions that animate it. Clarity Haynes, a friend and fellow painter, put it well: “She’s interested in the body as it is felt from the inside.”

That’s still the case for Hollowell, though with the inclusion of the cast body parts, she’s grown increasingly interested in the body’s exterior, too. This interest is on full display in the serial paintings that make up the Silverman show. Each is a variation of the same image, wherein gradated waves of paint billow from a resin cast of a friend’s pregnant belly. It looks both like a celestial orb encircled by rings of light and the crowning head of an emergent newborn.

Loie Hollowell, Seven Centimeters Dilated (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Jessica Silverman.

Just as the Aldrich survey shows us where Hollowell’s work has been, “In Transition” points to where it’s headed. But that journey is not paved with one-way roads, the artist reminds. “For me, I have to evolve and experiment, but it doesn’t mean that I’m leaving this kind of abstract color-filled phenomenological work behind. I want to do both of these things, make realist figurative sculpture paintings and super abstract light and space work.”

More than motif, Hollowell’s penchant for symmetry is a metaphor for one of her greatest gifts: balance. You can see it in her sculptural paintings, where she tethers conflicting ideas and allusions together in space, yin and yang; and in life, where she is both—equally—a parent and an artist. “It’s [about] holding two things at once. It’s what you do as a mother. You can love your career, your husband, and your kids all at once,” she said. “If I want to experiment, I just need to do it. And if it fucks up any kind of market then so be it.”

Loie Hollowell, Expanding Figure (2019). Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery.

“Loie Hollowell: In Transition” is on view at Jessica Silverman, 621 Grant Ave, San Francisco, through March 2. “Space Between, A Survey of Ten Years” is on view at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, 258 Main Street, Ridgefield, Connecticut, through August 11.

More Trending Stories:

Art Dealers Christina and Emmanuel Di Donna on Their Special Holiday Rituals

Stefanie Heinze Paints Richly Ambiguous Worlds. Collectors Are Obsessed

Inspector Schachter Uncovers Allegations Regarding the Latest Art World Scandal—And It’s a Doozy

Archaeologists Call Foul on the Purported Discovery of a 27,000-Year-Old Pyramid

The Sprawling Legal Dispute Between Yves Bouvier and Dmitry Rybolovlev Is Finally Over