On View

See Highlights from 101-Year-Old Artist Carmen Herrera’s Long-Overdue Retrospective

The Cuban-American painter gets a well-earned spotlight at the Wexner Center

The Cuban-American painter gets a well-earned spotlight at the Wexner Center

Eileen Kinsella

The Wexner Center for the Arts, in Columbus, Ohio, is the sole venue—after the Whitney Museum—to show the much-lauded retrospective of Cuban-American artist Carmen Herrera, “Lines of Sight” (on view through April 16).

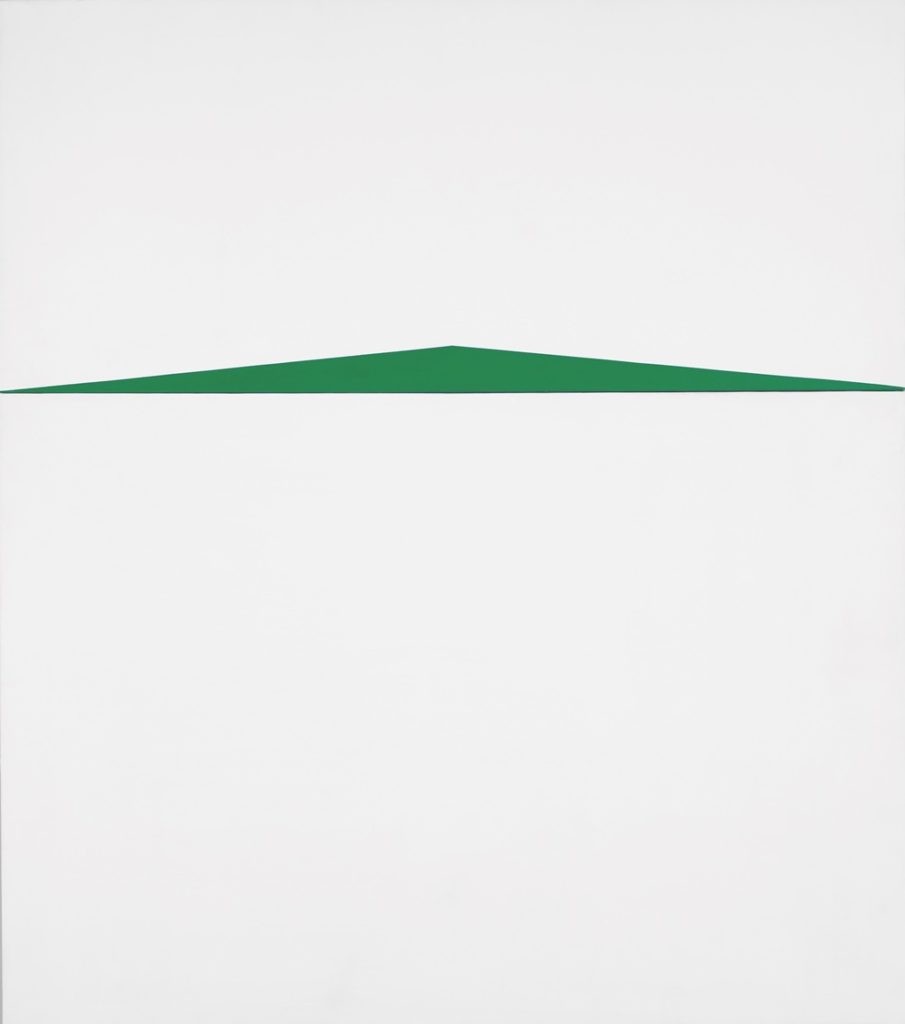

Carmen Herrera, Green and White (1956). Courtesy Ella Fontanals-Cisneros Collection.

Herrera, who turned 101 last May, is world-renowned today, actively creating new work in her New York City apartment to meet demand from collectors and curators alike. But for decades—despite her groundbreaking early exploration of abstraction—she worked in obscurity.

Carmen Herrera, Friday (1978). Courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery.

Thanks in part to the enthusiasm of avid proponents of her work—including longtime Whitney curator Dana Miller (the organizer of “Lines of Sight”) and artist-cum-Museo del Barrio chairman emeritus Tony Bechara, who are holding a talk together at the Wexner Center—that began to change roughly a decade ago.

Installation view of “Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight”, at the Wexner Center for the Arts. Photo by Luke Stettner. © Carmen Herrera.

Now Herrera’s work commands six-figure auction prices and high-profile representation at art fairs. A documentary by Alison Klayman was followed by a sold-out show at the Lisson Gallery this past fall, and the current retrospective has more than cemented her status in art history.

Carmen Herrera, Amarillo Dos (1971). Maria Graciela and Luis Alfonso Oberto Collection

The show consists of about 50 works including drawings, sculpture, and paintings that trace the arc of her career from the years between 1948 to 1978. It was during those decades that she perfected her signature style of abstraction, with the works becoming ever more minimal along the way.

Carmen Herrrera, Blanco y Verde (1959),Whitney Museum of American Art Purchase, with funds from the Painting and Sculpture Committee

Herrera was educated in Havana and in Paris, where she studied art, art history, and architecture. Experts often cite the influence of architecture studies in her geometric-shaped canvases and expertly executed angles.

Installation view of “Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight”, at the Wexner Center for the Arts. Photo by Luke Stettner. © Carmen Herrera.

The exhibition is organized chronologically, beginning with paintings made while she was in Paris from 1948 to 1954. The works reflect the influence of Cubist innovations of the early 20th century in a postwar context. Herrera continued exploring “geometry, space, and the line in increasingly spare and refined compositions as she returned to New York in 1954, when Abstract Expressionism reigned supreme,” according to a curatorial statement for the show.

Installation view of “Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight”, at the Wexner Center for the Arts. Photo by Luke Stettner. © Carmen Herrera.

Also on view are works from the “Blanco y Verde” series (1959–71) and her “Days of the Week” series (1975–78), which reflect her interest in the built environment.

Carmen Herrera, Iberic (1949). Courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery

In Klayman’s engrossing and endearing documentary, “The 100 Years Show,” Herrera says in an interview: “When I was younger, nobody knew I was a painter. Now they’re beginning to know I’m a painter. I waited a long time. There is a saying. If you wait for the bus, the bus will come. I say, yeah. I wait almost a century for the bus to come. And it came!”