People

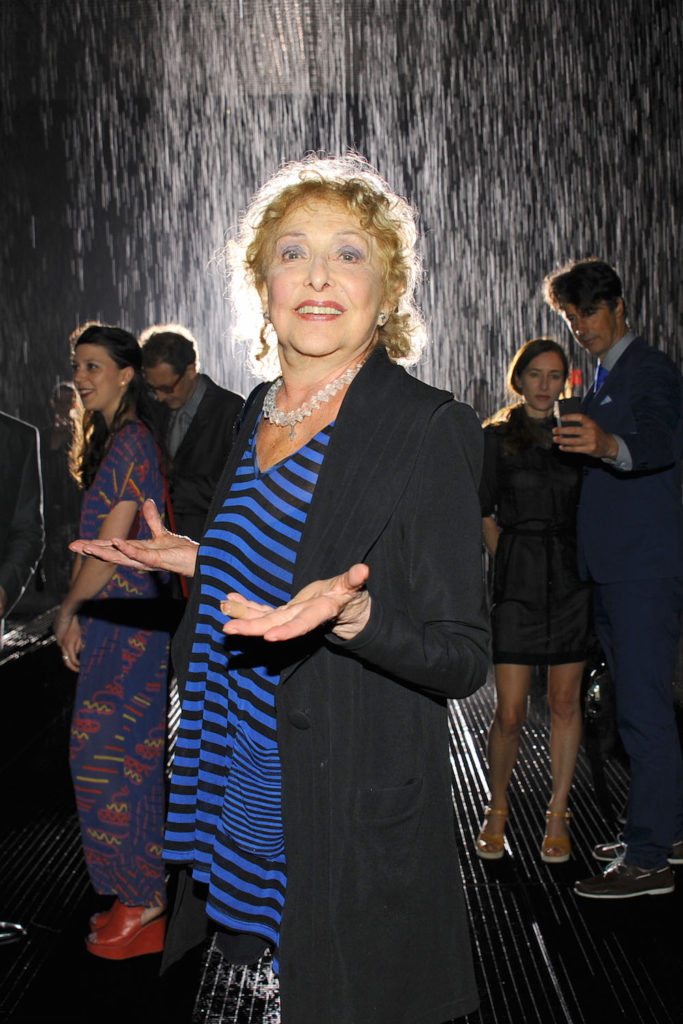

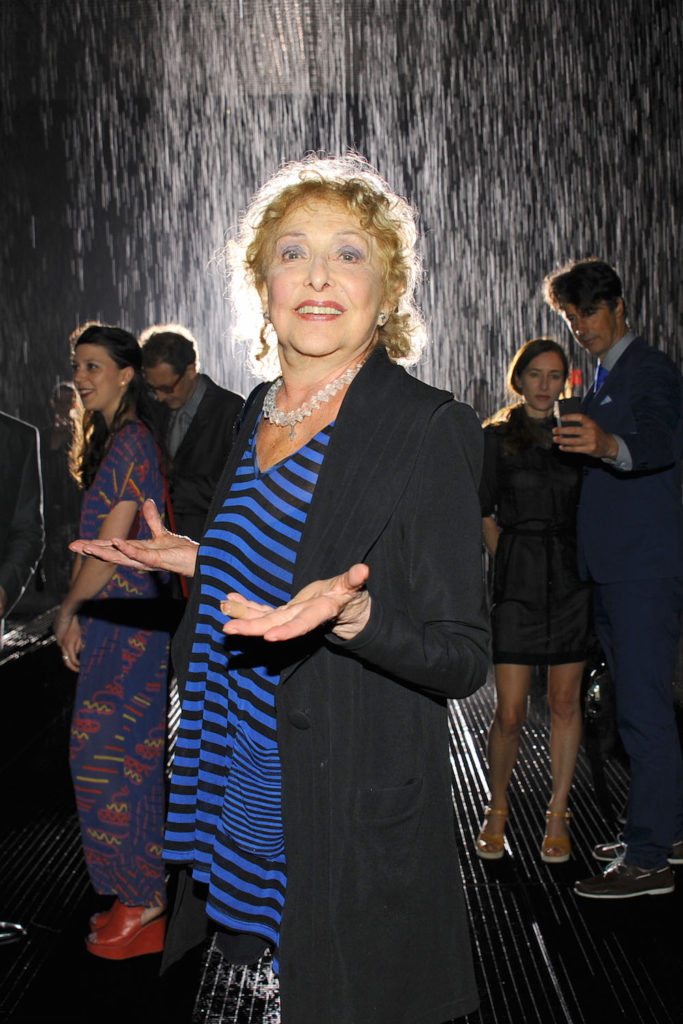

Carolee Schneemann, Feminist Trailblazer Who Redefined the Body as a Site for Art, Has Died at 79

She was known for 'Meat Joy,' 'Interior Scroll,' and a career's worth of work with the body and beyond.

She was known for 'Meat Joy,' 'Interior Scroll,' and a career's worth of work with the body and beyond.

Julia Halperin

Carolee Schneemann, an artist who has inspired generations of creators by using her own body, and the bodies of others, as her medium, has died. She was 79.

New York’s Galerie Lelong, which recently began representing the artist alongside her longtime dealer P.P.O.W., confirmed her death.

Schneemann may be best known for her most sensational works, including Meat Joy, an orgiastic 1964 performance in which scantily clad men and women rolled around with dead fish, sausages, blood, and sundry other substances. Eleven years later, she presented Interior Scroll, a notorious performance in which she unfurled a scroll from her vagina and read aloud the text, which needled a male filmmaker who had criticized the “diaristic indulgence” of her work.

Carolee Schneemann, Meat Joy (1964), Documentation of the performance at the Judson Dance Theater, Judson Memorial Church, New York, US, November 16-18, 1964. Image: Courtesy of C. Schneemann and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York, Photo: Al Giese© Carolee Schneemann, © Bildrecht, Wien, 2015

At the time, some feminist critics slammed the overt sexuality of her work, dismissing her as a narcissist. Leading curators, dealers, and collectors of the day, meanwhile, ignored her almost entirely. “In the 1960s and early ’70s, every gallery rejected my work,” she recently told T Magazine.

But in the 1990s, that began to change. Her first major survey was held at the New Museum in New York in 1996.

(In popular culture, her work helped define the image of performance art: Schneemann was said to be one inspiration for Julianne Moore’s character of Maude Lebowski in the 1998 film The Big Lebowski.)

In more recent years, the full measure of Schneemann’s influence—which informed the work of other artists who explore the limits and the insides of the body, from Marina Abramovic to Matthew Barney—started to come into view.

“To say that Carolee was a visionary is an understatement,” Stuart Comer, MoMA’s chief curator of media and performance art, told the New York Times in 2016. “She is crucial to the way so many artists are working now.”

The following year, Schneemann won the Venice Biennale’s Golden Lion award for lifetime achievement. She was recently the subject of an acclaimed career retrospective, “Carolee Schneemann: Kinetic Painting,” which traveled from the Museum der Moderne Salzburg in Austria to the Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main in Germany and MoMA PS1 in New York.

Schneemann was born in Pennsylvania in 1939. Her father was a doctor, an occupation she said gave her an early introduction to the less idealized, less elegant side of the human body. She began her artistic career as a painter. She got a rocky start when she was expelled from Bard College after painting herself nude.

Carolee Schneemann Early Landscape(1959), Oil on canvas. Image: Courtesy of C. Schneemann and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York

She continued to paint in a style reminiscent of the reigning Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s—and then began to slice and collage her increasingly large paintings. Before long, she was placing herself inside these compositions in a series of photographs called “Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera.”

She became an important figure in the avant-garde downtown New York scene and helped found Judson Dance Theater, the influential company that blurred the lines between everyday movement and dance. In the 1960s and ’70s, she made a number of important films, including Fuses, which depicted her and her husband having sex. (Male critics complained it wasn’t quite pornographic enough when it debuted at Cannes in 1979.)

A group of people looks at the artwork ‘Body Collage’ by Carolee Schneemann from 1967 at the exhibition ‘Carolee Schneemann. Kinetische Malerei’ in Frankfurt/Main, Germany, 30 May 2017. Photo by Andreas Arnold/picture alliance via Getty Images.

Intimacy, the relationship between interior and exterior, and the possibility of communion infused her work. But that’s not to say it was particularly comfortable to experience. The artist Ragnar Kjartansson once described Infinity Kisses (1981–87), a film she made of her and her cat in an extended kissing session, as “the only art piece that has really shocked me.”

At the same time, she also looked outside the body, making a series of significant works about the horrors of Vietnam, including Viet-Flakes (1965), a film that shoots newspaper clippings from above as if from the cockpit of a jet.

Throughout a long career, Schnemann appeared confident that the rest of the world—the art world, the culture—would catch up with her. “I never thought I was shocking,” she told the Guardian. “I say this all the time and it sounds disingenuous, but I always thought, ‘This is something they need. My culture is going to recognize it’s missing something.'”