When Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, the director of Castello di Rivoli in Turin, sat down for an interview with Artnet News recently in the museum cafe, a colleague placed fresh glasses of a specially made cocktail on the table. It is called Aperitivo del Direttore (The Director’s Aperitif), a drink Christov-Bakargiev invented that contains Bergamotto liqueur, prosecco and fresh basil leaves—a more bitter rendition of an Aperol Spritz. Taking a sip of the beverage, the museum leader laid out her similarly unique aspirations for the future of art museums.

“I’d like to invent a new kind of institution that could be a museum of the future,” Christov-Bakargiev said. If art institutions are to survive in the 21st century, she added, they will have to reinvent their missions, and leave behind “an idea from the past” that they are simply guardians of historical art objects. “A museum now is the space where culture meets the world at-large, it is an agent of change,” she said.

Her plans for Castello di Rivoli over the coming year could be seen as a major step to realize her vision. One of the key projects, by the Icelandic-Danish artist Olafur Eliasson, opens on September 21. The artist will transform the museum’s Manica Lunga space into a “major participatory installation” reflecting on the “overdose of digital, screen-based technology,” turning the long, narrow building into “a kind of gymnasium for the eyes and the walking body,” Christov-Bakargiev said.

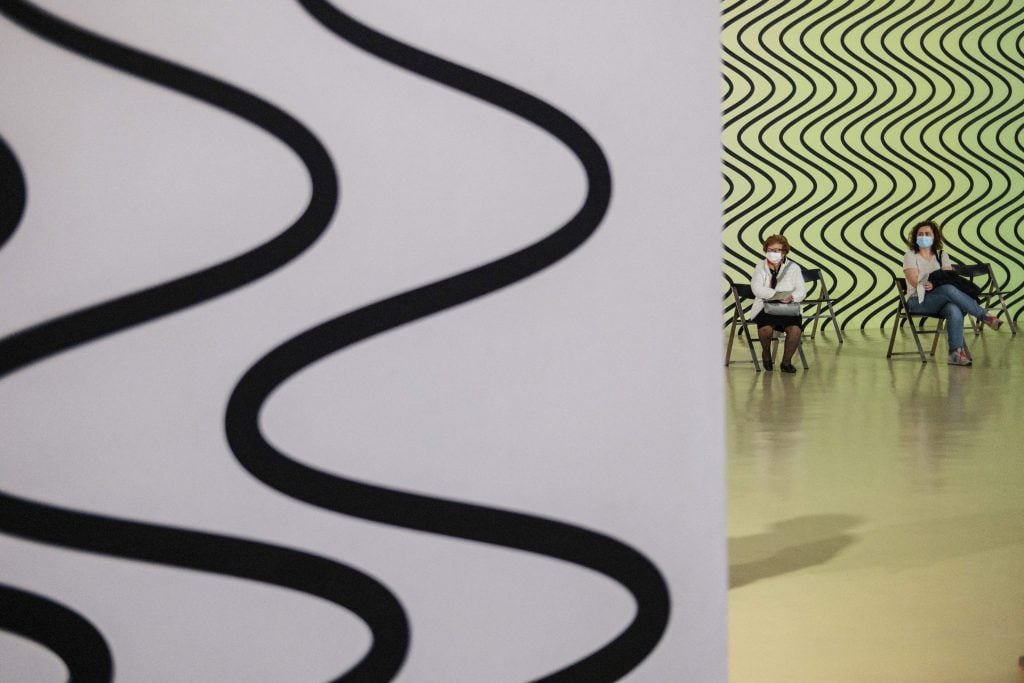

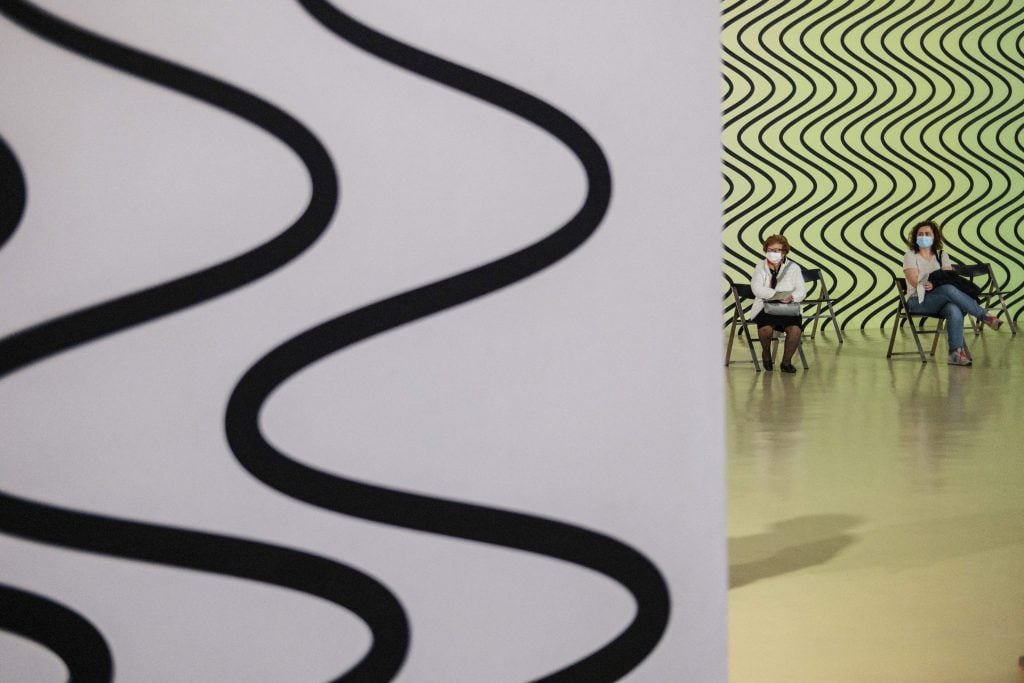

Patients wait to receive a dose of the Moderna Covid-19 vaccine, in the rooms of the Claudia Comte exhibition at the Castello di Rivoli contemporary art museum in Turin, on May 27, 2021. Photo by Marco Bertorello/AFP via Getty Images.

“Olafur has long been interested in art and well-being, the empowerment of the individual through the enhancement of perception, as have I,” Christov-Bakargiev said. “We are convinced that an embodied experience, which heightens our perceptive abilities—a kind of yoga of the senses and the eyes—is extraordinarily important for wellbeing and health.”

Eliasson’s project is an extension of an idea that was first explored last year with L’Arte Cura. The pilot program, organized in partnership with local health authorities, transformed the museum into a vaccination center, with Turin residents receiving their Covid-19 jabs underneath murals by the Swiss artist Claudia Comte, who also worked with composer Egon Elliut to create a soothing soundscape.

“This was an experience of how art can work together with medicine in terms of the future of health programs,” Christov-Bakargiev said. “There needs to be more research about the impact of art on well-being.” The museum director hopes that, in the long-run, museum funds could be raised to support scientific research that could in turn contribute to the development of programs around “new forms of medicine and art.”

The other initiatives that Christov-Bakargiev launched in 2021 have been equally forward-thinking. She was among the first figures from the traditional art world to reach out to the NFT art star Beeple, following his phenomenal Christie’s sale; she has helped save a refugee artist and his family escaping from Afghanistan; and she also launched the 1,200-page catalog of the institution’s famed Cerruti Collection of European art, the fruit of an expansive research project that began in 2017. (Management of the private collection, built by the reclusive, wealthy bookbinder Francesco Federico Cerruti and housed in his villa outside Turin, was given to the Castello di Rivoli after his death in 2015.)

Castello di Rivoli director Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev recorded a virtual tour of the Cerruti Collection in Turin, when the museum was closed during the pandemic. Image courtesy of Castello di Rivoli.

These projects tackled the urgent issues that arise from an ever-changing human condition, Christov-Bakargiev said, and they showed what is possible for the museum of tomorrow.

“It is a question of organizing attention. We are living in an attention economy,” she said. “The digital era is one where we work through symbols. From the smiley face to social media posts, it’s all about the symbols. If you work in art, you can affect the symbolic order quite a lot, and understand the world through the symbolic order.”

Such topics will be further explored during the second part of “Espressioni,” a group show that looks at the history of expressionism through Modern and contemporary art, running from April 13 to July 17. New projects and commissions for the exhibition include a work by the Australian Indigenous artist Richard Bell, with whom Christov-Bakargiev worked when she served as the artistic director for the Sydney Biennial 2008, as well as a collaboration with the Turner Prize-nominated artist collective Cooking Sections.

The programme for 2022 also includes projects by performer and actor Silvia Calderoni; Turin-based filmmaker Irene Dionisio; as well as Lina Lapelyté, a co-creator of Sun and Sea (Marina), the Golden Lion-winning installation and opera performance for the Lithuanian pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale.

“Museums and art have a really important role to play in the 21st century,” Christov-Bakargiev said. “Make them a place of active engagement with the world. A museum of contemporary art is no longer a museum of visual art anymore.”

“I would really like to try to reinvent those categories,” she added, “to see how we can make another structure of museum that is not just for art, literature, music—not even for human culture only, but also for non-human culture.”