People

For Artist Cassi Namoda, Whose Work Blends African Histories and Mythologies With Personal Memories, ‘Painting Is a Spiritual Act’

The Mozambique-born, US-based artist just wrapped a solo show at Goodman Gallery in Cape Town.

The Mozambique-born, US-based artist just wrapped a solo show at Goodman Gallery in Cape Town.

Helen Jennings

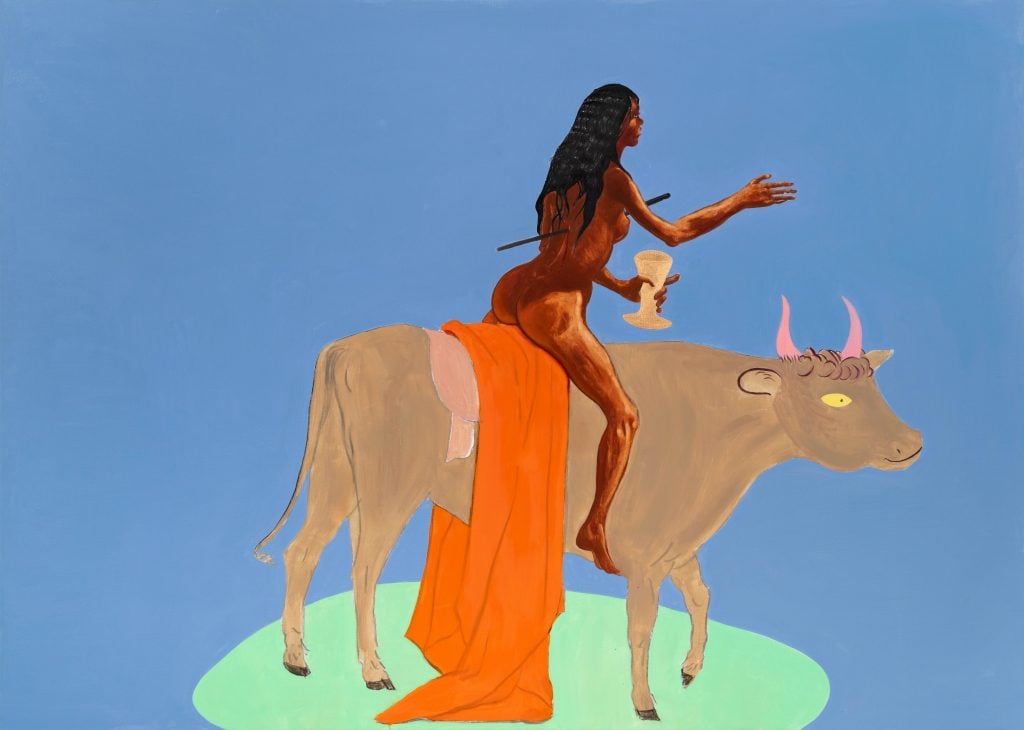

In Cassi Namoda’s 2022 painting, Heartbreak takes new forms, a regal, naked woman sits astride a gentle cow with pink horns on its head and a swathe of orange fabric across its back. The woman holds an empty goblet in one hand, the other hand raised and pointing the way forward. Yet piercing her chest is a black spear, which begs the question: Is she the hunter or the hunted?

Such surreal landscapes and allusive figures abound in the artist’s alluring work, which situate the viewer in a post-colonial, African space where dense histories and mythologies intertwine with her personal memories and imaginings.

Namoda’s appreciation for the art canon and traditions of symbolism is apparent, yet her vivid colors and bold oil and acrylic brushstrokes feel instinctual. Ultimately, it’s her ability to conjure up hybrid narratives that are at once wondrous and poignant, everyday and fantastical, archival and current, immediate and ambiguous, uplifting and painful, that has marked this young artist as one to watch.

Cassi Namoda, Heartbreak takes new forms (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery.

“Painting is a spiritual act,” said Namoda on a call from her Manhattan apartment. Just one of her bases, she divides her time between New York City, a studio in East Hampton, and her new home in the Berkshires. “There is a sense of unknowingness when I’m working on a painting. There’s a spirituality to leaving it up to the universe to guide you and trusting that it’ll all come together.”

This poetic embrace of uncertainty stems from her peripatetic upbringing. Born in Maputo in 1988 to a Mozambican mother and an American father, the family lived in Indonesia, Kenya, Dominican Republic, Benin, and Uganda all before she completed high school. Namoda went on to briefly study cinematography at the Academy of Arts in San Francisco before returning to Mozambique in her early 20s, and then on to New York, where she worked with fashion designer Maryam Nassir Zadeh. In 2016 she landed in Los Angeles and turned wholeheartedly toward painting.

“I didn’t grow up with parents who took me to museums. They took me to nature,” Namoda said. “So, after school, my experiences of fashion, culture, and art dovetailed into my learnings in Africa. Moving around a lot and having a large curiosity has been very prevalent in my life, and still is.”

Cassi Namoda, Life has become a foreign language (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery.

In the past five years, the artist has enjoyed several impressive solo exhibitions, and her work is now in the public collections at Pérez Art Museum Miami, Baltimore Museum of Art, MACAAL in Marrakesh, and the Studio Museum in Harlem. Her recently concluded solo show, “Life Has Become a Foreign Language” at Goodman Gallery in Cape Town, completely sold out (prices for her works range from $35,000 to $55,000).

Liza Essers, owner and director of Goodman—which represents Namoda alongside Xavier Hufkens in Brussels and François Ghebaly Gallery in Los Angeles and New York—believes the artist’s nomadic outlook sets her apart. “Cassi brings so many nuances to the discourse around colonial history and identity politics, which results in a universal sensibility,” Essers said. “And as a person, she’s also just the most incredible light with a beautiful soul and energy.”

Natasha Becker, curator of African Art at the de Young Museum, San Francisco, has invited Namoda to present a solo with Goodman in Tomorrows/Today, a curated section of Investec Cape Town Art Fair 2023 highlighting promising talents. She’s as drawn to the artist’s dreamlike sensibility as she is to her rigorous intellectual thinking.

Cassi Namoda, Condemned to perpetual earth II (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery.

“Cassi’s paintings conjure up unexpected feelings, memories, and senses of time, things that you can’t quite put your finger on but you feel on a sensorial and sensual level,” Becker said. “But beyond this immediate, myth-like visual experience, she’s also making cognitive connections and producing new knowledge that goes beyond traditional frames of painting.”

Equally impressed is Osei Bonsu, curator of international art at Tate Modern, who includes Namoda in his forthcoming book, African Art Now (Ilex Press/Tate). He explained, “Mozambique has a strong artistic lineage dating back to Bertina Lopes, Malangatana Ngwenya, and Ernesto Shikhani, who pioneered their own form of Modernism and political resistance at a time of colonial occupation. Cassi refers back to some of those histories while also building it out into something much more pan-African and contemporary.”

Namoda’s themes draw from a constellation of preoccupations. Literary influences range from Christian theologian John Mbiti (“He wrote that East African societies believe God exists everywhere—it’s spiritual and animistic.”) to the Négritude traditions of Léopold Senghor, Aimé Césaire, and Édouard Glissant, as well as lesser-hailed Lusophone writers such as Mia Couto and Luís Bernardo Honwana. Meanwhile, her love of film is reflected in the cinematic quality of her paintings. “I think about directors like Ousmane Sembène or Djibril Diop Mambéty, and the way the image holds such weight before dialogue is even expressed,” she said.

Cassi Namoda, Depressed in the tropics II, from “Tropical Depression.” Courtesy of the artist and Xavier Hufkens.

And then there is her interest in upending the work of Matisse, Picasso, Cézanne, and Gauguin: “I like this idea of making work that I would consider ‘African Expressionism.’ It’s like I am taking agency over the idea of European painters that were inspired by African aesthetics.”

The artist prefers to forgo the comfort of a white-walled studio in favor of more challenging environments, recounting adventures such as working out of an abandoned building in Oaxaca. Her spring 2022 show at Xavier Hufkens, “Tropical Depression,” was completed in her mother’s village while Namoda was suffering from illness and with her materials stuck in customs. All this fed into the work. “There’s now a constantly looming threat of cyclones in Mozambique,” she noted. “’Tropical Depression’ is what you call a cyclone, so I explored all the metaphors within that, as well as what I was dealing with internally in my family.”

Drawing on photojournalist Ricardo Rangel’s images of nightlife in 1960s and ’70s Maputo, the show brought Namoda’s recurring women characters, the Marias, to the foreground. “Before the Marias were metaphoric, but here they were large scale, womanly figures,” the artist explained. “Their gaze was very visceral but off to the side. They were stuck in some sort of trauma. I was interested in how body language can make a painting uncomfortable, and that resulted in a very corporeal body of work.”

Cassi Namoda, Self loathing in 100 percent humidity, from “Tropical Depression.” Courtesy of the artist and Xavier Hufkens.

Looking forward to fall 2023, Namoda will bring a solo to Goodman in London that delves into Mbiti’s writings on Sasha and Zamani. These Swahili spirits and aspects of time will be visualized by the artist as women figures. “Sasha are known by someone still alive and are concerned with the present time, the recent past, and the near future. While Zamani are not known by anyone currently alive. Zamani is the limitless past,” Namoda said. “I’m interested in these non-linear and spiritual notions of time that are apart from western thinking.”

Beyond art, Namoda has lent her hand to a number of collaborations, among them J. Crew clothing, Linda Sivrican perfume, Marimekko textiles, and Catbird jewelry. Other projects have included painting a 2020 cover of Vogue Italia and developing Saudade, a Mozambican black tea project.

“I am a dynamic human, and life is very interesting, so I want to engage with it all,” she said. “Whatever is sincere to me, I will want to do it, and do it well.” All of this speaks to her down-to-earth personal style: “My mother taught me that you look well put together when you’re a reflection of your environment. If I’m standing on soil, I’m in Blundstone boots and if I’m in the city, I’m wearing nice loafers.”

The artist at home. Photo: Andrés Altamirano.

Namoda’s next escapade, the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation residency program, falls into the former category, with the coming months taking her to its three rural locations in Southern Ireland, Senegal, and Connecticut, where she’ll indulge in plein-air painting. And after that, who knows where her unbridled creativity will take her.

“I love freedom, I love authenticity of self, I love constantly evolving. That’s the healthy ego. If I love what I do and it feels real to me, then I’m good,” she said. “As a young woman of color, I’ve had so much white masculinity to deal with, but I stayed true to myself—and most of the time, I was right.”

Namoda’s advice to those who aspire to follow in her well-shod footsteps? “Strive to be curious, to be open, and to embrace yourself. I always say, when you know what you’re doing, you can do what you want. That’s it. You don’t have to worry about anything else.”