Art World

A New Particle Accelerator Will Help Identify Art Forgeries, Because Science

Could this be the latest in art authentication?

Could this be the latest in art authentication?

Sarah Cascone

Imagine a machine that could identify the materials in a work of art in mere hours, determining when it was made, identifying modern-day forgeries, or even, in the case of metal jewelry, what mine a piece originally came from.

Such technology is currently in the works at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, which has successfully developed a miniaturized accelerator, capable of smashing protons together at light speed to determine what particles are made of—providing key information to art authenticators looking to spot forgeries made from anachronistic materials.

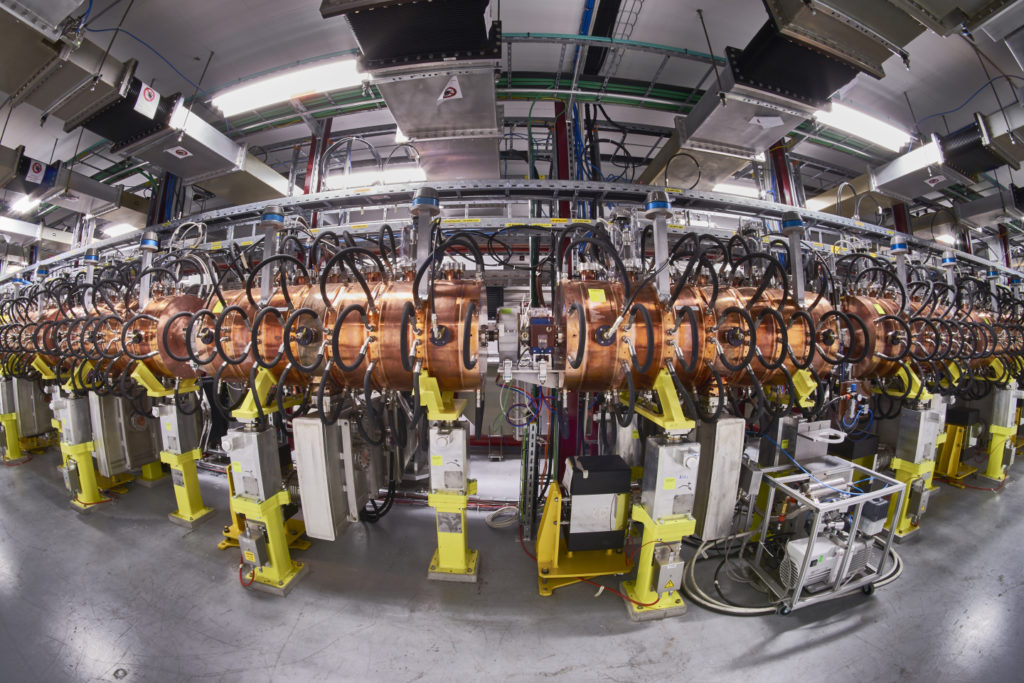

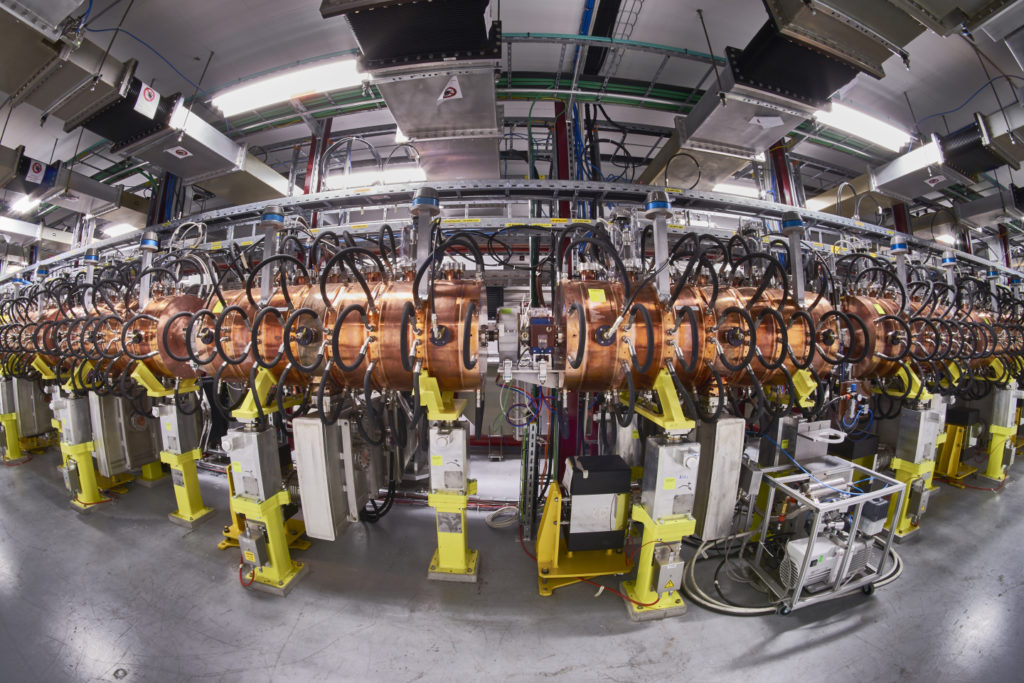

Over the last decade, CERN has spent 93 million Swiss francs ($93 million) on the new Linac 4 machine, a 295-foot-long injector that produces the particles for the 17-mile long Large Hadron Collider (LHC). Unveiled on May 9, it replaces the current injector, which is 39 years old.

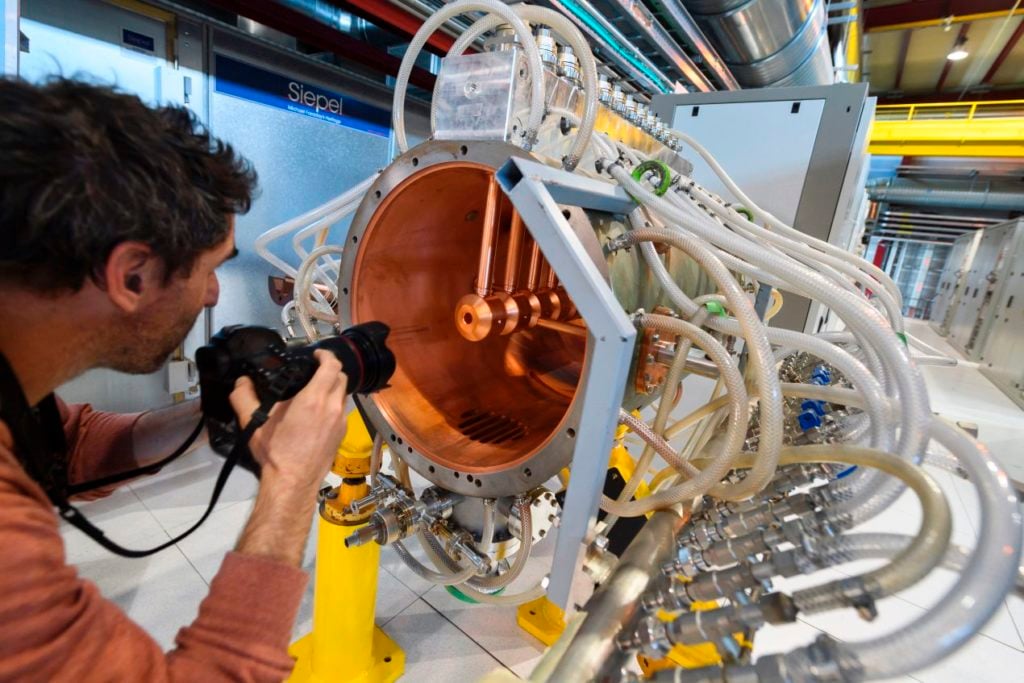

A photographer takes a picture of a prototype of the tube of the new linear accelerator Linac 4, at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) on May 9, 2017 in Meyrin near Geneva. Courtesy of Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/Getty Images.

There is already a portable version of the machine being used to help doctors treat cancer patients. Doctors can use isotopes, which decay rapidly, to help diagnose cancers. Having a particle accelerator on site at a hospital eliminates the challenges of transporting unstable isotopes. Currently, CERN is hard at work creating an even smaller version for art museums.

“We already have a collaboration with the Louvre, and with the Italians at Florence at the Italian institute for conservation of artworks,” project leader Maurizio Vretenar told Reuters. He hopes to develop a 220-pound, three-foot-long portable accelerator that could help identify the materials in an art piece without the risk of damaging it. (The Louvre is currently the world’s only art museum with an in-house particle accelerator.)

It should come as no surprise that CERN is quick to explore the arts applications of its accelerator technology. Through its arts and science program Arts at CERN, the organization has a history of supporting artists whose work exists at the intersection of art and technology. (CERN was also responsible for uploading the first photograph to the internet.) Last month, CERN announced its 2017 artists in residence: Laura Couto Rosado, Cheolwon Chang, Tomo Savić-Gecan, and studio hrm199, led by artist Haroon Mirza.

Haroon Mirza, Adam, Eve, Others and a UFO (2013). Courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery 1

The organization has been partnering with international cultural organizations on artist residencies since 2011, and introduced the COLLIDE International Residency Award, in collaboration with Foundation for Art and Creative Technology (FACT) in Liverpool, in 2016.

South Korean artist Yunchul Kim was the first honoree, and entries are currently open for the second edition of the award, a fully-funded, three-month residency split between the two organizations that allows the artist to partner with a CERN scientist.