Art World

Scientists Uncover Pablo Picasso’s Chemical Fingerprint in Breakthrough Study

The data could help detect forgeries.

The data could help detect forgeries.

Henri Neuendorf

An extensive analysis of Pablo Picasso’s early work by a Spanish chemical engineer has provided some fascinating insights into the artist’s paintings created between 1895 and 1900.

Using cutting-edge, non-invasive technology, chemical engineer Dr José Francisco García Martínez of the University of Barcelona, in collaboration with the Museu Picasso, Barcelona analyzed works from the artist’s early period, prior to the advent of Cubism.

“We didn’t work invasively, only with light. Spectrometry is a proven and long-used method, but the analytical equipment, up to now, did not allow us to examine large objects such as a work of art,” Garcia Martinez told Der Standard in an interview.

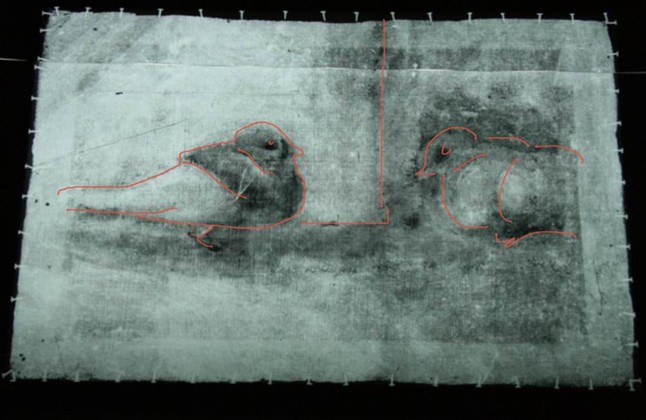

Analysis showed that Man With a Basque Hat (1895) was painted on a used canvas depicting pigeons.

Photo: Museu Picasso/ Universitat de Barcelona

“It is similar to space research, whereby the chemical composition of far-away planets is analyzed based on the light they reflect,” he explained. “Reflectometry in the infrared region provides an insight into its layers and its composition.”

The study not only reveals information about the composition of the artist’s early work—which will be of great interest for art historians—but also provides what García Martínez calls “a chemical fingerprint of the young Picasso’s process,” which could prove to be invaluable for authentication and the detection of fakes.

“This chemical fingerprint is unique to the painter and allows us to characterize him. It is not only about the materials used but also about traces, which for example give us clues about where Picasso bought his pigments. This is a solid scientific basis for research,” García Martínez explained.

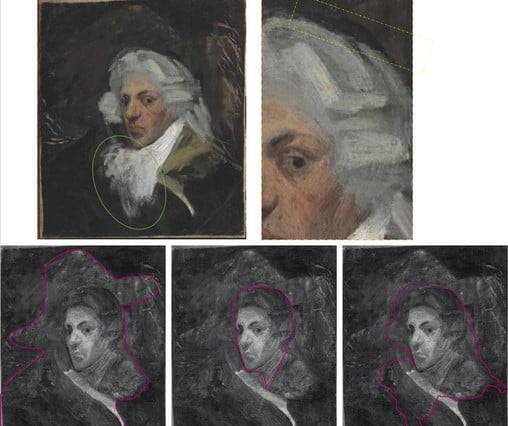

X-rays of Picasso’s Self Portrait With Wig (1990) shows the artwork previously depicted a man wearing a large hat.

Photo: Museu Picasso/ Universitat de Barcelona

While compiling data for the artist’s chemical fingerprint, García Martínez’s team made some breakthrough discoveries. Not only are they the first to analytically detect the pigments used by Picasso during his early period, they also analyzed the primers with which he prepared his canvasses. “This is of particular interest to me as a chemist, and also more generally for the professional world,” he added.

Despite the important findings, the chemical engineer said there’s still work to be done. “That’s the way it is in science. When you answer a question, the answer raises even more questions,” he said.

The chemical fingerprint isn’t the only science-based authentication system that’s helping the art world tackle fraud. In October, scientists developed a unique synthetic DNA tagging system for artworks with the aim of preventing forgery.