Auction house Christie’s and top antiquities collector and hedge fund manager Michael Steinhardt are mounting a vigorous defense in their ongoing legal battle with the Republic of Turkey over a multimillion-dollar, 5,000-year-old antiquity known as the Guennol Stargazer.

On August 28, Christie’s and Steinhardt filed a 27-page motion to dismiss the case in US District Court, complete with a detailed graphic timeline showing that the antiquity had been in the US for more than five decades before Turkey made an effort to recover it. Any claim, they argue, would therefore be outside the statute of limitations.

Turkey has said that the object—which came to its immediate attention when Steinhardt consigned it for auction in April—was illegally excavated. Each individual in the provenance chain, it argues, “knew or should have known at that time that the idol had been looted from Turkey.”

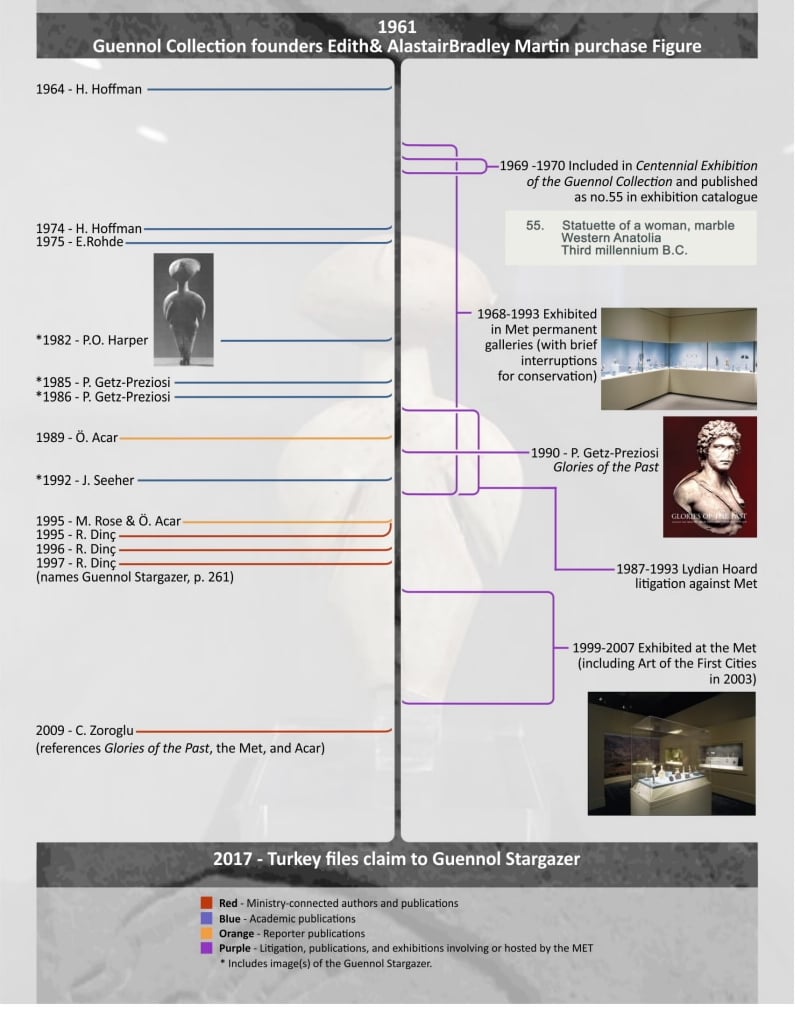

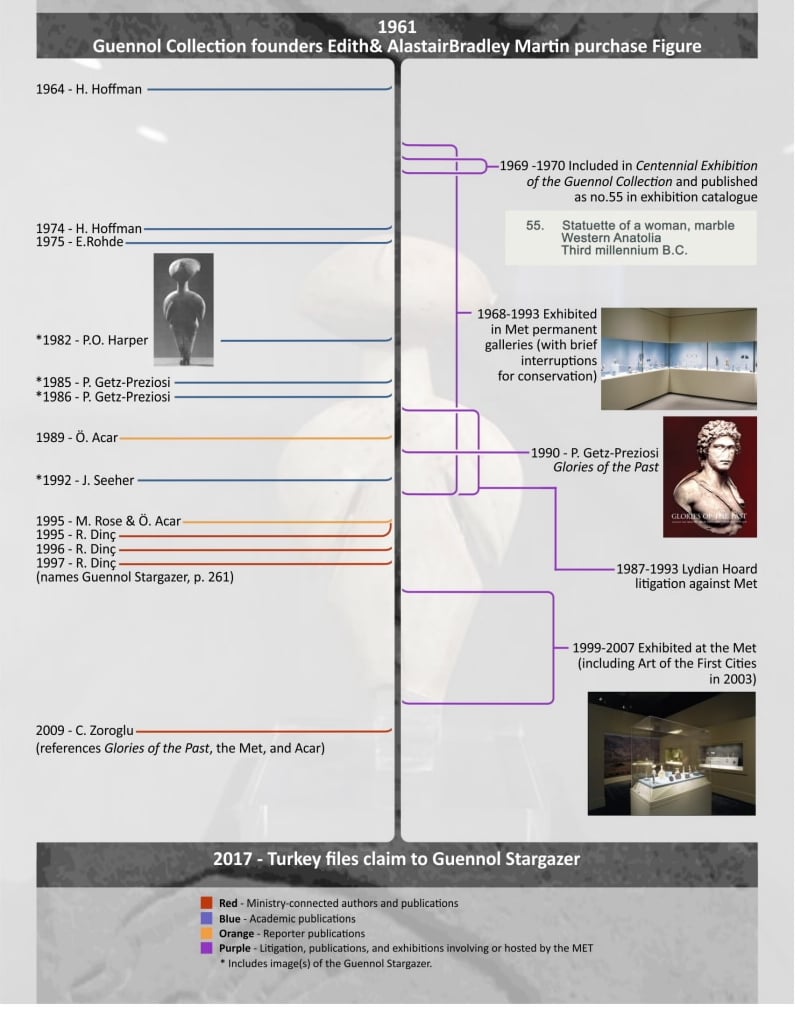

A pictorial timeline illustrating the location of the Stargazer, between 1961–2017

In the new filing, the defendants argue that Turkey, too, should have been paying closer attention. “Turkey knew the Guennol Stargazer was in New York by 1997—twenty years ago—and possibly earlier, and had all the information it needed to make a claim of ownership, or at the very least, to inquire.”

The auction house points out that since the idol’s arrival in the US, it has been referenced more than eight times in museum catalogues and academic publications. It was also displayed for lengthy periods at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The timeline attached as an exhibit to their motion even breaks out instances where specific publications involved authors connected to the Turkish ministry.

For its part, Turkey has argued that it cannot reasonably be expected to find every stolen object taken out of the country illicitly the moment it surfaces in a book or at a museum.

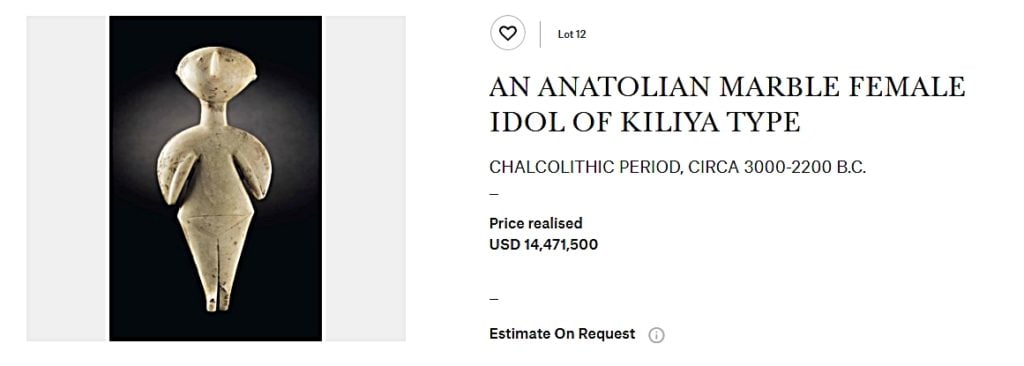

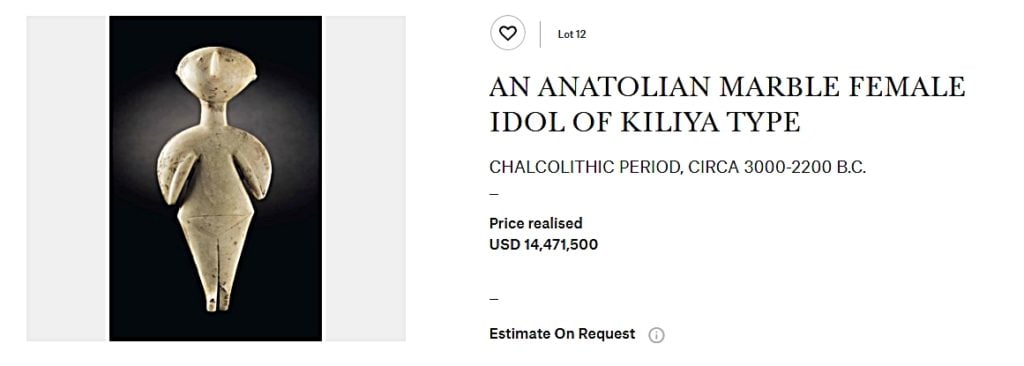

Screenshot from Christie’s New York “The Exceptional Sale,” April 2017. Image via Christie’s.

A spokesperson for Christie’s said in an email to artnet News: “We can confirm that Christie’s filed a motion to dismiss based on new research that refutes the plaintiff’s main assertions. While Christie’s takes very seriously all issues related to cultural property rights, we have clearly established that this object’s whereabouts have been well documented outside of Turkey for the last 50 years, and well known to Turkish cultural authorities for at least the last 20 years.”

As artnet News reported last month, a judge ruled that Christie’s was required to identify the final bidder of the unconsummated sale—the person bid $12 million but then walked away—reasoning that the potential buyer “might have information about the idol, about the bidding process, or about Christie’s vigilance in determining the provenance of the idol.”

The bidder was, in fact, subsequently identified, though a protective order was put in place so only the lawyers know his or her identity.

The Stargazer dates from approximately 3,000 to 2,200 BC. The earliest provenance information stretches back to 1961, according to the dismissal papers, when the New York collectors Edith and Alastair Bradley Martin acquired the figure for their Guennol Collection. It subsequently passed through the hands of multiple collectors before Steinhardt bought it in 1993.

Turkey’s amended complaint for the idol was filed in late July. Frank Lord, the attorney for the Republic of Turkey, told artnet News: “We cannot comment on motions while they are pending. Defendants’ motion was not unexpected, and our client will file an appropriate response with the Court.”

Christie’s is arguing that the claim could set a troubling precedent for collectors and institutions. In the latest filing, it writes: “Turkey’s view that it cannot act on all of its lost objects [and] is therefore justified in sitting on knowable and even known claims and then pursue them at its pleasure and convenience, is inconsistent with New York law and would set a disastrous precedent for collectors, museums and the art market.”