Law & Politics

A Hedge Fund Titan Triumphs Over the Nation of Turkey in the Legal Fight Over a Multimillion-Dollar Ancient ‘Stargazer’ Idol

The judge determined that financier Michael Steinhardt is the idol's rightful owner.

The judge determined that financier Michael Steinhardt is the idol's rightful owner.

Eileen Kinsella

A federal judge has ended a years-long legal saga concerning the ownership of an antiquity known as the “Guennol Stargazer,” which originated in what is now Turkey but ended up in private hands in the United States.

An emphatic 25-page ruling issued by District Judge Alison Nathan on September 7 ends Turkey’s quest to reclaim the sculpture. Nathan determined that the prominent antiquities collector and hedge-fund founder Michael Steinhardt is the rightful owner of the object, which for years was on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The case stretches back to 2017, when Steinhardt consigned the sculpture to Christie’s for sale. That’s when Turkish authorities claimed they first became aware of the object, which they contended was illegally excavated. (At Christie’s, it sold for $14.5 million before the buyer reneged, citing the lawsuit.)

Before long, Turkey began aggressively pursuing a variety of legal avenues to reclaim the sculpture, including suing Christie’s. Each individual in the provenance chain, Turkey argued, “knew or should have known at that time that the idol had been looted from Turkey.” Christie’s and Steinhardt both countersued, claiming Turkey had wrongfully interfered with their business dealings.

In her recent ruling, Judge Nathan concluded that Turkey’s attempts amount to too little, too late. The country “did not meet its burden of proof in establishing ownership of the idol”—and, she added, “even if Turkey had established ownership, the trial record readily establishes that Turkey slept on its rights, which bars recovery.”

Attorneys of Steinhardt, Christies, and the Republic of Turkey did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

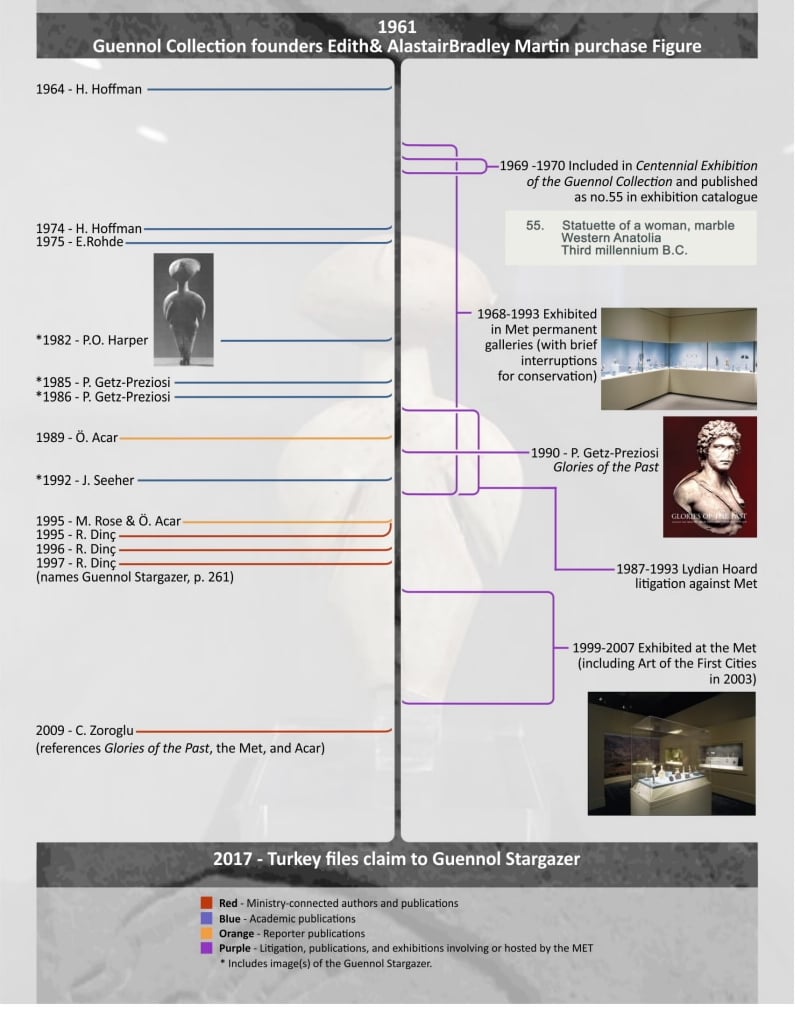

A pictorial timeline illustrating the location of the Stargazer, between 1961–2017

To determine exactly who owned the idol, the court conducted an eight-day bench trial in April, which prompted Nathan’s most recent ruling. The judge did not disagree with Turkey that the object was “likely manufactured in the middle or late 5th millennium B.C.E., between 4800 and 4100 B.C.E, in Kulaksizlar, which is located in modern-day Turkey’s Manisa Province.” But, she wrote, “where the idol traveled to after its manufacture is more of a mystery.” Specifically, it is impossible to prove that the idol was exported after 1906, which would have given Turkey the right to reclaim it.

The idol emerged in New York in 1961, when J.J. Klejman, an art dealer, sold it to New York collectors Alastair and Edith Martin. The Martins owned the Idol for the next 22 years, and it formed a part of their famous “Guennol Collection.”

It passed through their heirs to the Merrin Gallery, where Steinhardt and his wife, Judy, acquired it in 1993.

At trial, Steinhardt “testified credibly about the circumstances surrounding his acquisition of the Idol,” Nathan wrote.

In the end, the judge determined, Turkey ought to have realized the idol’s whereabouts in the United States long before Steinhardt sought to sell it in 2017. The idol “was widely discussed in the literature starting in the 1960s, and it was in near-constant display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for decades.” Furthermore, she noted, the idol was discussed in Turkish publications as early as the 1980s and early 1990s.