Christo, the Bulgarian artist who captivated audiences around the world for more than five decades with massive public art installations, has died. A representative from the artist’s studio said he was at his home in New York City when he died of natural causes earlier today.

“Christo lived his life to the fullest, not only dreaming up what seemed impossible but realizing it,” read a statement from the studio. Together with his late wife and collaborator, Jeanne-Claude, Christo created artwork that “brought people together in shared experiences across the globe, and their work lives on in our hearts and memories.”

Over the years, Christo brought his ambitious visions for monumental art to sites as far-flung as the Australian coastline and the German parliament, always looking to spark the public’s imagination and inspire them to engage with their surroundings differently. His career was defined by his decision to largely abandon the traditional gallery space, opting instead to drape curtains across valleys and weave fabric around bridges. He had the vision and ambition of an artist, the exactitude and specificity of an engineer, and a level of grit, determination, and pushiness that few could match.

Together, he and Jeanne-Claude wrapped the Pont Neuf in Paris and the Reichstag in Berlin; they installed 7,503 gates with saffron-colored nylon panels in Central Park; and they surrounded 11 islands in Biscayne Bay, Miami, with Pepto-Bismol-colored fabric. He often liked to remind people that these temporary, magical interventions were the products of sometimes decades of unglamorous work. While he and Jeanne-Claude completed 23 projects together over 50 years, they were unable to realize 47 more.

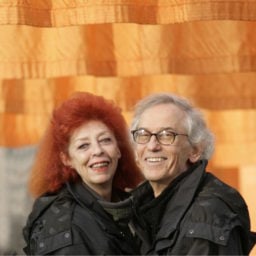

Christo and Jeanne-Claude during the work of art The Gates, Central Park, New York (2005). Photo by Wolfgang Volz, ©Christo, 2005.

After his wife died of a brain aneurysm in 2009, Christo continued working to shift that ratio. One of their long-gestating plans—to wrap the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, originally proposed in 1962—was nearing completion just before his death. L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped is due to be realized in September 2021, after a year-long delay caused by the ongoing public-health situation. Christo’s studio confirmed that the project “is still on track,” noting that the duo “have always made clear that their artworks in progress be continued after their deaths.”

Christo Vladimirov Javacheff was born in Gabrovo, Bulgaria, in 1935. He studied at the country’s National Academy of Art before fleeing its communist government, smuggling himself in a freight car headed to western Europe. After stints in Vienna and Switzerland, he arrived in Paris in 1958, where he made a living painting portraits of socialites while making small wrapped objects with fabric and twine in private.

His trajectory shifted when he met Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon, who helped him realize more ambitious projects outside the gallery and studio space. In 1961, the duo created their first temporary outdoor environmental work of art, a pile of stacked oil barrels and rolls of industrial paper covered in tarp installed in Cologne’s harbor. The resulting sculpture seemed to humanize the piles, as if they were very conspicuously trying to make themselves invisible by covering themselves with a sheet.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Dockside Packages, Cologne Harbor (1961). Photo: Stefan Wewerka. © 1961 Christo.

In an interview with Artnet News published in March, Christo said that many of his projects were defined by the experience of being a nomad and a refugee. “The cloth is the principal element to translate this,” he said. “The projects have many sturdy parts, but the fabric is very fast to install, like the tents of Bedouins in nomadic tribes.”

His reputation grew when he and Jeanne-Claude illegally blocked the rue Visconti in Paris in 1962 with Wall of Oil Barrels—The Iron Curtain, a wall of 89 oil barrels piled 14 feet high, to protest against the construction of the Berlin Wall. This project, as well as the others created during the formative years the couple spent together in the City of Lights, will be the subject of a forthcoming (though currently postponed) exhibition at the Centre Pompidou.

The pair’s projects became even grander still after they moved to New York in 1964. Decades later, The Gates, which was installed in Central Park in 2005 and which former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg called “one of the most exciting public art projects ever put on anywhere in the world,” made them famous beyond the confines of the art world.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, documentary photograph of Surrounded Islands Biscayne Bay, Greater Miami, Florida (1980–83). Photo: Wolfgang Volz © Christo 1983.

Although Christo was sometimes associated with such movements as New Realism and Land Art, he preferred not to be tied to any broader group, or even a particular medium. (Unforgettably, he was the only person who chose himself when asked by Artnet News in 2017 to name the most influential artist of the past century.) For him, the definition of art was expansive. The particulars of the fabric he used—where it was manufactured, the thread count, the history of the hue—were as important as the bureaucratic hurdles he jumped through and the lengthy environmental impact statements he and his team would assemble to gain approval. “The work of art is revealed through the process of gaining permission,” he said in the March interview.

Over the years, Christo drew opposition from environmentalists who insisted that some of his projects—such as Over the River, his ultimately abandoned plan to float 42 miles of silvery fabric above the Arkansas River—would permanently damage local wildlife. Some works have also resulted in disasters: Two people died while interacting with his 1991 project The Umbrellas (a California woman died when an umbrella flew out of its base; a worker in Japan was electrocuted during de-installation).

Christo and Jeanne-Claude famously refused to work on commission, sell their public art, or accept money directly for a public project, opting instead to finance them independently through the sale of preparatory drawings, scale models, and other smaller works. (“I am an educated Marxist,” Christo told Artnet News. “I use the capitalist system to the very end. It’s economical, clever, and it’s stupid not to do it.”)

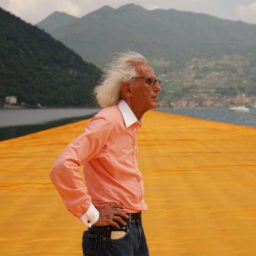

Visitors flocked to Christo’s Floating Piers (2016). Photo: MARCO BERTORELLO/AFP/Getty Images.

He was known as a fast talker, a wild gesticulator, and a stickler for specifics. (In a telling quirk, he and Jeanne-Claude’s extremely detailed website has three subsections on the “About” page: “Life and Work,” “FAQ,” and “Most Common Errors.”) But the magic of Christo’s work came when all that paperwork, engineering, and preparation would result in a finished product that the public could engage with, taking off their shoes to walk along the Floating Piers, which he erected in Italy’s Lake Iseo in 2016, or feeling the wind in their hair as they walked under the saffron curtain created by The Gates in 2005.

“All our projects are totally irrational, totally useless. Nobody needs them. The world can live without them. They exist in their time, impossible to repeat,” he said in March, repeating a common refrain he employed in interviews for years. “That is their power, because they cannot be bought, they cannot be possessed… They cannot be seen again.”