Art World

After a Van Gogh Heist Rattled Museums and Collectors, Experts Weigh in on How to Protect Your Art During a Lockdown

From break-ins to cyber attacks, here's some practical advice to secure your collection.

From break-ins to cyber attacks, here's some practical advice to secure your collection.

Naomi Rea

It was only a matter of time.

As art galleries and museums around the world began shuttering for an indefinite period in the name of public health, nefarious actors were gearing up to exploit the unprecedented situation.

One museum director’s worst fear was realized when opportunistic thieves made off with a prized Van Gogh painting from a small institution in the Netherlands. The theft was the first high-profile example of a lockdown-related art heist, and threw into stark relief the fact that collections everywhere need to brace themselves against further attempts.

Smaller institutions and empty private homes with museum-caliber collections are particularly vulnerable, but larger institutions are not infallible and should also take time to review their security measures. With limited physical staff on the ground, and preoccupied emergency services slower to react, the chances of thieves escaping with irreplaceable treasures is a real risk, even for the most sophisticated institutions.

We consulted leading security experts on their tips for how museums can guard themselves against theft during lockdown.

“I am concerned that in the rush to make their collections digitally accessible to the public during the lockdown, some museums ‘forgot to lock the door,’” Christopher Marinello, chief executive at Art Recovery International, LLC, tells Artnet News. “By this, of course, I mean take extra measures to secure the collection. CCTV and alarms do very little when law enforcement is occupied with health issues and unable to respond to the call as they would normally.”

In the first instance, Marinello advises that institutions and private collectors take time to review and update their insurance policies. “Make sure files are updated with provenance information, receipts and images,” he says. “Institutions and collectors always claim that there is never enough time for these critical exercises. Now, there is plenty of time.”

Additionally, Marinello recommends that owners review their existing security measures to ensure that all systems are functioning properly. Will the alarms go off at the right time? Are the CCTV cameras working and delivering quality footage? With law enforcement possibly slower to respond, owners could even “consider moving vulnerable collections to specialist fine art storage facilities.”

But museums need to be looking further than just battening down their own hatches. After all, the stolen Van Gogh was on loan to the Singer Laren museum from another Dutch museum. Marinello’s company represents a number of fine art insurance firms, brokers, and loss adjusters, and he says that some of these clients are now asking for the return of artworks on loan to museums or on consignment to other dealers.

The Singer Laren Museum’s general director Evert van Os speaks to the press after the theft of a Van Gogh painting. Photo by Robin Van Lonkhuijsen/ANP/AFP via Getty Images.

The physical security of museums and galleries is not the only thing at risk right now, as more galleries have rapidly transferred their day-to-day business operations to the digital marketplace. There has been an uptick in cybercrime across all industries and the often less than tech-savvy art world particularly needs to guard itself against attacks.

“Digital security measures must be put in place,” Marinello says. “While some idiot art thieves are still outside scoping out museums and galleries, others are plying their illicit trade by hacking into gallery websites, using phishing scams to gain access to invoice records, even hacking into Zoom (and other) online conference sites.”

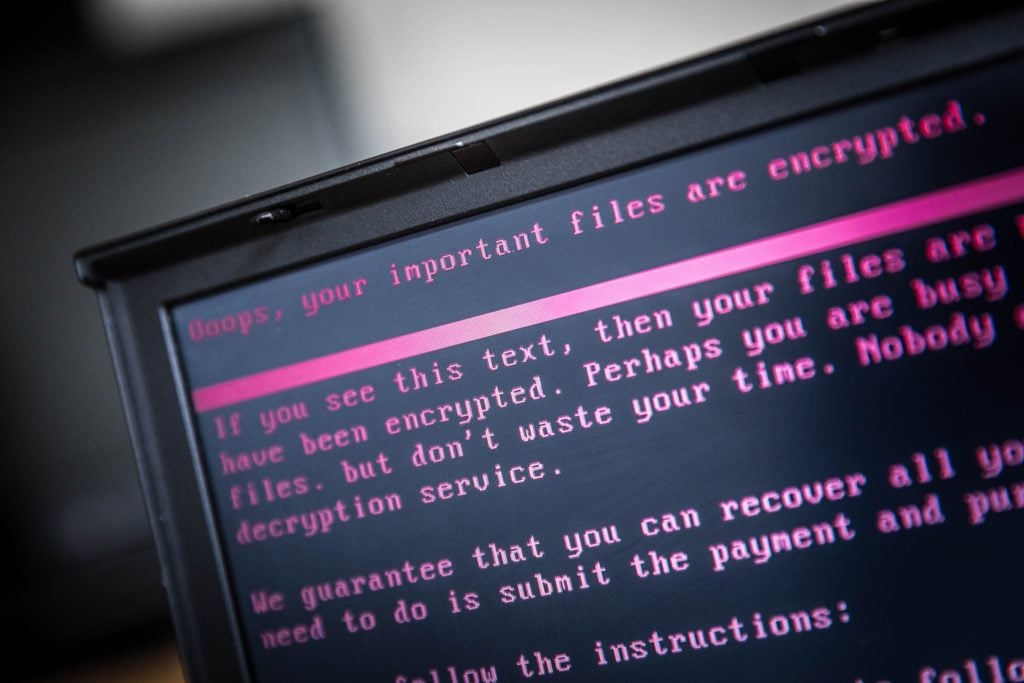

Jordan Arnold, the head of private client services and strategic risk and security at K2 Intelligence FIN, an investigations, compliance, and cyber defense service firm, also points this out. While an in-person heist is limited to what a thief can carry out, it is easier to attack at any scale online. Businesses should be wary of emails with links or attachments—some are being sent out disguised as safety guidelines and prevention tips, or even government bailout programs—that turn out to be ransomware or other cyberattacks.

Arnold warns that cyber criminals may also set up hoax donation pages for major institutions, small galleries, and even artists, to try to exploit fundraising efforts for relief for lost staff wages or declining revenue.

“The public must be extra diligent about where they are clicking and where they are entering their sensitive information, such as credit card details,” Arnold says, adding that if an institution learns of a scam that impersonates it, “they should make every effort to put out a public disclosure about the scam to inform those donors or patrons who might be inclined to contribute under false pretenses.”

A laptop displays a message after being infected by a ransomware as part of a worldwide cyberattack that hit more than 200,000 victims in more than 150 countries in 2017. Photo: AFP PHOTO/ANP/Rob Engelaar/Netherlands/Getty Images.

In terms of the physical threats collections face, Arnold emphasizes the importance of deterrents. Visible security cameras and signage indicating the presence of cameras can be powerful enough to put a criminal off, as can basic interventions such as bright lighting.

Arnold says that institutions should also consider installing temporary barriers to entry. A temporary metal barrier affixed to the structure of the building at entry points could help block illicit entry. “In the event of a theft, this kind of barrier can also slow a criminal down from exiting the building with a piece of art or artifact, allowing first responders more time to arrive on the scene,” Arnold says. Other measures include glass security film to prevent smash and grab heists such as that which happened at the Singer Laren. “Instead of the glass shattering upon impact, it will spider and make it more difficult and time consuming to break in,” Arnold says.

Finally, private collectors, galleries, and museums should all be taking regular inventory of their collections. “One of the key determinative factors in whether a theft gets solved is how much time passes between the theft and the realization that the piece is missing: the bigger that window, the less likely it is to be solved,” Arnold says.

These guidelines are good rules of thumb in any time. As special agent Chris McKeogh from the FBI’s art crime team in New York tells Artnet News, “museums are always at risk of theft carried out by those who are well prepared and determined to steal, regardless of the circumstances.”

But there might be a bright side to the lockdown. While it makes sense to take preventative measures, some experts, like McKeogh, believe that despite the incident in the Netherlands, museums could actually prove to be more secure during this period. “Most museums are closed to visitors but are still staffed by security,” McKeogh says. “A reduced number of outsiders in the museums cuts down on the risk of crimes of opportunity.”

Erin Bast, senior underwriter for the art insurance firm Huntington T. Block, agrees. “Now that it’s no longer business as usual, we’re actually seeing some risks to physical collections decrease. Museum visitors no longer pose a risk to the pieces, and transit (the top art claim) isn’t a concern because art is staying in place.” But Bast highlights another possible issue for collections, one that is not linked to theft.

“It’s important for museums and galleries to be extra vigilant when it comes to factors that can damage art like shifts in temperature or humidity in rooms storing art, pests, and open doors and windows,” Bast says. When museums are vacated in a hurry, common sense conservation practices might fall to the wayside. She suggests that it would be worthwhile to have someone on the ground monitoring temperature and humidity.

Situations like we’re in now “provide learning opportunities and new chances to improve future plans,” Bast says. “If you aren’t sure what to do, reach out to others around you and don’t be afraid to ask questions.”