Art World

Strange Cones Depicted on the Heads of Ancient Egyptians Puzzled Scholars for Years. Now the Mystery Has Been Solved: They Were Hats

Still, Egyptologists basically have no clue what the actual purpose of this enigmatic headgear was.

Still, Egyptologists basically have no clue what the actual purpose of this enigmatic headgear was.

Karen Chernick

We dare you to spot an ancient Egyptian who isn’t sporting some kind of headgear. From fishermen to pharaohs, ancient Egyptians were forever wearing wigs, crowns, and headbands associated with specific roles and rituals, and archaeologists now know many of these accessories by name. The blue Khepresh crown, for example, was worn by pharaohs going into battle and the Nemes headdress—that striped linen headcloth with two flaps hanging down over the shoulders—was reserved for royalty.

One headpiece depicted in sculptures and paintings has puzzled Egyptologists, though, and that is a small, cone-shaped cap, most often white, at other times bedazzled. The cones appear atop the heads of ancient Egyptians in visual representations spanning a stretch of nearly 1500 years from the early New Kingdom to the Ptolemaic period. They’re usually worn by banquet guests, people being rewarded by a king, or folks doing everyday things in the afterlife. Alternatively, the caps may be associated with childbirth and fertility.

Book of the Dead of Hunefer (19th Dynasty), papyrus. Image via Wikimedia Commons

“The nature and role of the cones have long been debated,” writes a team of archaeologists in a new study published this month in Antiquity journal. “In the absence of any convincing examples of head cones from archaeological contexts, scholars have questioned whether the cones were ever produced as three-dimensional objects, or were instead entirely symbolic of anointing or beautification rituals or of more abstract ideas.”

But now, after a recent discovery in the ancient city of Akhetaten (also known as Amarna), archaeologists know that these cones were very real. Cemetery excavations conducted since 2005 as part of the Amarna Project (on behalf of the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research at the University of Cambridge) have extracted 700 graves—and two beeswax cones.

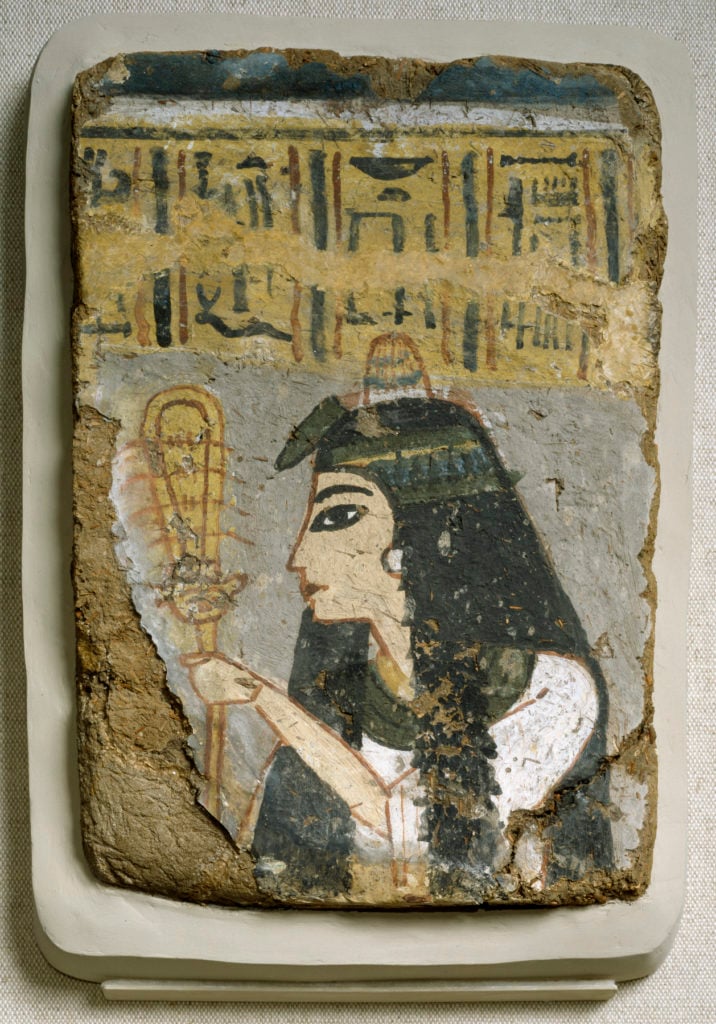

Wall Painting: Woman Holding a Sistrum (ca. 1250-1200 BC), The Walters Art Museum

One of these cones was found on top of the skull of a 29-year-old woman, with her hair still coiled inside. The other was found with the grave-robbed remains of a teenager, gender unknown. The burials of these two cone-wearers were simple in style, not reflecting upper-class origins.

The mysterious cones were not symbolic illusions, then, but actual hats. Research is ongoing, but the discovery will help Egyptologists learn the meaning and function of these domes, which until now were believed to have existed only in paintings and sculptures.