Art & Exhibitions

What Should We Do With Fallen Confederate Statues? An L.A. Show Asks—and Answers

Including a new commission from Kara Walker, the show includes decommissioned monuments and contemporary artists’ responses.

Including a new commission from Kara Walker, the show includes decommissioned monuments and contemporary artists’ responses.

Brian Boucher

America continues to contend with its past, often in the messiest ways imaginable. Just this weekend, millions marched in No Kings demonstrations around the country, protesting president Donald Trump’s authoritarian overreach; the White House reliably (and embarrassingly) trolled the protesters with a photo of Trump and vice president J.D. Vance wearing crowns, as if forgetting the very reason the Revolutionary War was fought. A few years ago, at the height of the Black Lives Matter movement especially, monuments to Confederate officials were graffitied and torn down in cities across the country in protest of the racist worldview they embodied.

Now, “MONUMENTS,” a long-awaited show that hopes to find something generative in looking at those felled monuments to the “Lost Cause,” opens at two institutions in Los Angeles.

Ten decommissioned monuments come together with existing and commissioned works by 19 contemporary artists in the show, which is a collaboration between the Brick (formerly LAXART), headed up by Hamza Walker, and the L.A. Museum of Contemporary Art, whose participation is helmed by senior curator Bennett Simpson. Nominally a co-organizer, though she wasn’t involved in choosing works, is New York artist Kara Walker (no relation to Hamza); the show includes a dramatic commission by her. “MONUMENTS” has been in the works since 2017, and came to public attention in 2021, when Walker revealed his plans on the Hope and Dread podcast, hosted by art advisor Allan Schwartzman and journalist Charlotte Burns.

Installation view of “MONUMENTS” at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA and the Brick, Los Angeles. Laura Gardin Fraser, Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson (1948), and Hank Willis Thomas, A Suspension of Hostilities (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery. Photo: Stefanie Keenan/Getty Images for The Museum of Contemporary Art.

The historical artifacts on view include two whose centrality to bloody recent history can hardly be exaggerated: monuments to Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson that were at the center of the “Unite the Right” neo-Nazi and white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017. After white supremacist James Alex Fields Jr. drove his car into a crowd of counter-protesters, killing Heather Heyer, Trump would memorably say that there were “very fine people on both sides.” The Brick had been granted ownership of the Jackson monument by a unanimous vote of the Charlottesville city council; it is one of nearly 200 Confederate monuments that have been destroyed or decommissioned.

The oldest artifact in the show is also a whopper: a statue of Supreme Court Justice Roger B. Taney, who wrote the 1857 Dred Scott decision, which included the words: “There are no rights that a black person has that a white man is bound to respect.” Unveiled in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1887, it was removed from public view by the city in 2017, amid the nationwide wave of protests associated with the Black Lives Matter movement.

Alongside the monuments are newly commissioned works by Walker along with artists including Karon Davis, Abigail DeVille, Stan Douglas, Kahlil Robert Irving, and Cauleen Smith. Some pieces respond directly to the decommissioned monuments, while others offer contemporary commentary on the historical themes the monuments put in play. What’s more, there will be loaned works by contemporary artists including Nona Faustine, Martin Puryear, and Hank Willis Thomas.

Nona Faustine, Ye Are My Witness, Brooklyn, NY (2018). Courtesy of the Estate of Nona Faustine and Higher Pictures.

The show promises visual fireworks and pointed combinations of historical and contemporary. There will be bronze ingots from Charlottesville’s melted-down Robert E. Lee statute, the New York Times revealed. Filmmaker Julie Dash created a piece, HOMEGOING (2025), featuring opera singer Davóne Tines and set in Charleston’s Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, where nine parishioners fell to a white supremacist’s attack in 2015. A statue of Jefferson Davis, the only president of the Confederacy, was pulled down from its pedestal in Richmond and bombed with paint, Simpson explained on a video call; this “really interesting-looking artifact” will be surrounded by Andres Serrano’s portraits of leading figures in the Georgia Ku Klux Klan.

But the star of the show is Kara Walker, the sole artist whose work will appear at the Brick. Just as a Hollywood filmmaker might need to attach a big name to a project to get it off the ground, Hamza Walker told me in 2021, he figured from the outset that he would need to recruit a high-profile co-conspirator. Talking to the Times recently, he said, “To me, Kara’s piece is the whole thing. The show could almost be considered an excuse to get one of those things into Kara’s hands.”

Kara Walker, Unmanned Drone (2023). Photo: Ruben Diaz. Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Malloy Jenkins.

Her piece, which represents the dismantled and rearranged Jackson monument—literally beheaded in the process—is titled Unmanned Drone (2003). Titling the piece for a weapon of war highlights the role of Confederate monuments, which were erected long after the Civil War in what might be termed a racist propaganda war. The 1921 monument, by New York sculptor Charles Keck, shows Jackson on his horse, Little Sorrel, which itself became massively popular after the Civil War, and became an object of some fascination for the artist. The end result presents a frightening 11-foot-high hybrid of Jackson and his steed.

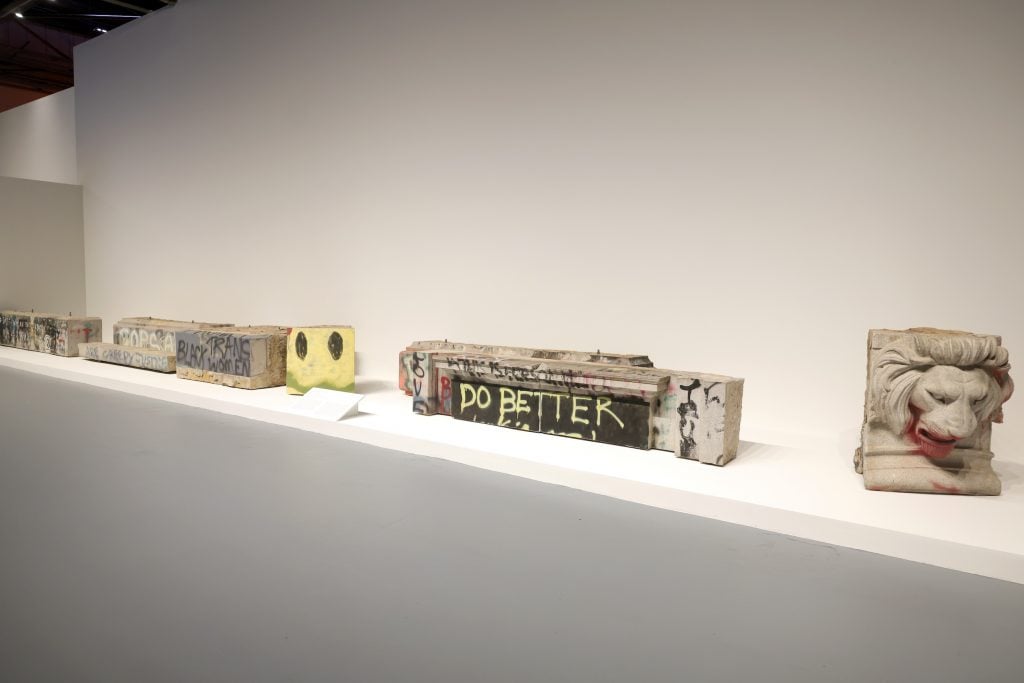

“The first thing you’ll see in the Geffen are the chunks of granite from the base of the Robert E. Lee statue in Richmond,” said Hamza Walker in the video call, adding that the chunks of stone are heavily graffitied. “That is the calling card for the show: the dismantling with visible signs of protest on the chunks of granite. The stone has an archaeological feel, almost, combined with the urgency of the spray paint.”

Installation view, “MONUMENTS,” at the Brick and the Geffen Contemporary at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art. Photo: Stefanie Keenan/Getty Images for the Museum of Contemporary Art.

One of the centerpiece juxtapositions, Simpson explained, is between a monument to Matthew Fontaine Maury, a Confederate naval commander and oceanographer, and paintings created in response by Walter Price. “They’re abstract paintings—Hamza called them the progeny of Bruce Nauman and Alma Thomas—made with his feet, marching back and forth across the canvas. They have a panoramic, underwater feeling. Walter wanted to deal with Maury because he had been in the Navy, so he has a personal affinity to that context.”

“MONUMENTS” at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA and the Brick, Los Angeles. Frederick William Sievers, Matthew Fontaine Maury Globe (1929), center, with paintings by Walter Price. Photo: Stefanie Keenan/Getty Images for The Museum of Contemporary Art.

Red tape is a part of any artwork loan. First of all, the curators had to convince the lenders that they would treat these objects with the same level of care they would any work of art. But in the case of the monuments, there was sometimes ambiguity regarding who actually had the authority to greenlight a loan request.

In some cases, the local authorities understood very well the “Lost Cause” ideology that underpinned these statues—”one of the greatest propaganda campaigns ever waged in this country,” said Walker—and were keen to agree to the loan. But the chain of command wasn’t always clear. In Baltimore, though the city claimed ownership of the object, the Maryland Historical Trust has the easement of the property where it was sited. In other places, like Boston and Pittsburgh, the local department of cultural affairs owned the object and made the decision.

“Things were unfolding in real time,” said Simpson. “The monuments had just come down in the past year or two. It really was not clear what the future of the objects would be.” Added Walker, “It still isn’t!”

Elsewhere, the extremely sensitive nature of these particular artifacts added a more emotional dimension to what might usually be just a bureaucratic process. Sometimes, said Walker, the reaction was, “Why do you want to do this? You’re not making fun of us, are you?” But, he said, “Museums are not in the business of making fun of people.”

The heady days of the wholesale removal of Confederate monuments may be in the past, and in fact there has been a concerted backlash to that iconoclastic moment, Walker pointed out.

“MONUMENTS” at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA and the Brick, Los Angeles. Right: Edward V. Valentine, Jefferson Davis (1907). Left: Andres Serrano’s portraits of members of the Georgia Ku Klux Klan. Photo: Stefanie Keenan/Getty Images for The Museum of Contemporary Art.

“I would make an argument that ideologically the South is rising again,” he said, reeling off a list of moves by public and private entities to rehabilitate the same people whose monuments were torn down. The National Park Service announced in August that it would replace a monument to Confederate army officer Albert Pike that was taken down from its perch in Washington, D.C. in 2020. The mealy-mouthed press release claims that it will honor his leadership in Freemasonry; there is no mention of his military role.

An Alabama town recently installed a new monument to Confederate admiral Raphael Semmes after the original was vandalized and removed in 2020. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, meanwhile, undertook to return all the names of Confederate generals to U.S. Army bases—defying a 2021 law barring the use of their names by finding soldiers with the same surnames and saying (again, mealy-mouthed) that the bases are now devoted to them.

And, on the private side, at a park in North Carolina, an individual has opened Valor Memorial, a private park “dedicated to resurrecting Confederate statues that municipalities removed from public view,” as the Times reported just this month.

Walker likened these initiatives to trolling and dog whistles.

“This is the kind of episode,” he said, “that we read about in history books and go, ‘They did what?’”

“Monuments” will be on view at the Brick, 518 North Western Ave, Los Angeles, and the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, 250 South Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, from October 23, 2025–May 3, 2026.