The Expressionist artist Cornelia Gurlitt (1890–1919) is hardly known outside of Germany, and there, too, only specialists and art historians interested in the era around World War I, when she was most productive, are familiar with her work.

For the rest of the world, her name will ring a bell for very different reasons.

Cornelia was the aunt of Cornelius Gurlitt (1932–2014), who was famously caught, back in 2012, with a trove of art hidden in his Munich and Salzburg homes. Stashed away for decades, the 1,500-strong collection was mostly amassed by Cornelius’s father Hildebrand—Cornelia’s younger brother—who for several years in his long career as an art dealer also worked for the Nazis.

The sensational discovery brought to light many works believed to be lost forever; so far, six pieces have been identified as Nazi-loot and restituted, and provenance research is ongoing. But the find also revealed the work of Cornelia Gurlitt, which, in a twist of fate, nearly sank into oblivion because of her brother’s secrecy about his collection after World War II.

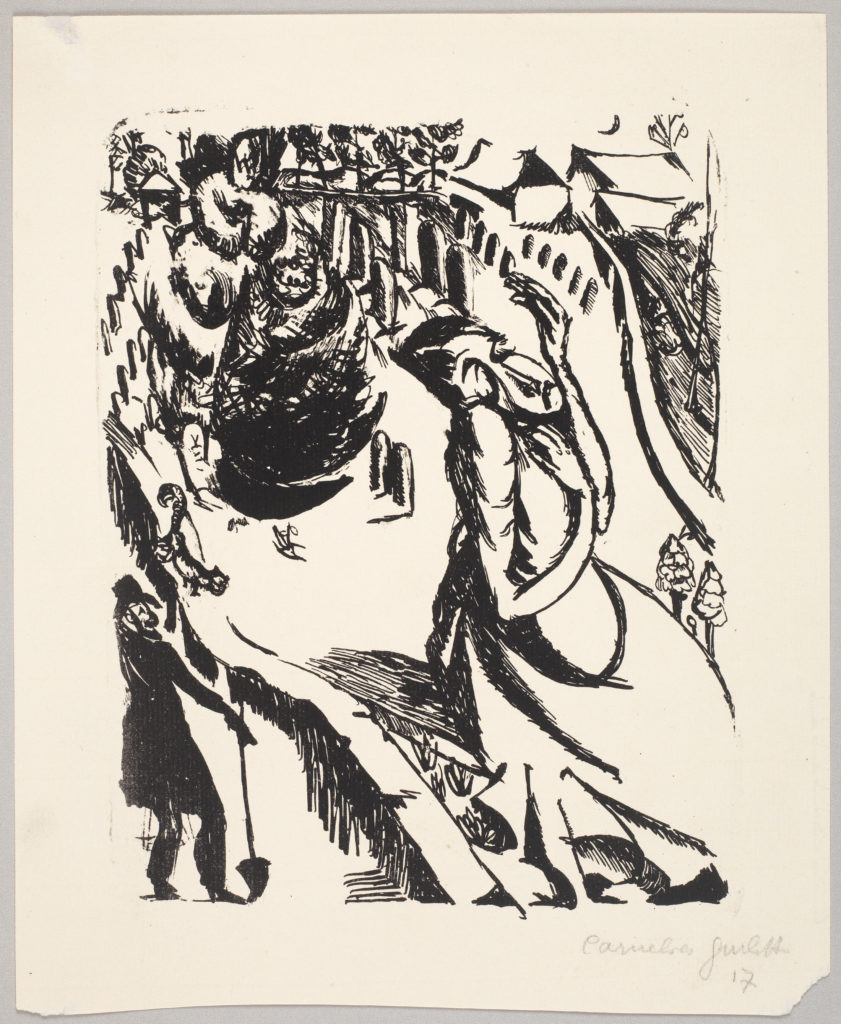

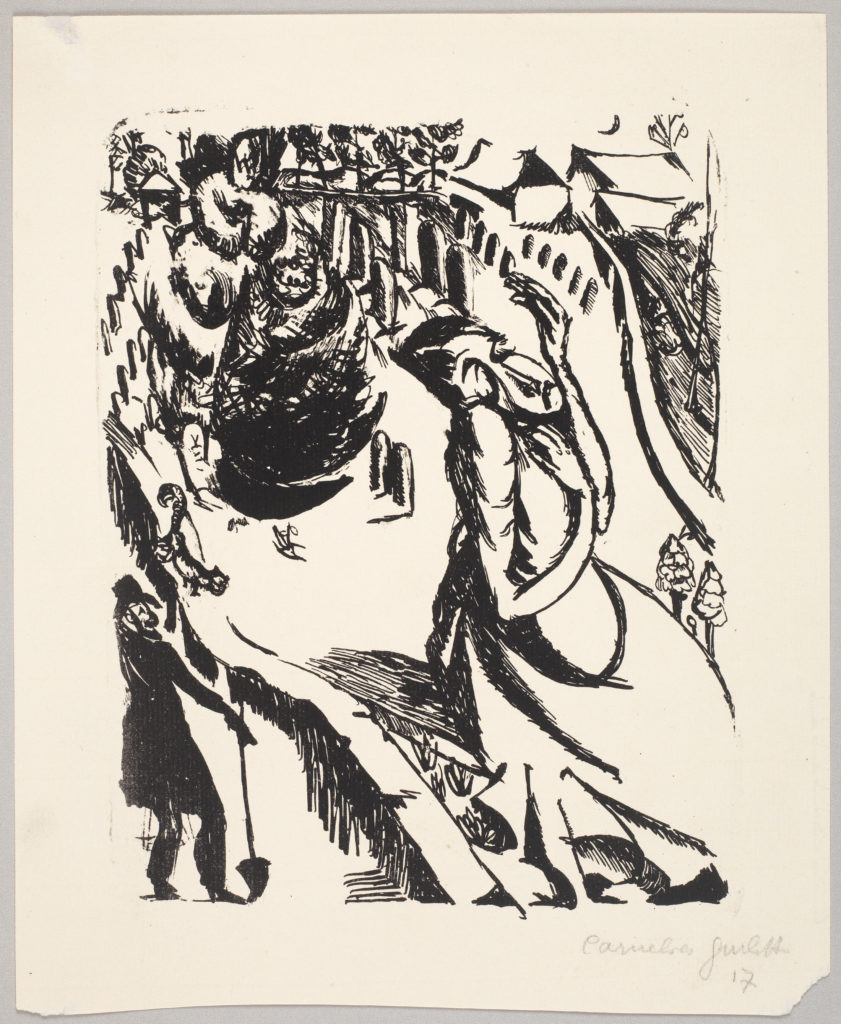

Cornelia Gurlitt, Friedhof, (Cemetery) (1917). Kunstmuseum Bern, Bequest of Cornelius Gurlitt, 2014.

Earlier this month, two concurrent exhibitions in Bern in Switzerland, and Bonn in Germany finally made about a third of the clandestine art hoard accessible to the public, and many works by Cornelia Gurlitt went on view for the first time.

“Her drawings, lithographs, and paintings of the time were among the most powerfully expressive works of those years,” wrote the German art critic Paul Fechter in 1949, noting that German Expressionist groups, including Brücke or Der blaue Reiter, were predominantly male.

“This woman, whose name and achievement is known only to a small circle of people, was perhaps one of the greatest talents of the younger Expressionist generation,” Fechter wrote of the young artist, who was also his lover, during World War I.

Cornelia Gurlitt, Courtesy TU Dresden Archive.

During the war, Cornelia Gurlitt was a field nurse on the Eastern Front in Vilnius, Lithuania. Those years marked an intense and transformative period in her artistic production. There, she captured the multicultural atmosphere of the city, thereby producing some of the few, rare depictions of everyday life in the city’s Jewish quarter.

“Under the influence of Marc Chagall, Cornelia Gurlitt set down a highly personal vision of Jewish life in the Lithuanian capital, a world that most Germans would not have been familiar with,” notes the catalogue text accompanying the two exhibitions of the Gurlitt collection.

Shortly after returning from the Eastern Front, Cornelia moved to Berlin hoping to make a living as an artist. Suffering from depression, she committed suicide in 1919, at the age of 29.

Before her death, Cornelia appointed her brother, Hildebrand, as her executor. With many of her works out of view in his art collection, her name fell into near obscurity—until the discovery of her nephew’s tainted inheritance made sensational headlines. In 2014, Hubert Portz, a German psychotherapist and amateur art historian who has been hunting for work by Cornelia Gurlitt for years, contacted the reclusive Cornelius as he suspected her work could be in the trove, but received no reply.

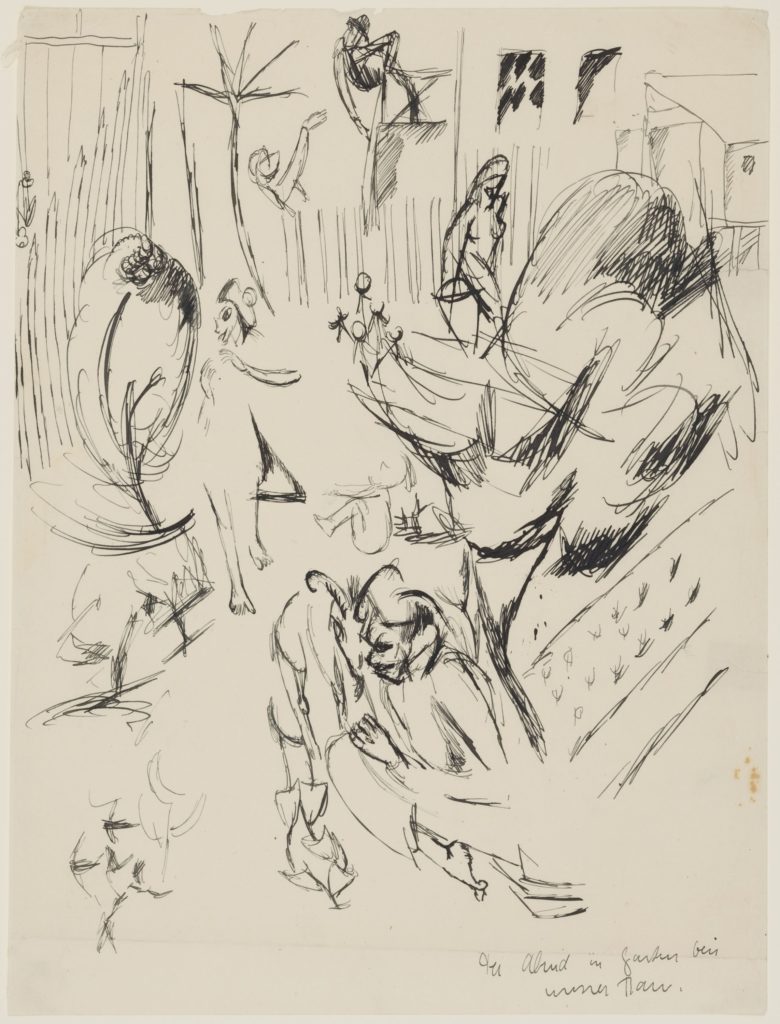

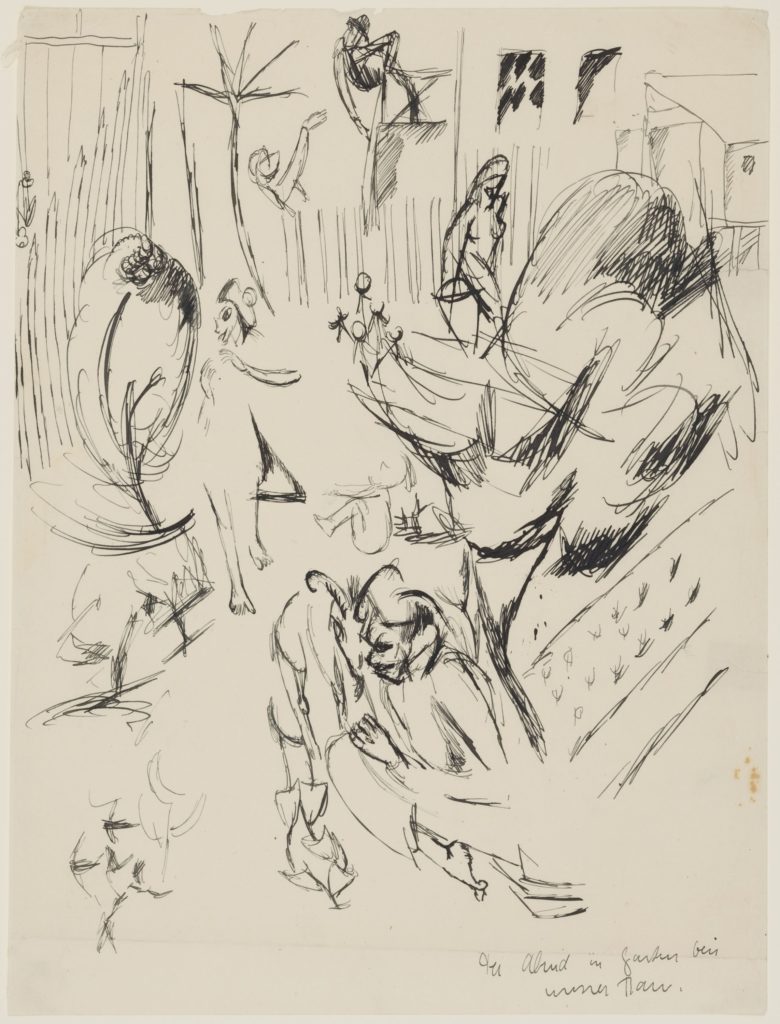

Cornelia Gurlitt, Personen im Garten, Kunstmuseum Bern, Bequest of Cornelius Gurlitt, 2014.

Cornelia’s most dedicated collector, Protz staged an exhibition that year including much of her known work at the Kunsthaus Desiree, Hochstadt, a former branch of the Sparkasse bank that he had converted into a museum. The show featured 23 pieces by Cornelia: nine were acquired from Frankfurt’s Galerie Joseph Fach, and had previously belonged to the descendants of Cornelia Gurlitt’s former lover, Paul Fechter. An additional 11 lithographs Cornelia had given to a friend before her death turned up in response to a newspaper advertisement. Some of the other works, which include an oil painting of Hildebrand, were lent to the exhibition by members of the Gurlitt family—but not Cornelius.

In addition to these, some of Cornelia’s most haunting work are in the collection of the Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum in Vilnius. Earlier this year, both Protz and the Lithuanian museum lent works by Cornelia Gurlitt to documenta 14, where 17 works on paper and one of her lithographs were on view at the Neue Galerie in Kassel.

With more of her output soon available for scholarly research—once the provenance of the works in Hildebrand’s collection is cleared—this forgotten figure of German Expressionism might finally get her due.