Satellite imagery from the Corona project, a Cold War spy program that acquired military intelligence about the Soviet Union for the US, is proving useful in ways its creators could have never imagined—including for archaeologists.

“Corona is like a time machine for us,” Jason Ur, a Harvard University archaeologist who works with Corona images, told the New York Times. “In a lot of cases, they lead us to landscapes that are gone, that don’t exist anymore.”

A trove of some 850,000 images were taken by Corona satellites between 1960 and 1972, after President Dwight Eisenhower approved it as part of the world’s first space imaging program. A spy satellite offered an unprecedented view of the enemy and its missile sites, warships, and military bases.

Today, those high-resolution images represent a snapshot of an earlier planet, making visible global ecosystem transformations that happened right under our noses, including from the effects climate change. Spanning nearly the entire globe, the photographs were declassified in the mid-1990s.

Examples of recent land use changes detectable on CORONA imagery: A) Western Mexico City, where massive urban sprawl has destroyed archaeological remains; B) Indus River Valley, Pakistan, where intensified irrigation agriculture has obscured archaeological sites; C) Three Gorges Dam, China, where construction of the world’s largest dam project has submerged countless archaeological sites. CORONA imagery courtesy US Geological Survey; Modern satellite imagery ©ESRI and DigitalGlobe.

Archaeologists are particularly interested in what Corona images reveal about areas of the near and Middle East that have undergone rapid development in recent decades, destroying archaeological sites and ancient roads and irrigation systems.

Corona has been an invaluable tool for Ur in what he calls remote sensing, using aerial photographs and satellite imagery to view the landscape from above, and identify lingering evidence of features from the ancient world.

Analyzing Corona imagery, Ur has spotted “communication networks of the Early Bronze Age, state-sponsored irrigation under the Assyrian and Sasanian empires, and pastoral nomadic landscapes in northwestern Iran and southeastern Turkey,” he writes on his website. These large-scale features, if still in existence today, would be all but invisible on the ground, without the aid of the full picture.

Ur’s findings even inspired an exhibition, “Spying on the Past: Declassified Satellite Images and Archaeology,” at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in 2011.

CORONA imagery courtesy US Geological Survey; Modern satellite imagery ©ESRI and DigitalGlobe.

To date, only about five percent of the images have been scanned (and each photograph costs $30 to digitize). Because the perspective of the satellite distorts spacial accuracy of the terrain, images require orthorectification before geographic features can be seen in their true position. But the software used to correct the images has improved in recent years.

At the University of Arkansas, the Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies has compiled a publicly available image database of 2,214 Corona photographs that identify 803 archaeological sites. Researchers there have developed Sunspot, a free open-access system for mapping Corona imagery to terrain as captured in modern Google Earth imagery.

Corona’s 20th-century images are a valuable supplement to today’s satellite shots, drone photography, and imaging technology, such such as LiDAR, a once prohibitively expensive means of gathering topographic data that is now being increasingly funded by government agencies, yielding an unimaginable wealth of archaeological discoveries.

Over 2,000 years after its construction, a 100-meter-wide canal near Bandwai is clearly visible in the satellite image. Photo by USGS/Jason Ur, 1969.

Corona imagery has also been used by Romanian forest engineers studying landscape history, biologists tracing the destruction of Chinese mangroves, geoscientists forecasting water levels in a Nepalese lake, scientists measuring rock glacier movements in central Asia, and biogeographers tracking marmots’ nesting habits amid destructive agriculture practice in Kazakhstan.

“We can use imagery in the past to inform the future,” University of Leeds geoscientist C. Scott Watson, told the Times.

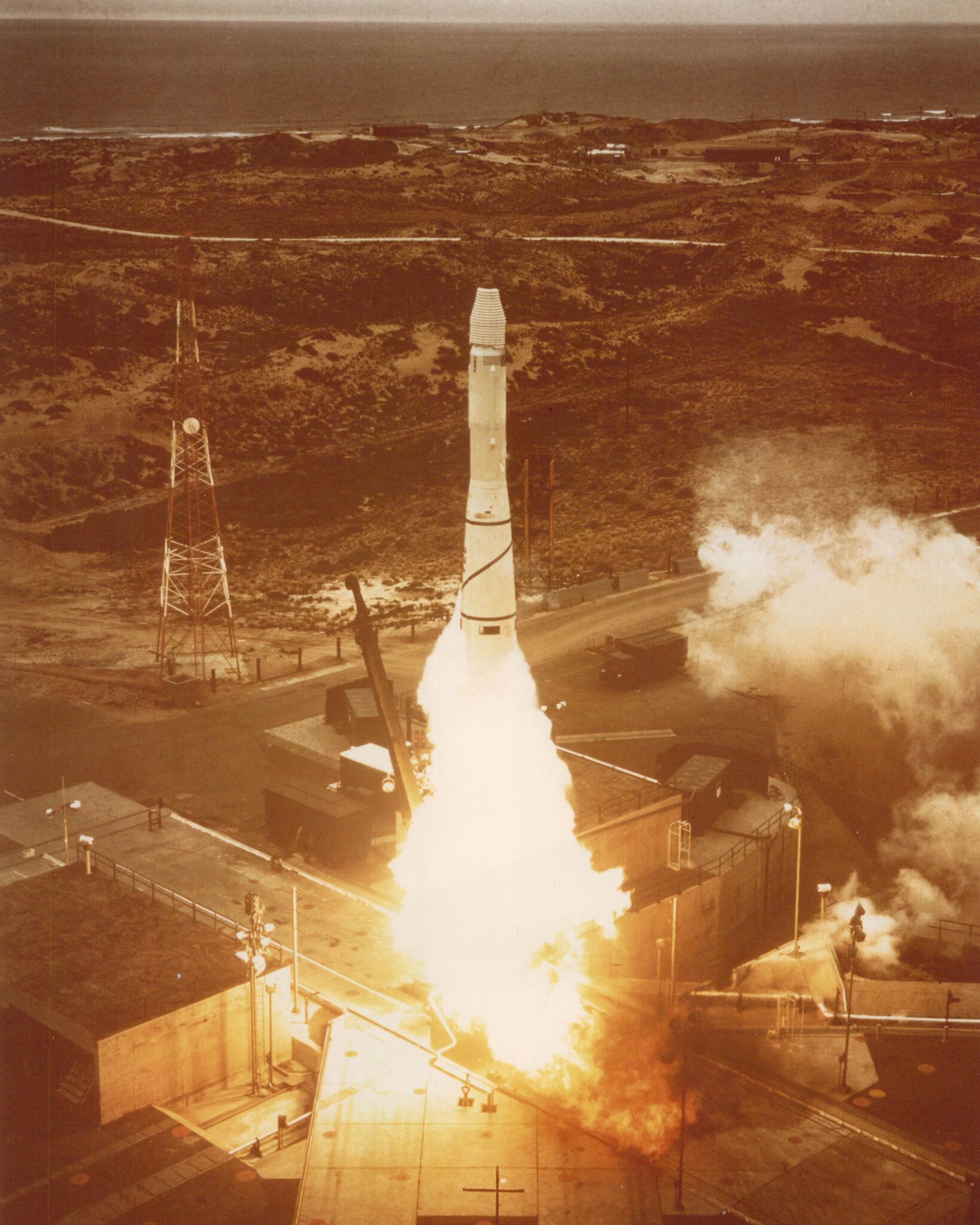

At the time of its creation, Corona also represented an impressive feat of engineering, requiring the development of film that could survive space radiation and high air pressure—not to mention be retrieved from a satellite orbited high above the atmosphere. After a dozen failed launches, the first successful Corona flight managed to make eight passes over the USSR. An Air Force plane retrieved the 20 pounds of film in midair as it floated down to Earth by parachute.

The program was phased out after the invention of satellites that could beam imagery back to Earth digitally, following 145 missions (120 of which successfully delivered their photographs). And while many photographs are unusable due to cloud cover, atmospheric conditions, or other technical difficulties, much remains to be learned from Corona’s historic archive.