A resourceful archaeologist has made the stunning discovery of 27 new ancient Maya sites—all without ever leaving his desk.

Takeshi Inomata, an researcher at the University of Arizona, made his discoveries using freely accessible light detection and ranging maps (LiDAR for short) published in 2011 by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography in Mexico, according to the New York Times.

The organization created the map, which surveys 4,400 square miles of land in the Mexican states of Tabasco and Chiapas, with an eye toward serving businesses and researchers. An even though the imagery is low resolution, it still suited Inomata’s needs, especially considering it was free. (Inomata recently spent $62,000 on a less fruitful LiDAR map, and even then the price reflected a steep discount.)

Using the technology, Inomata—who specializes in the origins of Maya civilization and its links to the early Olmec people—identified ceremonial sites never before seen by scholars.

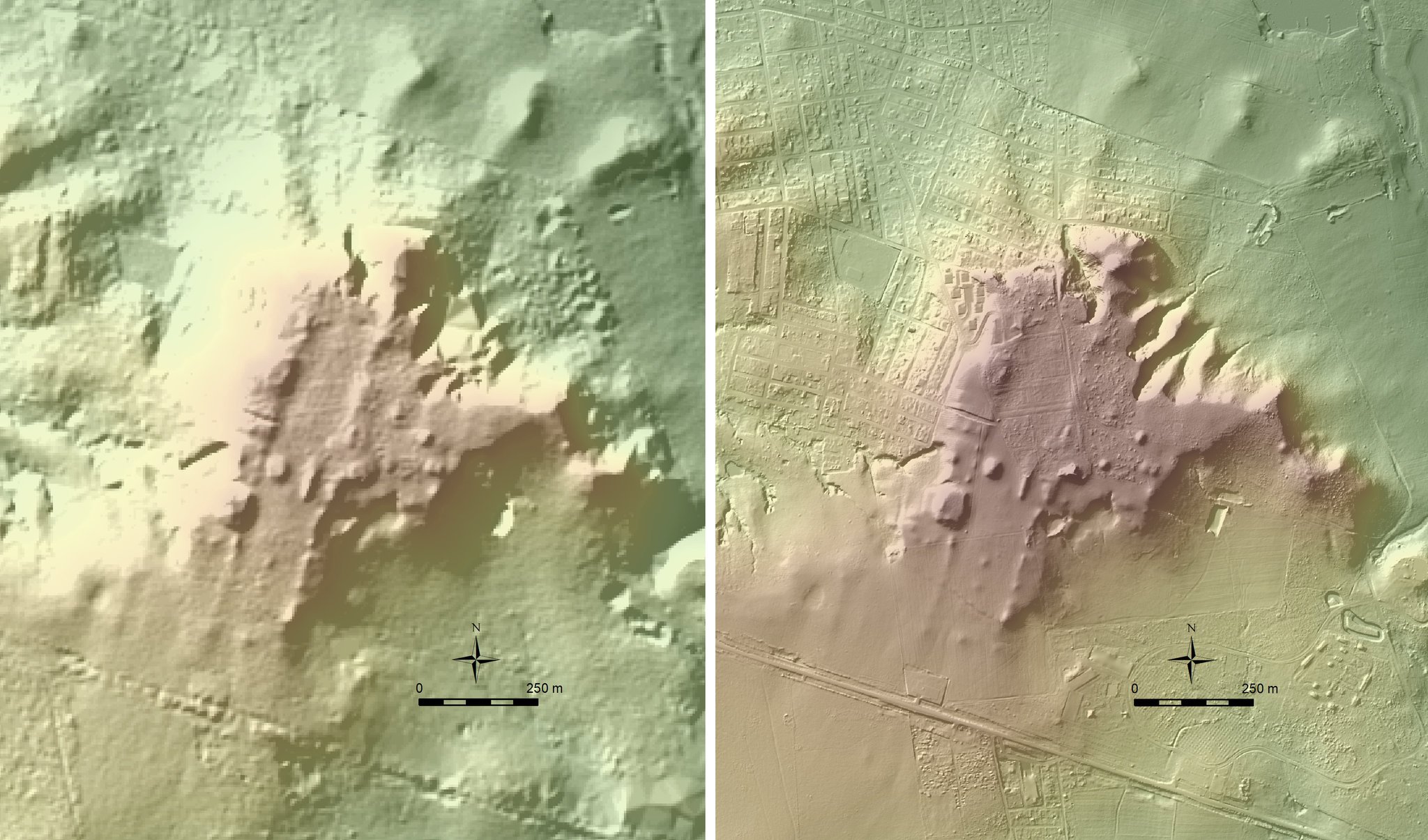

Takeshi Inomata identified this ancient Maya site, dubbed La Carmelita, using LiDAR. But the structures are difficult to see with the naked eye. Photo by Takeshi Inomata.

Inomata’s new findings include large constructions that are low to the ground, up to two-thirds of a mile in length, and easily obscured by thick brush.

“If you walk on it, you don’t realize it,” Inomata told the Times. “It’s so big it just looks like a part of the natural landscape.”

His findings are now inspiring other archaeologists to take a look at publicly available LiDAR maps.

Using NASA data from a survey of Mexico, Charles Golden, an anthropology professor at Brandeis University, spotted ancient settlements near the Usumacinta River on the Mexico-Guatemala border. And more maps will be available soon, with countries including the US launching LiDAR initiatives.

“The future pattern,” Inomata said, “will be that everything will be covered by LiDAR, like topographic maps today.”

The potential applications of LiDAR, which has revolutionized Maya archaeology, have been known since 2009, but archaeologists in Guatemala shocked the scholarly world in 2018 when they used it to discover thousands of Maya ruins.