Art World

What Our Data Dive Reveals About Artists at This Year’s Venice Biennale

This year's event has more artists than ever. How do they stack up to those included in previous editions?

There is no greater international showcase for contemporary art than the Venice Biennale. It can immediately accelerate an artist’s career by landing them in the eyeline of world-class curators and mega-galleries. Whoever is appointed to curate each edition of the Biennale wields serious power, selecting for their main exhibition the artists that they wish to bring to the art world’s attention.

The curator of this year’s 60th edition, Adriano Pedrosa, hails from Brazil and is currently artistic director of the São Paulo Museum of Art. He is the first Latin American curator and the first to openly identify as queer. His chosen theme, “Foreigners Everywhere,” takes the term “foreigner”—or its equivalent straniero in Italian, meaning “stranger,” to refer broadly to all manner of marginalizations from mainstream society.

Speaking on Artnet’s The Art Angle podcast, Pedrosa described feeling a sense of “huge responsibility” to curate the show “strategically.” He introduced a nucleo storico, or historical nucleus, specifically to give belated recognition to overlooked artists who worked for decades at the very fringes of the male-dominated, Western art world.

“What I’m trying to do is almost a speculative exercise,” he added. “It’s a draft, it’s an essay, it’s a provocation.”

It only requires a quick scan of Pedrosa’s artist list to notice marked differences with those of previous editions. For one thing, the main exhibition will be the biennale’s largest ever, with 331 artists announced. That’s many more names to remember compared than to 2022’s event, when Cecilia Alemani picked 213 artists, let alone the mere 83 chosen by Ralph Rugoff in 2019.

We took a closer look at the artists on this year’s list, as well as the lists from previous editions, charting where they born and when to get a better picture of how wide-ranging and diverse the 2024 biennial truly is.

A global scope

Unsurprisingly, there is a much bigger presence of artists from the Global South. Some countries, like Bolivia, Guatemala, Tajikstan, and Cameroon, are relative newcomers to this historically Western-centric event, having been absent from the main exhibitions of 2022 and 2019. In order to better understand this trend, Artnet News has compared the geographical spread of artists included in the main exhibition for the three most recent editions between 2019 and 2024.

Artist collectives have been removed from the data, as have the some 40 artists exhibiting as part of curator Marco Scotini’s Disobedience Archive at this year’s 60th edition, since the information about these participants provided by the biennale is incomplete. All artists have been categorized according to the global region in which they were born. Worth noting, however, is that plenty of the artists will have emigrated and may now identify with a different nationality than that of their birth country. For example, one section of “Foreigners Everywhere” is explicitly focused on 40 artists who are first or second-generation members of Italy’s large Diaspora.

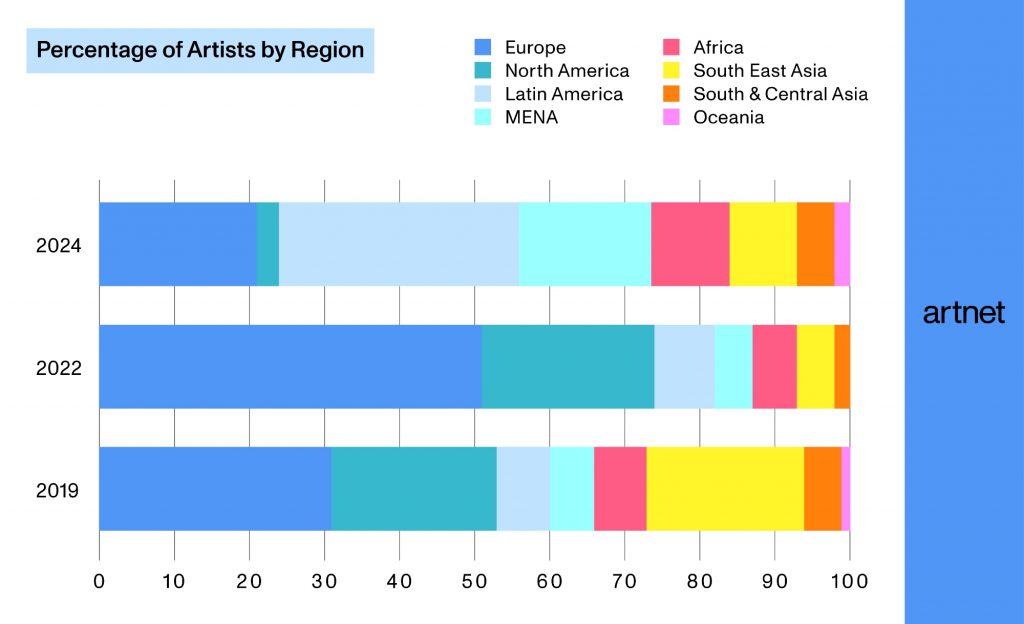

A chart showing how the geographical spread of artists in the main exhibition has changed over the three most recent editions of the Venice Biennale. Image: Artnet.

Looking at the numbers, a stark increase in the proportion of non-Western artists is immediately evident. In 2019, just over half of the artists chosen by New York-born, London-based curator Rugoff were born in Europe or North America. With 16 artists, the U.S. was easily the most represented country.

In 2022, about half of the artists picked by New York-based Italian curator Alemani were European and almost 75 percent were born in the West. Though her lineup was one of the biennale’s most nationally diverse, boasting artists from 58 countries, her predominant focus was on improving the representation of women and gender non-conforming artists to “challenge the figure of men as the center of the universe.”

The number of Western artists has shrunk to around a quarter of the total cohort at this year’s main exhibition. Instead, about one third of the artists were born in Latin America, which includes Pedrosa’s native Brazil. The percentage of artists born in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has also risen substantially from 5 percent in 2022 to 17 percent in 2024.

In keeping with this trend, the percentage of artists born in Africa, South East Asia, and South and Central Asia have all roughly doubled. Still, artists from these regions remain distinctly in the minority.

“Some of these [artists] are canonical figures in their own contexts that were really not well known internationally,” said Pedrosa. “They didn’t have the chance to participate in the Biennale. So in a way, it’s almost as if the Biennale is paying a debt towards these artists.”

Historical additions rise

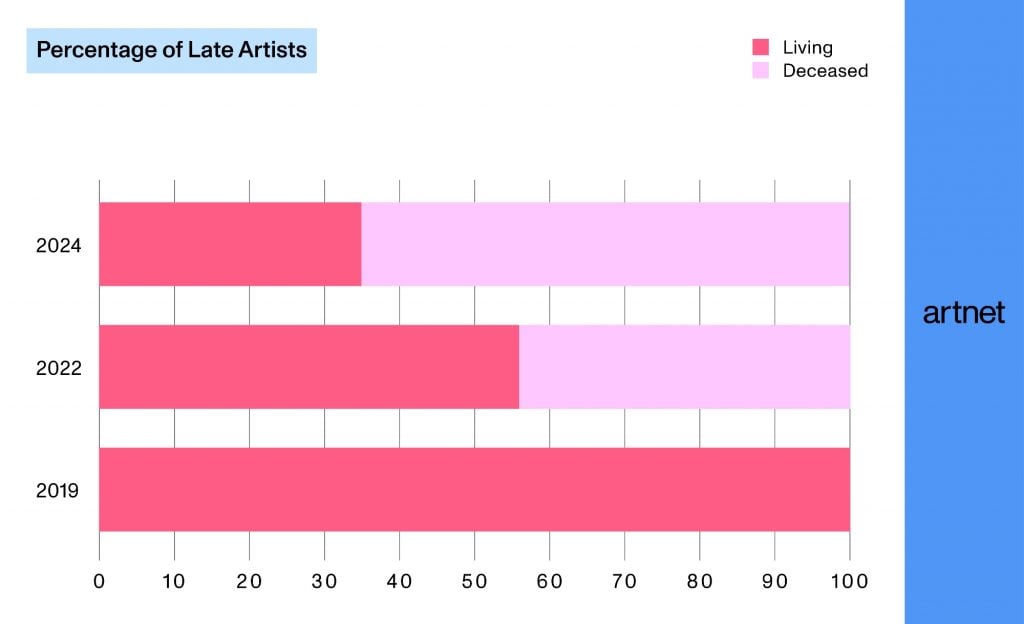

Like Alemani before him, Pedrosa is putting the spotlight on historical artists who may have been overlooked within their own time. In 2022, critics remarked on a sharp rise in the number of deceased artists included in the show. These late greats made up nearly half the total cohort, but surprised onlookers then could not have predicted that this figure would rise to two-thirds in 2024. Nearly 50 of these deceased artists were born in the 19th century.

Again, these figures do not include artist collectives or those artists associated with the Disobedience Archive, who are mostly still living.

A chart showing how the ratio of living to deceased artists in the main exhibition has changed over the three most recent editions of the Venice Biennale. Image: Artnet.

“It’s a very exciting time in art history because many of us in different parts of the world are discovering artists within the 20th century,” said Pedrosa. “My approach is these artists are not well known internationally, so I believe their work has a contemporary relevance, in that sense.”

He also noted that most artists in the historical nucleus are usually only represented by one work while those in the contemporary nucleus each have more space.

Older artists get their due

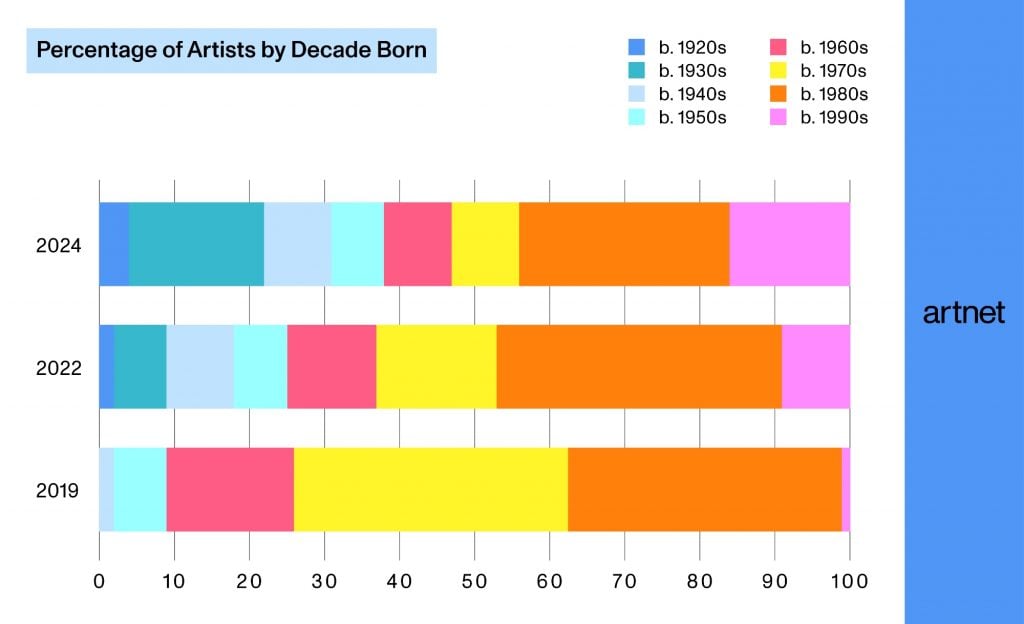

Among the living artists included in this year’s edition, there is also a higher representation of older artists. Whereas in 2019, those born after 1970 accounted for about 70 percent of main exhibition’s living artists, their presence has shrunk by about 10 percent each year. In 2024, they account for just over half of the living artists on show.

A chart showing how the typical age of living artists in the main exhibition has changed over the three most recent editions of the Venice Biennale. Image: Artnet.

In 2019, none of the main exhibition’s were born before 1940, whereas about 10 percent were in 2022. In 2024, this figure more than doubled to just over 20 percent. Overall, artists who were born before 1950, or in other words, artists who are currently at least 74 or older, make up about a third of the living artists included in “Foreigners Everywhere.” Meanwhile, the proportion of artists born in the 1950s has held steady. Artists born in the 1960s and 1970s made up about half the main exhibition’s living artists in 2019, and represent just under 20 percent now. Those born in the 1980s and 1990s represent roughly 44 percent.

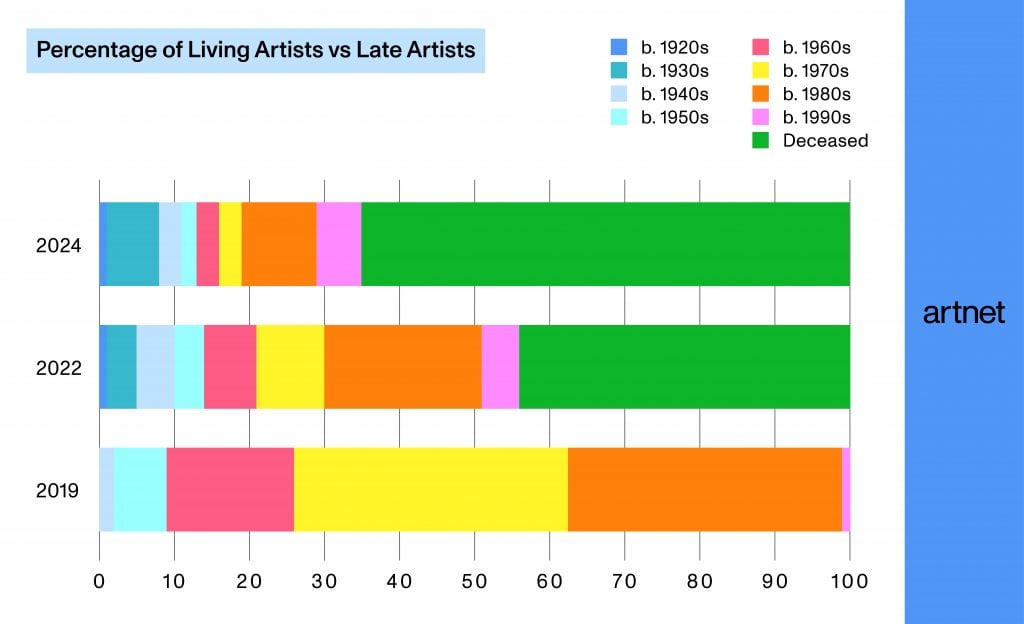

A chart showing how the ratio of living to deceased artists and the rough ages of living artists in the main exhibition has changed over the three most recent editions of the Venice Biennale. Image: Artnet.

The reduced representation of young (artists in their twenties and thirties) and middle-aged artists this year is particularly noticeable when the data on living artists is combined with that for late artists. The above chart shows that, overall, artists born after 1970 only account for about 20 percent of the total cohort selected by Pedrosa for his main exhibition.

The past decade has been an age of avid “rediscovery” within the art world as museums and galleries have attempted to rectify historical imbalances by including lesser known and overlooked artists in their collections and exhibitions. If the main exhibition at this year’s Venice Biennale is anything to go by, this era is only just beginning.