People

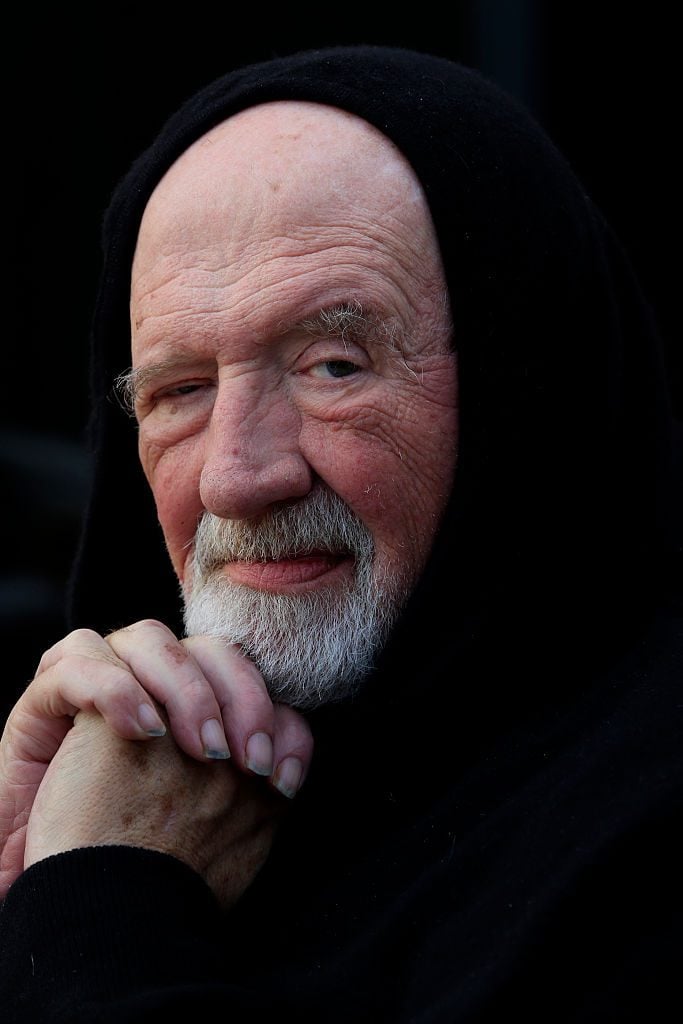

Art Critic Dave Hickey, Whose Caustic Wit and High-Meets-Low Style Made Him Essential Reading for a Generation, Has Died at Age 82

The author of landmark books such as "Air Guitar" and "Invisible Dragon" died of heart disease.

The author of landmark books such as "Air Guitar" and "Invisible Dragon" died of heart disease.

Taylor Dafoe

Dave Hickey, the influential art critic known for synthesizing high and low cultural references into divisive opinions about contemporary art, has died. He was 82.

The cause of death was heart disease, the Los Angeles Times reported. Hickey’s last moments came on November 12 at his home in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he lived with his wife, art historian Libby Lumpkin.

Known as the “bad boy of art criticism” for an iconoclastic brand of art writing forged in opposition to the academic stodginess of many of his peers, Hickey was the author of several memorable books. In 1993 came The Invisible Dragon: Four Essays on Beauty (1993), a contrarian treatise on the value of pleasurable aesthetics that became a lightning rod of controversy in the culture wars. Four years later was Air Guitar: Essays on Art and Democracy, a wide-ranging, often memoiristic collection of disquisitions on art, music, and other topics.

The latter, in particular, is regarded as one of the most important volumes of its kind. Los Angeles Times critic Cristopher Knight called it “easily the most widely read book of art criticism to appear in our time.”

Despite his disapproval of much of the insider art world, Hickey was often honored by it. He was a recipient of the College Art Association’s Frank Jewett Mather Award for art criticism in 1994, a MacArthur “genius” grant in 2001, and a Peabody Award in 2006. New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl once called him “the philosopher king of American art criticism.”

Iconoclastic art critic Dave Hickey stops in Los Angeles to talk about his new book, “Pirates and Farmers” at the ACE Hotel, January 31, 2014. Photo: Mark Boster/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images.

Born in 1938 in Fort Worth, Texas, the son of a touring musician father and painter mother, Hickey did not talk much about his childhood. He graduated from Texas Christian University in 1961 before receiving his Master’s from the University of Texas two years later. Later in the decade he did a couple of stints as an art dealer, first in a short-lived Austin gallery of his own founding called A Clean, Well Lighted Place, then at Reese Paley Gallery in New York.

In the 1970s, Hickey turned seriously to writing, serving as executive editor of Art in America. Since then, his writing has appeared in just about every major art and cultural publication, including Artforum, Harper’s, Interview, Rolling Stone, and Vanity Fair.

By the early ‘90s, Hickey gravitated toward teaching, taking on a professor role at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, before a variety of stints at Harvard, Yale, and, most recently, the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. In 2001, he curated the fourth edition of the biennial SITE Santa Fe.

Hickey claimed he was retiring in 2011, telling the Observer at the time that “most writing about art these days is so bad that my secular readership has disappeared.”

“The art world has turned nasty for some reason,” he said, “and my gentility has come out of the closet.”

R.I.P. Dave Hickey; 1940-2021

A complex leviathan, Dave used to call me up – I knew I was up for a challenge, that I would do a lot of listening, often not understanding his elaborate locution & phrasing. A great wave has passed. RIP old friend, exquisite nomad & ripening beast. pic.twitter.com/I2AG58FsDd— Jerry Saltz (@jerrysaltz) November 20, 2021

Despite this, he would go on to publish three more books: 25 Women: Essays on Their Art (2015), a compilation of writings on female artists from the last 20 years; and Wasted Words and Dust Bunnies (2016), two collections of Hickey’s musings on social media.

After news of his death went public, colleagues and fans alike memorialized Hickey on social media. Jerry Saltz called him a “complex leviathan” and an “exquisite nomad.”

“Hickey, a brilliant and cantankerous wit, wrote for the ear,” wrote Knight. “His work needed reading, not scanning, and rewarded effort with pleasure.”