Opinion

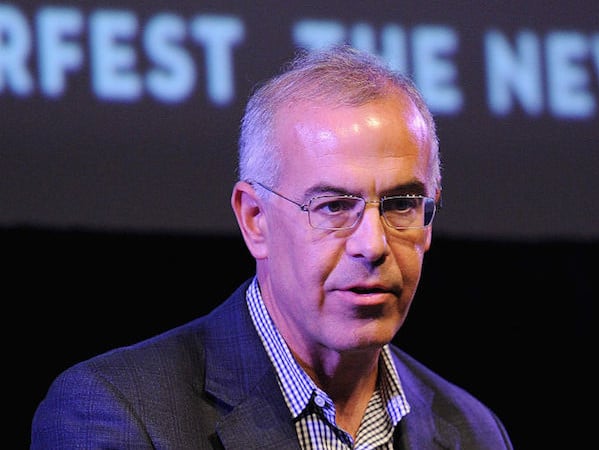

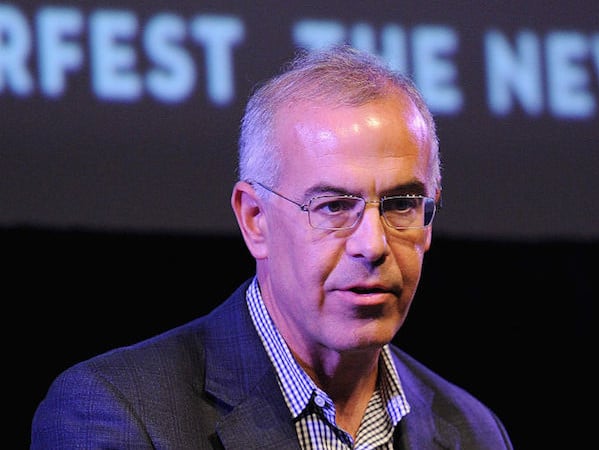

David Brooks Gets Bizarre in His Latest Essay on Beauty

The piece leaves many unanswered questions.

Credit: Bryan Bedder / Getty Images

The piece leaves many unanswered questions.

Ben Davis

Much to my surprise and delight, this past weekend New York Times op-ed maestro David Brooks took a momentary pause from his ordinary routine to weigh in on a topic that is in my direct line of sight as an art critic: contemporary notions of beauty. His column is called “When Beauty Strikes,” a title both vague and vaguely menacing.

I know at this point in history mocking Brooks is cheap sport. He’s been zinged and dinged from every which way, for his empirically dubious sociology and for his “kids these days!” conservatism, and he just keeps getting invited to be on Meet the Press.

But “When Beauty Strikes” is a particularly odd set of musings to have made it past the editor, an essay-length non sequitur. It is a doughty defense of the concept of “beauty” that leaves unanswered such basic questions as “What does David Brooks mean by beauty?” and “Why has David Brooks chosen this moment, January 2016, to pen a defense of beauty?” (Dave Hickey’s The Invisible Dragon came out almost a quarter of a century ago.)

Indeed, the closer I look at the piece, the odder it becomes. Below is the text of “When Beauty Strikes” with my annotations in bold:

Across the street from my apartment building in Washington there’s a gigantic supermarket and a CVS. As an opener, this is almost as good as that other recent David Brooks column about the election that began, “A little while ago I went rug shopping.” Above the supermarket there had been a large empty space with floor-to-ceiling windows. So many good stories begin this same way… The space was recently taken by a ballet school, so now when I step outside in the evenings I see dozens of dancers framed against the windows, doing their exercises—gracefully and often in unison. Seeing ballet lifts the spirit!

It can be arrestingly beautiful. Yes, dance is beautiful. The unexpected beauty exposes the limitations of the normal, banal streetscape I take for granted every day. Seeing ballet makes you hate your life?

But it also reminds me of a worldview, which was more common in eras more romantic than our own. When was this age of high ideals, chivalry, and elegant living? This is the view that beauty is a big, transformational thing “you see, beauty is this big… thing…,” the proper goal of art and maybe civilization itself. So far Brooks’s argument is making me wonder, “Yes, when did people stop repeating these kinds of turgid clichés about beauty?” This humanistic worldview holds that beauty conquers the deadening aspects of routine; it educates the emotions and connects us to the eternal. “Connects us to the eternal?” What on earth is he talking about? This doesn’t sound like “humanism” at all, it sounds like some vague spiritualism.

By arousing the senses, beauty arouses thought and spirit. This sounds like something a tipsy English professor would use as a pick-up line. A person who has appreciated physical grace may have a finer sense of how to move with graciousness through the tribulations of life. Or maybe the guy peeping into the ballet studio is actually a really bad life coach. A person who has appreciated the Pietà has a greater capacity for empathy, a more refined sense of the different forms of sadness and a wider awareness of the repertoire of emotions. Is Michelangelo’s reputation under some kind of threat that I am unaware of?

John O’Donohue, a modern proponent of this humanistic viewpoint, writes in his book “Beauty: The Invisible Embrace,” Great title “Some of our most wonderful memories are beautiful places where we felt immediately at home. So… our favorite memories are of things we liked? We feel most alive in the presence of the beautiful for it meets the needs of our soul. Again, this sounds like a literature professor creeping on his grad student. Without beauty the search for truth, the desire for goodness and the love of order and unity would be sterile exploits. And yet people are led to false conclusions, do bad things, and screw their life in the pursuit of beauty all the time, no? Beauty brings warmth, elegance and grandeur.” I can’t know what this hokey assertion means, because neither this quote nor the surrounding column has offered any definition of “beauty.” I gather it has something to do with the Renaissance and “feeling immediately at home.”

The art critic Frederick Turner wrote that beauty “is the highest integrative level of understanding and the most comprehensive capacity for effective action. It enables us to go with, rather than against, the deepest tendency or theme of the universe.” What kind of disguised New Age nonsense is this: beauty is the theme of the universe?

By this philosophy, beauty incites spiritual longing. Examples include: Thomas Kinkade.

Today the word eros refers to sex An unexpected new character enters the story! “Eros!”, but to the Greeks it meant the fervent desire to reach excellence and deepen the voyage of life. But we also don’t keep slaves or think that fava beans contain the souls of the dead, so we have have some things on the Greeks too. This eros is a powerful longing. “This eros is a powerful longing.” Whenever you see people doing art, whether they are amateurs at a swing dance class or a professional painter I wonder if these are really the extreme poles of acceptable ways of “doing art” for Brooks: Swing dance and painting?, you invariably see them trying to get better. You haven’t seen me swing dance. “I am seeking. I am striving. I am in it with all my heart,” Vincent van Gogh wrote. This quote is not about “beauty” or, indeed, whatever “eros” is.

Some people call eros the fierce longing for truth. Really? Because the quote you are about to use says nothing at all about “eros,” the “fierce longing for truth,” or “beauty:” “Making your unknown known is the important thing,” Georgia O’Keeffe wrote. I read that quote, think of her painting, and… heh heh. Mathematicians talk about their solutions in aesthetic terms, as beautiful or elegant. Pyromaniacs talk about fire in aesthetic terms.

Others describe eros as a more spiritual or religious longing. So “beauty” = “eros,” and “eros” = “truth” and now it also = “religious longing.” They note that beauty is numinous and fleeting, a passing experience that enlarges the soul and gives us a glimpse of the sacred. I really need some examples of what you’re talking about when you say “beautiful,” David! Please don’t make the next sentence another random quote. As the painter Paul Klee put it, “Color links us with cosmic regions.” You did it again.

These days we all like beautiful things. You mean people shop at Design Within Reach and post over-manicured selfies on Instagram? Everybody approves of art. Mozart? Star Wars? The concept of “art” in general? What “art” does “everybody” approve of? But the culture does not attach as much emotional, intellectual or spiritual weight to beauty. So, you just wish people ascribed spirituality to pretty things? Like Gwyneth Paltrow’s GOOP website? We live, as Leon Wieseltier wrote in an essay for The Times Book Review, in a post-humanist moment. Ah, a new term enters the mix! “Post-humanism.” That which can be measured with data is valorized. A minute ago, the problem was that we had lost the “desire to reach for excellence,” and now it is people wearing Fitbits. Economists are experts on happiness. We are on the same page about economists. The world is understood primarily as the product of impersonal forces; the nonmaterial dimensions of life explained by the material ones. I don’t see how “understanding” the world as the product of “impersonal forces,” which might also be called “science,” has anything to do with the appreciation of “beauty,” as the example of the mathematician who finds beauty in her proofs, 47 words earlier, suggests.

Over the past century, artists have had suspicious and varied attitudes toward beauty. Now the ponderous supertanker of this piece takes another turn, and we are tracing the vague outline of a subject for the piece: David Brooks doesn’t like contemporary art! I think? Some regard all that aesthetics-can-save-your-soul mumbo jumbo as sentimental claptrap. As they should and as it is… Because otherwise, you would be saying that… liking ballet makes you a better person? They want something grittier and more confrontational. Got it: You miss the time when art was pretty paintings. In the academy, theory washed like an avalanche over the celebration of sheer beauty Again, got it: You do not like Conceptual Art. — at least for a time. And the window is left open for a sequel, When Beauty Strikes II: The Beauty Is Back!

For some reason many artists prefer to descend to the level of us pundits. Another twist! The column is actually all about how he doesn’t like political art. And yet I can’t help but feel, in that case, that there was some example that would have been more germane as an opening than, “I was eyeing some girls doing ballet the other day…” Abandoning their natural turf, the depths of emotion, symbol, myth and the inner life, Could it be, though, that artists actually do still appreciate “the depths of emotion, symbol, myth and the inner life,” and that Brooks just doesn’t like the way they do it? Because To Pimp a Butterfly has got quite the buzz… they decided that relevance meant naked partisan stance-taking in the outer world (often in ignorance of the complexity of the evidence). A truly cowardly example-hole here. Meanwhile, how many times have you heard advocates lobby for arts funding on the grounds that it’s good for economic development? Yes: many arts advocates resort to speaking the only language that they think will get them heard.

In fact, artists have their biggest social impact when they achieve it obliquely. A powerful message rings out from the New York Times op-ed page: “Quit your marching and focus on the craft of verse, and change will eventually come.” If true racial reconciliation is achieved in this country Whoa! How did we go from the ballerinas to “racial reconciliation?” it will be through the kind of deep spiritual and emotional understanding that art can foster. … Suddenly I suspect that this column is actually all about how Ta-Nehesi Coates’s Between the World and Me is still bugging David Brooks. You change the world by changing peoples’ hearts and imaginations. I guess? But sometimes you also change the world by saying plainly that you want things to change. Meanwhile, we’ve now subtly shifted from defending “beauty” to defending “obliqueness.”

The shift to post-humanism has left the world beauty-poor and meaning-deprived. This is self-diagnosis. It’s not so much that we need more artists and bigger audiences, though that would be nice. His mind wanders and he’s thinking about how… no one goes to the symphony anymore? It’s that we accidentally abandoned a worldview When was this worldview? The 1950s? The 1850s? Biblical Times? Who is this “we?” that showed how art can be used to cultivate the fullest inner life. And we need to get that worldview back stat because Brooks really gets a kick out of those ballerinas. We left behind an ethos that reminded people of the links between the beautiful, the true and the good The non-coincidence of the “beautiful,” the “true,” and the “good” is a problem that philosophers have noted for thousands of years. — the way pleasure and love can lead to nobility. Ah, so a bold defense of the fundamental goodness of “pleasure” and “love.” Important stuff.