In recent years, queer artists—and other marginalized groups—have flocked to figuration, finding new opportunities to include representations of themselves into canons that have long disregarded them. More and more, museums and galleries, particularly in the West, are taking note and joining this correctional path toward queer visibility.

But there are many modes beyond figuration to express queer identities in art. Art historian and curator David Getsy has been observing how abstraction lends itself to often less obvious—though no less potent—ways of communicating aspects of queer experience and embodiment.

“I’ve been interested in figuring out the histories of queer art that do not immediately announce themselves as queer by playing with the ideas of abstraction, camouflage, or invisibility,” Getsy, a professor at the University of Virginia, told Artnet News.

“Queer sexuality may not open itself up to an immediate surveillance in abstraction, but rather, some practices, like cruising, operate under signals only visible for those familiar with the language,” he said.

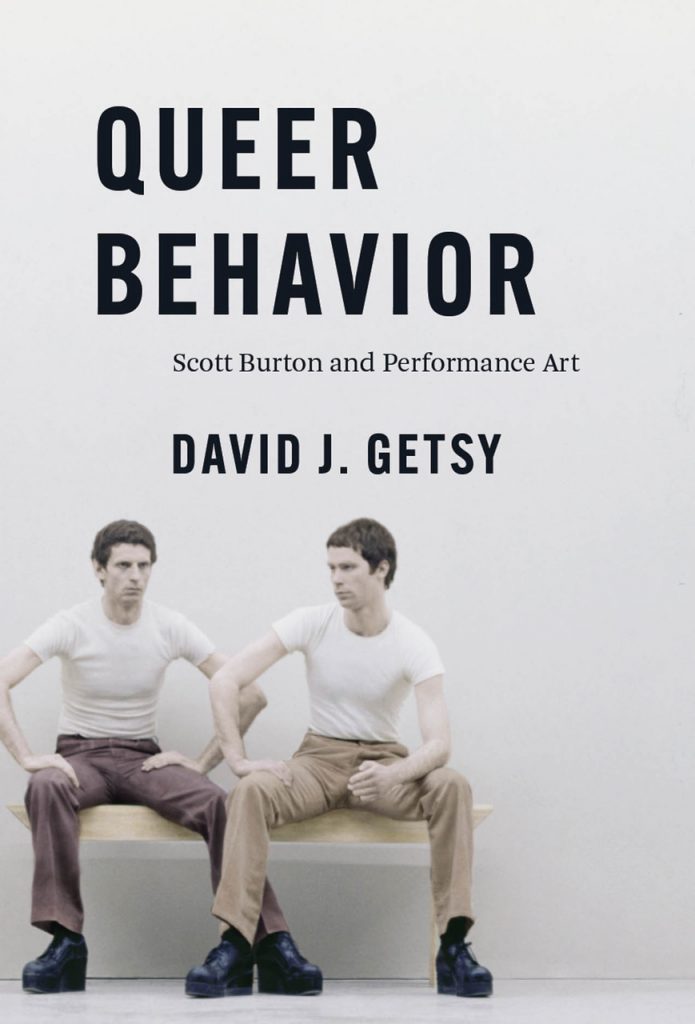

A prime example can be found in the work of the genre-defying late Conceptualist Scott Burton, who is the subject of Getsy’s forthcoming book, Queer Behavior: Scott Burton and Performance Art.

A product of the vibrant post-Stonewall scene in New York, Burton experimented with works that hid in plain sight and infiltrated institutions. Using a combination of art and function, he often solicited interactions from the public.

Burton’s performances, utilitarian furniture, and other art hybrids commanded both commercial and institutional recognition in the 1970s and ‘80s, until he died of an AIDS-related illness in 1989. (His work is part of the collections of MoMA, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Guggenheim, the National Gallery of Art, and others.)

He did not underplay the sexuality in his demurely sensual practice. Some of the artist’s steel or bronze chairs featured seats that came in in pairs, or seats for two people to sit closely together or even on top of each other, such as his economically designed Healing Chair (c. 1989). Getsy called Burton’s strategy to prompt the viewers’ (or in this case sitters’) bodies to touch, “a kind of subversive infiltration.”

At MoMA PS1’s 1976 group show “Rooms,” which also featured work by Vito Acconci, Carl Andre, and Jennifer Bartlett, Burton exhibited his mixed-media sculpture Closet Installation. The accompanying text read “Fist=Right of Freedom” and it paired the fist as a symbol of activism with the sexual act of fisting (predating Robert Mapplethorpe’s infamous photographs of same nature).

The same year, he staged the performance Pair Behavior Tableaux at the Guggenheim’s auditorium, where two male performers subtly cruised each other on a stage outfitted with a bench and two chairs.

“He delivered versions of sexuality in queer performance and art. Sometimes he was confrontational and other times he had to operate within a set of codes in order to infiltrate museum spaces,” Getsy said, referring to the widespread homophobia in the art world at the time. “The audience perhaps understood the performance’s nod to cruising but he had to find a cover to get into the institution.”

The current criticism against the commercialization of queer culture was a topic Burton spoke out against in the 1980s. “He foresaw back then what we call today homo-normativity,” said Getsy, adding that he sees the artist’s oeuvre beyond a historical moment, and as a case study for potentials in queer abstraction and performance today.

Getsy has been exploring themes of gender and abstraction for years. His 2015 book Abstract Bodies: Sixties Sculpture in the Expanded Field of Gender analyzed primarily non-queer and non-trans abstractionists, such as Dan Flavin and John Chamberlain, but asks, “how abstraction could inadvertently produce accounts of gender as multiple or transformable.”

Studying abstract sculptures from the 1960s led Getsy to realize “how there is a productive interplay between artists who are trying to not represent the body at all and the ways in which the physical traits of sculpture nevertheless leads them to associate it with questions of embodiment, or their own bodies or their physical presence.”

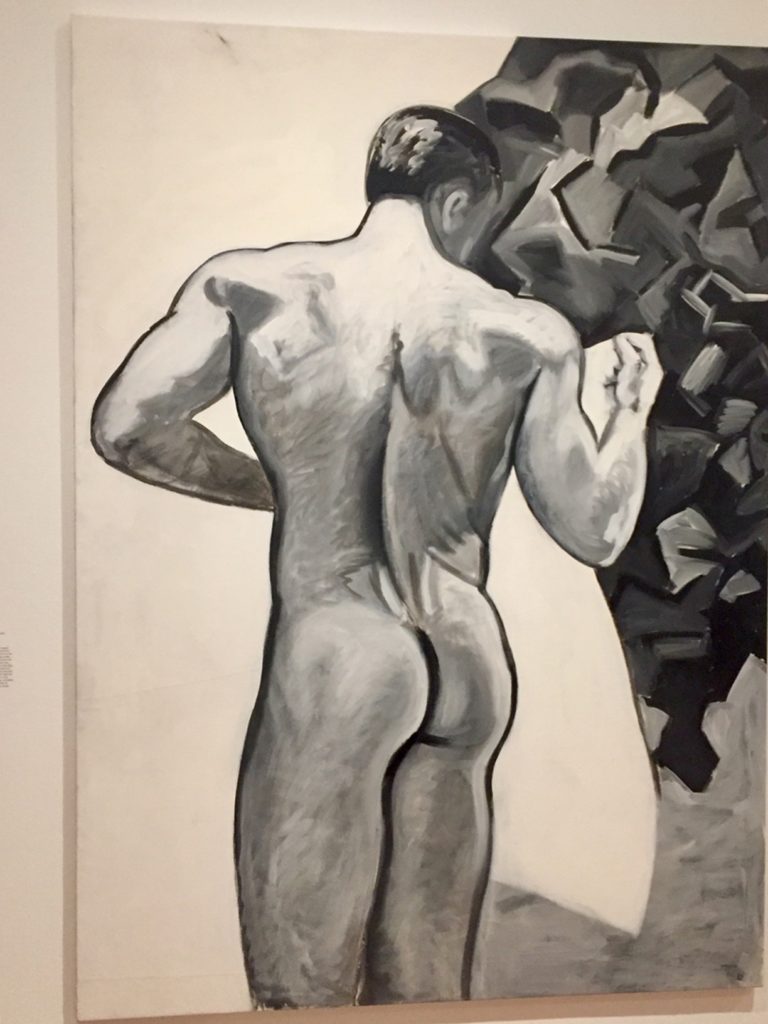

Mundo Meza’s Untitled (Male nude) (c. 1983). Photo: Ben Davis.

The particularity of the figurative image, he notes, could be “limiting” for artists whose work inherently challenge image-based categorization.

In recent decades, queer and non-binary artists such as Harmony Hammond, Lula Mae Blocton, Carrie Yamaoka, and Mundo Meza, have used similar visual strategies to maneuver tokenization. Yamaoka’s densely tactile, almost sweaty mylar surfaces or Hammond’s abstract drawings made with menstrual blood for example encapsulate a body’s experiences without the likeness of one.

They “have been pursuing different degrees of abstraction,” Getsy said, allowing them to avoid potential figurative pitfalls, “such as objectification of the body and the question of what constitutes an erotically available body.”

Still, even certain forms of abstraction can be turned into easy symbols for institutions looking to signal queer content. Getsy points the example of the rainbow, a form of color geometry at its core and an instantly recognizable icon of queer identity. “No longer abstract, the constantly recycled image eventually evacuates its original intentions of desire and kinship towards becoming a palatable standard for corporations,” he said.

Some artists are embracing technology as a queer art making practice that offers alternative potentials for bodily representation. Screens, apps, games, and glitches provide new means of rendering corporeal experiences, including ones that evoke “the embodiment or interpersonal relations that don’t rely on the figurative image alone,” Getsy said.

A visitor uses a virtual reality headset to view the artwork of Jacolby Satterwhite “Domestika” during the press preview for Art Basel in 2018. Photo by Harold Cunningham/Getty Images.

He cites Jacolby Satterwhite as an example of an artist who “has been playing with available imagery through gaming technologies and interacting with desire in radical ways.”

Despite the many modes artists are using to understand the multiplicity of genders and sexualities through art, institutions are still lagging behind. In some cases, their attempts at inclusivity feel tenuous, and Getsy wonders whether they will be sustained.

“In addition to evident signals such as re-writing the wall labels, some museums have also taken on the ‘less sexy’ but important effort to rethink their databases based on current gender pronouns and truthful biographies,” he said. “However, there is still a relatively small number of queer, and especially trans, artists that museums are relying upon, which shows a hesitance toward opening up larger conversations around the subjects.”

Getsy asks the public and its institutions to grasp new alternatives that embrace multiplicity. “I’m interested in understanding that gender is as transformable as it is multiple, not limited to static options, and this implicates everything and everyone in a different way.”