It has been a year of celebration for the 80-year-old painter David Hockney, whose retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art opens next week. While in town, the artist gave a talk at the Film Society of Lincoln Center after a screening of his recently remastered 1998 documentary A Day on the Grand Canal with the Emperor of China, or: Surface Is Illusion But So Is Depth, directed by Philip Haas.

After the film, Hockney and Haas discussed perspective, technology, and Brexit (“I really couldn’t care less” was Hockney’s response to the stay-or-go question). The artist also elaborated on his years-long obsession with reverse perspective, which he first encountered in Chinese scrolls just before making the film. This preoccupation is evident in Hockney’s own work, which shifts and skews perspective, and most recently in his rectangular canvases with the edges cut off. “Now I’m into reverse perspective,” he said. “I cut the corners off—I’m doing it really, really good now.”

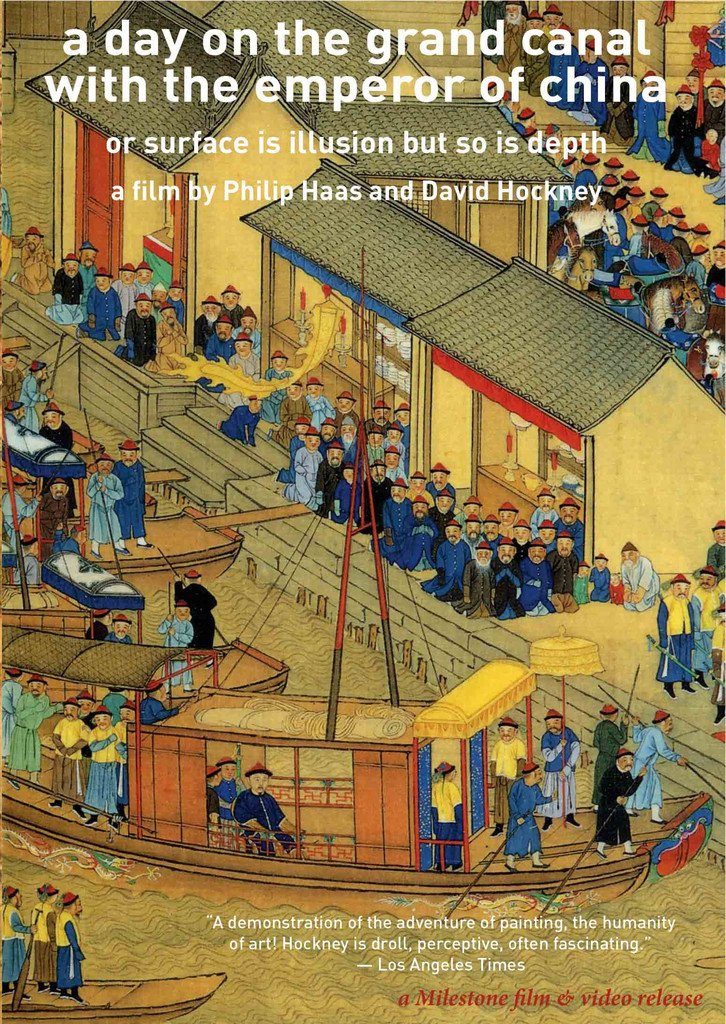

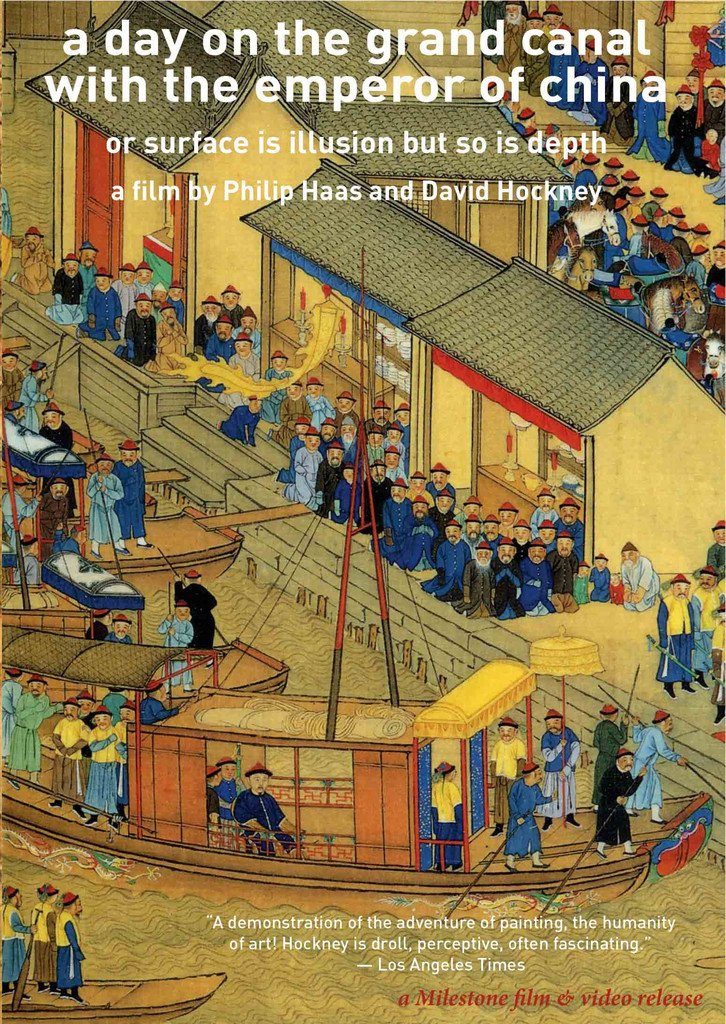

Philip Haas and David Hockney’s A Day on the Grand Canal with the Emperor of China (1998), Courtesy of Milestone.

In the short film, Hockney acts—in his own estimation—as a poor imitation of the superlative art historian Kenneth Clark, taking the viewer through an analysis of a 17th-century Chinese scroll painting by Wang Hui that predates the introduction of Western perspective to Asia. He proves a charming narrator, pointing out his favorite details: “There’s even a monk that looks like my good friend Henry Geldzahler!”

As a counterpoint to Hui’s scroll, Hockney refers to what he calls “the evil Canaletto,” an 18th-century painting by the Italian artist that demonstrates the use of a single vanishing point. Although later Hockney clarifies that the Canaletto is actually quite good, it serves to illustrate the “tyranny of vanishing-point perspective,” an issue which he has doggedly pursued throughout his career. In 2001 he published a book, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, in which he argues that long before the invention of the camera lucida, artists were relying on optical devices to illustrate a vanishing point.

Artist David Hockney poses with his painting Studio Interior #4 2014-2015. Photo: Leon Neal/AFP/Getty Images.

Hockney is interested in any technology that relates to picture making, from his own use of the iPad to Chinese museums that have begun to animate historic scrolls for more engaged viewing. As for photography, “Edvard Munch said, ‘it can’t compete with painting, because it can’t deal with heaven or hell’ which is rather profound,” he told the audience. But Hockney draws the line at virtual reality: “It’s not that good,” he said. “I think it will be very good for pornography, but that’s about it.”