People

Hockney’s Children: 5 Artists on Why They’re So Indebted to the Charming British Painter

Jonas Wood, Jordan Casteel, and others describe how early encounters with Hockney transformed their approach to painting.

Jonas Wood, Jordan Casteel, and others describe how early encounters with Hockney transformed their approach to painting.

Sara Roffino

Beloved for his bold colors, brilliant brushstrokes, and preternatural fashion sense, David Hockney is celebrating his 80th birthday this year with a traveling retrospective that is now on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The Bradford-born painter, whose iconic images of Southern California have come to define an entire geographic region, has enjoyed a rare combination of both popular adoration and critical acclaim.

Naysayers, however, are out there. The most rampant charge leveled against Hockney is his work’s inherent pleasantness and likability. To some of his critics, winsomeness and seriousness are inherently incompatible.

Other jabs have more to do with Hockney’s titanic stature than the quality of the work itself. Writing in the Independent earlier this year, British critic Michael Glover made a baldly classist dig: “What could the reasons possibly be for the fact that every plumber, every pen-fiddler, has his Hockney favorite, that all that idle Hockney banter needs to be cranked up all over again?”

But critics aside, Hockney’s true legacy will likely be judged by his influence. And a variety of painters have plenty to say—and plenty to admire—about the British artist. From his brilliant use of color to his early and radical depiction of queer life to his multi-perspectival approach to the canvas and his unceasing experimentation with technology, Hockney’s impact can be seen in countless painters spanning multiple generations. Below, we speak to five of them, ranging in age from 69 to 28.

Fischl started out in the 1960s trying to make abstract paintings. When his attention turned to figurative and narrative work, Hockney loomed large as both a reference and challenge.

Eric Fischl’s Feeding the Turtle (2016). Courtesy of the artist and Skarstedt, New York.

“Hockney’s works became touchstones,” Fischl recalls. “But they also became irritating because he casts a big shadow in terms of strategies for making paintings, representation, drawing, color, and subject matter. I was trying to figure out how to paint people sitting around a swimming pool in the suburbs, and I had to go through Hockney’s representation of water to get there because he named water. He named pools, he named sprinklers on a lawn, he named palm trees, he named reflections in bay windows.”

David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) (1963). David Hockney/ Art Gallery of New South Wales / Jenni Carter.

Fischl acknowledges that his works, while examining similar subjects, are fraught where Hockney is more upbeat. His paintings “are more like the underbelly of Hockney’s world,” he says. The inherent joy in a Hockney painting can be jarring to American eyes. As Fischl explains: “His sense of color and beauty is so unabashed in a way that… challenges an American sensibility, which thinks that maybe there’s something wrong with pleasure, that you should be more distrustful of it.”

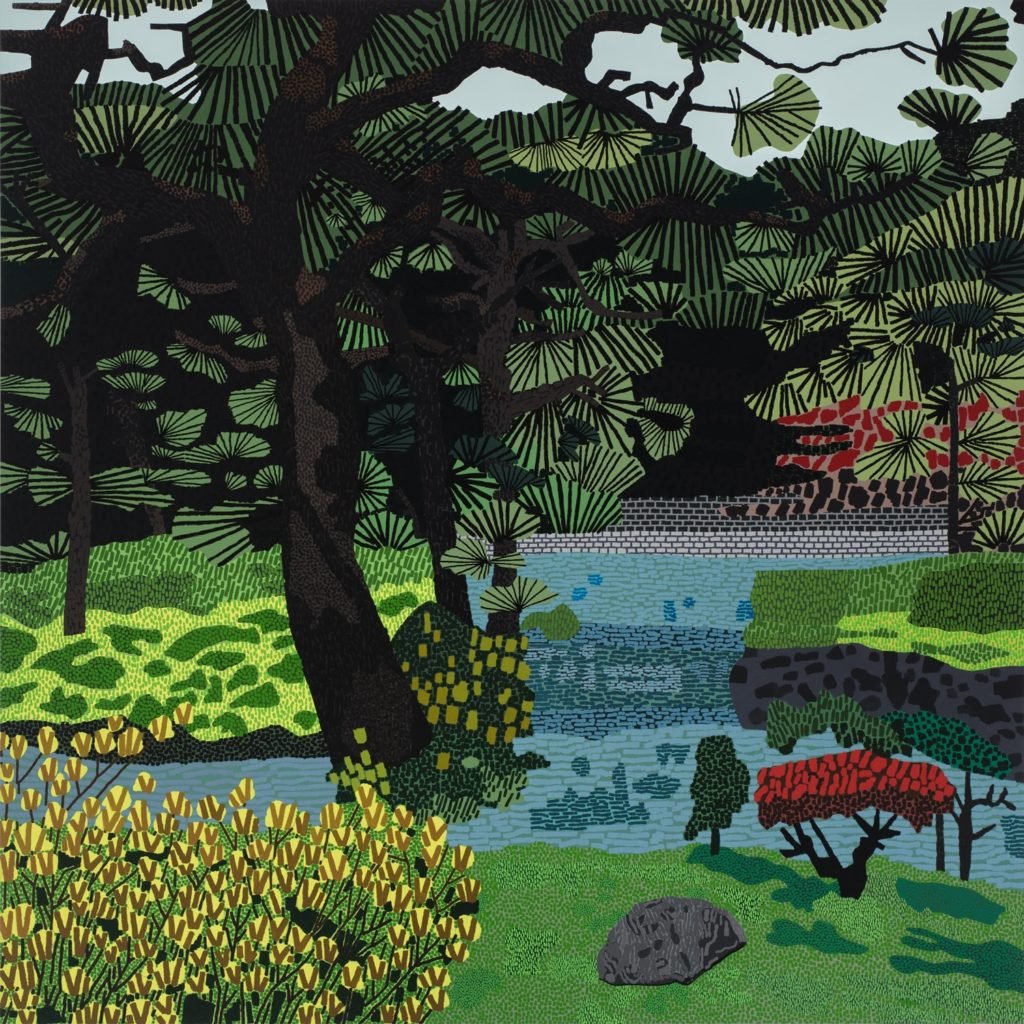

Picking up Hockney’s torch of California cool, the Los Angeles-based Wood—known for his depictions of lush So-Cal interiors and exteriors—is perhaps the artist’s most direct descendant working today.

Jonas Wood’s Japanese Garden (2017). Courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery.

Though he was first introduced to the British artist as a teenager, Wood didn’t begin making paintings of his own in earnest until his early 20s. At that point, he says, “my interest in Hockney came out of being interested in Modern painting and Picasso and Braque. Obviously, Hockney painted from that place in a way too. He went through a whole Cubist thing and in some of his early work there’s a Bacon influence as well. You can put Hockney together as a conglomeration of all of my favorite Modern painters.”

David Hockney, Garden (2015). © David Hockney. Photo Credit: Richard Schmidt.

Wood says he and Hockney also share an interest in combining multiple perspectives, using patterns to create space, and examining how color “can be irrational and rational at the same time.” As Wood puts it: “Hockney veers into the extreme abstract, but still holds onto the thread of representation. He’s always pushed the boundaries as a representational painter. That’s why I’m drawn to him—because of this constant invention.”

Heidkamp, who is best known for his historically engaged contemporary landscapes often made en plein air, describes his influences as “French Impressionism filtered through American painting like Edward Hopper and Fairfield Porter.” Yet, he says, “I can’t think of a time when I wasn’t aware of Hockney of some level.”

Daniel Heidkamp’s Dawn Watcher (2017). Courtesy of the artist.

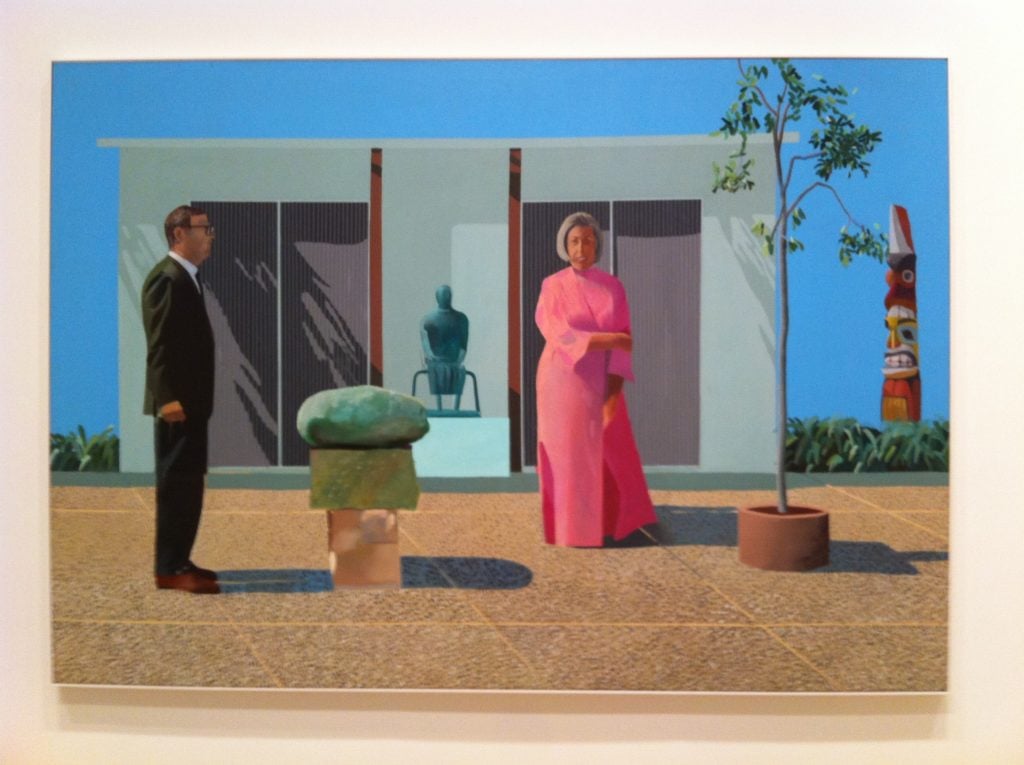

The artist, whose iPhone photo exchange with fellow painter Cynthia Daignault is on view in the Met’s exhibition “Taking Pictures: Camera-Phone Conversations Between Artists,” recalls early encounters with two Hockney works in particular: Garrowby Hill (1998) at the MFA Boston and American Collectors (1968) at the Art Institute of Chicago.

“In different ways, both paintings offered access to strange realms beyond the normal visual field, and provided clues about what was really going on behind the scenes for the artist,” he explains. “When digging into Hockney, it quickly becomes apparent that he has covered all of painting’s most fertile ground—landscape, portraiture, abstraction, Pop, and Picasso.”

David Hockney, American Collectors (Fred and Marcia Weisman) (1968). Courtesy of Flickr.

Heidkamp says Hockney’s wide-ranging style helps illuminate unlikely connections between artists as disparate as Martin Kippenberger and Alex Katz. “In some ways he is the elephant-sized master in the room,” he says.

Heidkamp has long been interested in exploring space and dimension, and has been particularly drawn to Hockney’s rendering of deep space and flat leafy ground in his recent Yorkshire landscapes. “These strike a chord with me because they serve as contemporary updates for spatial issues that have been explored throughout art history and famously in paintings such as Bellini’s Madonna of the Meadow,” he says.

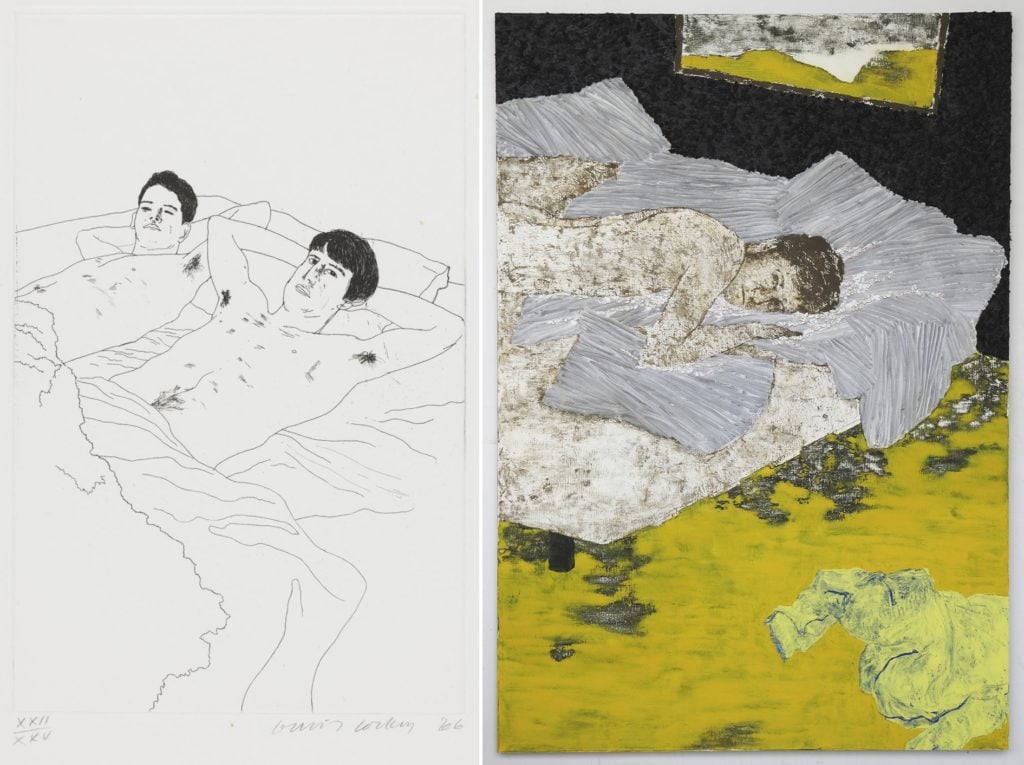

“Hockney has been with me for most of my artistic life,” says Israeli-born, New York-based Langberg, known for his intimate portraits of friends and nude men. Though he doesn’t recall the specific moment he first encountered the elder artist, “the thing that was most striking was the way he offered an everyday, intimate view into queer life. I felt like I could inhabit that space, it was so relatable. He’s a master draughtsman and his gaze is a democratic lens that describes these beautiful intimate moments.”

L: David Hockney’s Despair (1966). © David Hockney, courtesy of Tate.

R: Doron Langberg’s Tehura (2012). Courtesy of the artist.

Langberg was particularly encouraged by Hockney’s ability to move freely between styles and subject matter. If Hockney could explore these subjects without getting pigeonholed, he thought, maybe he could, too.

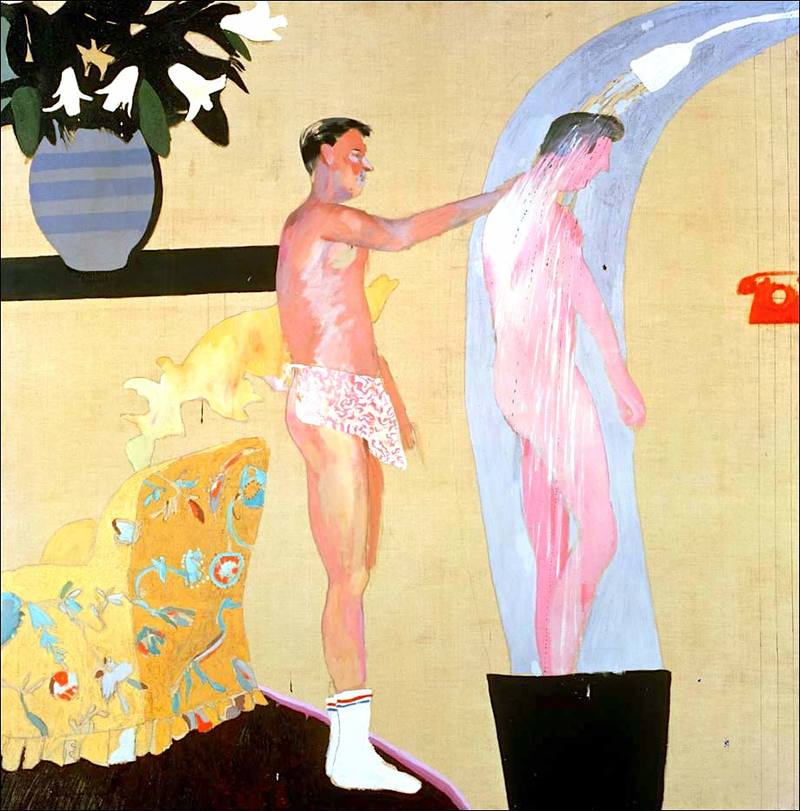

David Hockney’s Domestic Interior, Los Angeles (1963). © David Hockney, courtesy of Tate.

“Earlier on, when I working with more explicitly queer content, there was a hesitancy: am I supposed to represent a whole group of people? I wanted to make work from that place, but I also didn’t want to stereotype myself,” Langberg says. “All these issues of representation and perception come up when you’re working from a queer viewpoint. You don’t want to be defined by it. I don’t want to be a gay painter, I just want to be a painter, but I’m gay and these issues are important to me and I feel like they dominate my life in so many ways—how can they not dominate my work? Looking at Hockney and how at ease he is with his subject matter and the way that he depicts it is so inspiring.”

Since graduating from the Yale School of Art in 2014, Casteel has risen quickly to acclaim in just a few short years with a Studio Museum residency and shows at Sargent’s Daughters and Casey Kaplan. She says that her portraits of black men, which address issues of masculinity, were enriched by her introduction to Hockney.

Jordan Casteel, Cowboy E., Sean Cross, and Og Jabar (2017). Photo: Jason Wyche, courtesy the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York.

While in school, someone suggested she take a look at his palette. “I remember finding a book of his in the library and I was flabbergasted,” she says. “I was really excited by the use of color and how it felt like his eye was dictating the way that I was seeing what he was seeing. I started using paintings of his to create palettes for my own paintings.”

Casteel’s method of working also owes something to Hockney’s use of technology. Like the British painter, Casteel takes multiple images of the same space and then constructs a composite of those images in her compositions. “Multitudes of images help [me] see something differently,” she notes.

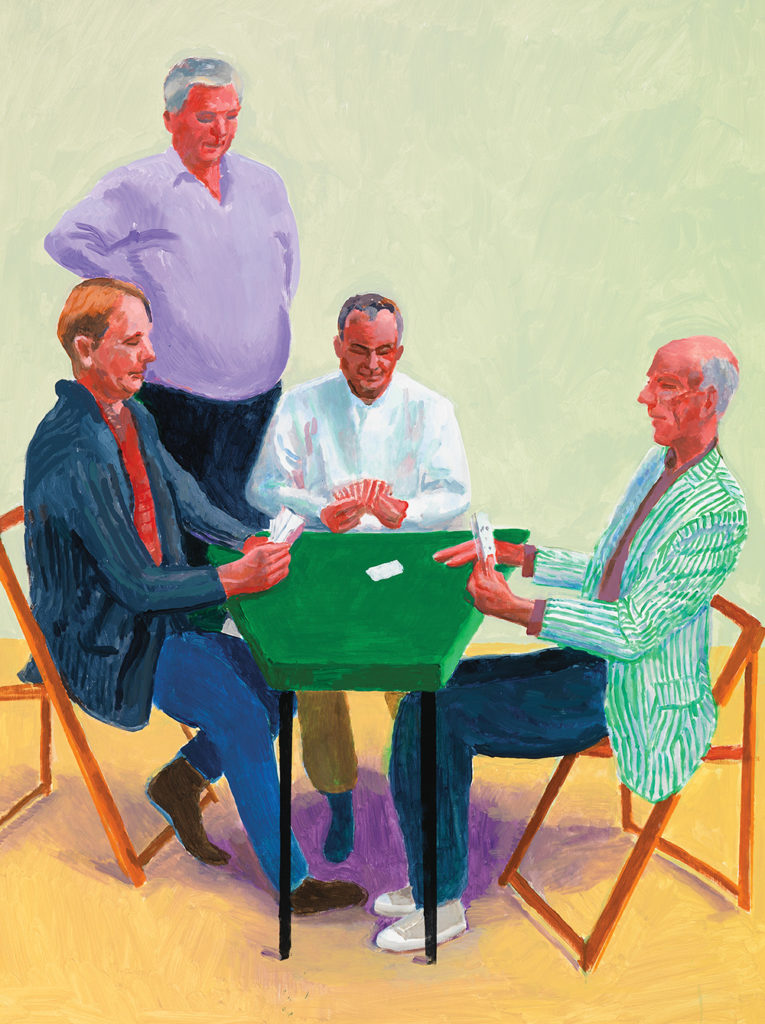

David Hockney, Card Players #3 (2014). © David Hockney. Photo Credit: Richard Schmidt.

While Hockney focused his gaze on the gay community, Casteel examines the men in her life as well as those in Harlem, where she lives. “Hockney’s paintings become a liaison into his world—and he took a community that’s not well understood by the general public and normalized or humanized people who were oftentimes otherwise ostracized and misunderstood.”

David Hockney is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York until February 25.