On View

David Hockney Opens Up About the Tragedy That Triggered His Return to Portraiture

He is the subject of an exhibition at London's Royal Academy of Arts.

He is the subject of an exhibition at London's Royal Academy of Arts.

Naomi Rea

British artist and septuagenarian David Hockney has never been one for predictability. The outspoken artist is about to turn 79, and next year’s retrospective at the Tate will showcase the ceaseless experimentation that has spanned throughout his career.

But the series of portraits that will be exhibited to the public at the Royal Academy from July 2 captures a very specific time in the artist’s life.

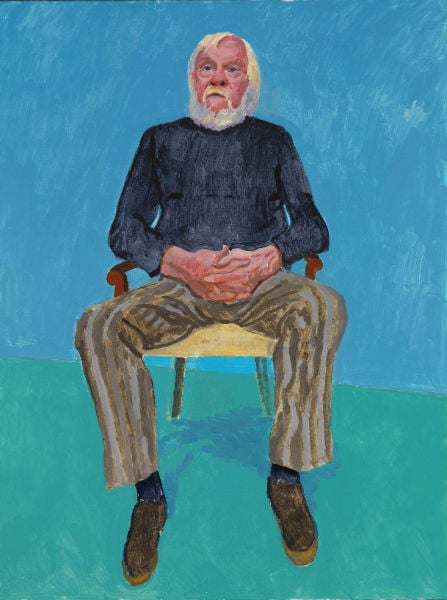

Rufus Hale, 23rd, 24th, 25th November 2015 ©David Hockney. Photo Richard Schmidt.

Over the last three years, the Royal Academician has returned his focus to portraiture, producing an astonishing body of work. Each of the 82 portraits that make up the series were composed in his Los Angeles studio, where Hockney retreated after the accidental death of his young assistant and close friend Dominic Elliot in 2013, at the artist’s home in Bridlington.

In an interview with the BBC’s Will Gompertz, Hockney speaks of the depression and creative difficulties he had following the incident. “That was a terrible shock, I mean a terrible thing. I didn’t do much work for a while, I mean I just… I drew the garden.”

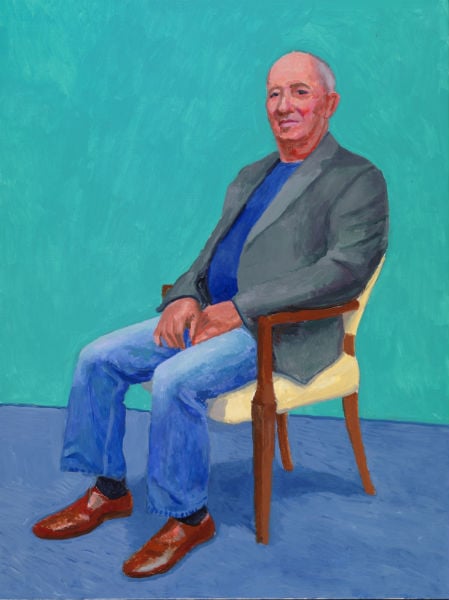

John Baldessari, 13th, 16th December, 2013 ©David Hockney. Photo Richard Schmidt.

After a long silence, Hockney managed to create a portrait of his studio assistant and friend, Jean-Pierre Gonçalves de Lima (JP), which became the first portrait of the series. It captures JP, who was equally devastated by Elliot’s death, sitting inconsolable, head buried in his hands. The painting seems to have been cathartic as it prompted a reignited Hockney to create the series.

This is not surprising, as time and again we have seen key moments in Hockney’s life prompt an emotional response in his work. Whether it’s painful break ups, the trauma of the AIDS epidemic in the late 80s, or personal grief, portraiture seems to be somewhat of a sanctuary for the artist.

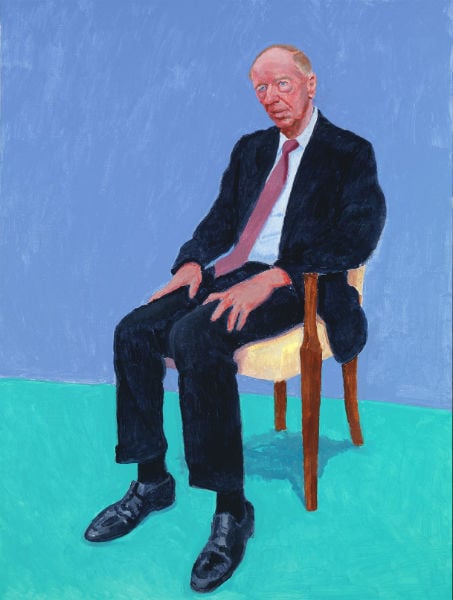

David Juda, 22nd, 23rd, 25th March 2015 ©David Hockney. Photo Richard Schmidt.

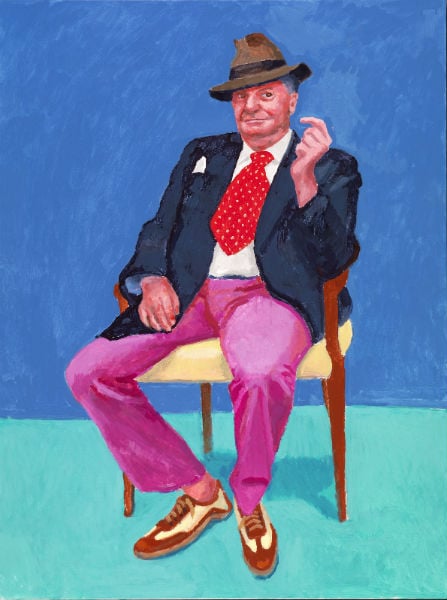

The rest of the portraits are of Hockney’s family and friends, and each conveys a sense of the personality of the sitters that can only be borne from intimacy. Each subject was invited by the artist to sit for him, and those depicted include John Baldessari, Larry Gagosian, Frank Gehry, and Lord Rothschild, as well as Hockney’s siblings, John and Margaret.

Rita Pynoos, 1st, 2nd March 2014 ©David Hockney. Photo Richard Schmidt.

Looked at together, there are visual similarities in all of the pieces: each subject is captured in swatches of bright colours on canvases of the same size, each sitter is painted in the same chair, and each work relays an uncanny dual sense of looking through both one’s own, and Hockney’s, eyes.

But the similarity ends there. Although they might all be colored by Hockney’s perspective, each sitter also manages to preserve their own internal life the viewer doesn’t quite have access to.

Jacob Rothschild, 5th, 6th February 2014 ©David Hockney. Photo Richard Schmidt.

Hockney considers all 82 portraits and the still life to make up a single body of work. The series, according to the artist, is about how “we’re all individuals. That’s what it tells us. That we’re different on the outside, we’re different on the inside.”

Barry Humphries, 26th, 27th, 28th March 2015 ©David Hockney. Photo Richard Schmidt.

David Hockney “82 Portraits and 1 Still-Life” is on view at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, from July 2–October 2, 2016.