Art World

How Social Practice Artists Are Using Creative Problem-Solving to Help Revive Detroit

From urban chickens to park rehabilitation, artists are coming up with interesting ways to solve problems in Motor City.

From urban chickens to park rehabilitation, artists are coming up with interesting ways to solve problems in Motor City.

Brian Boucher

Detroit’s Eliza Howell Park, one of the city’s largest, rambles across some 250 acres. The park thrived decades ago, but as the city descended into economic depression, prostitutes and drug dealers became sights as common as the roaming muskrats, minks, and coyotes.

A nearby artist coalition, Sidewalk Detroit, is pairing artists with residents to create artwork and infrastructure in the park with the hopes that the city will partner in those efforts.

The huge wildlife preserve and nascent art venue serves as a microcosm of the possibilities and challenges that social practice art in Detroit offers. With just 700,000 people spread out over some 140 square miles, and with strong support from philanthropic organizations like the Knight and Kresge Foundations, Detroit provides fertile soil for a growing art scene.

Juliana Fulton designed a sign educating visitors about the history of Eliza Howell Park. Courtesy of Sidewalk Project.

There’s abundant and still relatively affordable space. There’s an avid and receptive audience. And there are daunting, urgent social and infrastructure needs that local communities and artists can help meet.

In the case of Eliza Howell, there’s a catch-22: the city hasn’t installed basic infrastructure like lighting and bathrooms in the park because locals don’t use it; the locals say that that’s because there aren’t those basic amenities. So artists, with the support of philanthropists and foundations, stepped into the breach.

Oakland Avenue Urban Farm. Via Twitter.

Similarly addressing urgent human needs is the Oakland Avenue Urban Farm, in Detroit’s North End. Founded by Billy and Jerry Hebron, who previously worked in real estate, the project brings together several local organizations: the architecture firm Akoaki, art and music venue One Mile Project, and the nonprofit Center for Community-Based Enterprise. The organization is developing a five-acre complex that will integrate housing, urban farms, a hostel for visiting artists, and an art venue.

Seeking to establish a strong and lasting foothold, the organizations have worked together to buy up plots of real estate and turn them over to a community trust. The existing gardens provide produce that Oakland Avenue sells to workers at the local Daimler-Chrysler plant, where healthy food is scarce, and to the city’s open-air Eastern Market. The organization received a $500,000 “creative placemaking” grant from ArtPlace America in 2016.

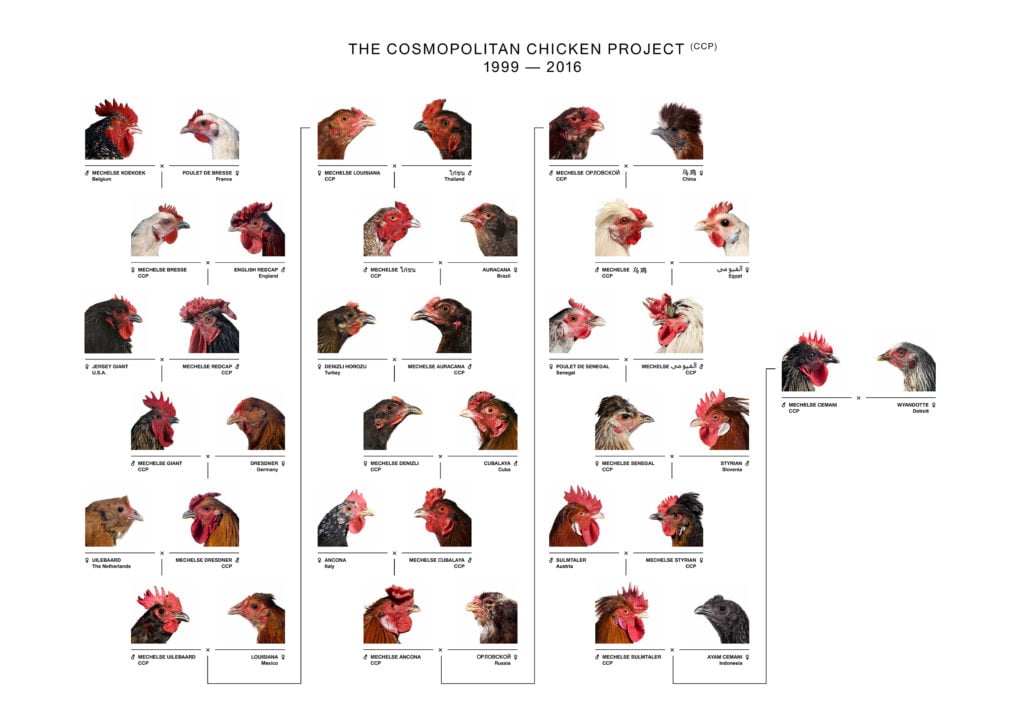

Koen Vanmechelen’s Cosmopolitan Chicken pedigree. Courtesy of the Wasserman Projects.

Food and art are even more closely intertwined in another commodity offered at the Oakland Avenue Urban Farm: eggs from chickens bred by Belgian artist Koen Vanmechelen as part of his practice. Vanmechelen’s Cosmpolitan Chicken Project is supported by local art dealer Gary Wasserman, of Wasserman Projects, a contemporary art venue in the Eastern Market neighborhood.

Koen Vanmechelen, Material World (2016). Courtesy of the Wasserman Projects. Photo by PD Rearick.

A hybrid developed by the artist to bring together desirable qualities of several varieties of fowl, the Cosmopolitan Chicken serves as a metaphor for the benefits of diversity in the human gene pool. In the future, the birds’ meat will also be for sale. “It’s the most esoteric art combined with the most basic human need,” Wasserman said, acknowledging that the artist’s more market-ready products—including taxidermied chickens and animal portraits—remain a tough sell for locals.

Turning the tables on traditional power structures, the Ghana Think Tank looks to people in places like Sudan, Cuba, and Iran to help solve first world problems. The group was founded in 2006 by Christopher Robbins, John Ewing and Matey Odonkor; Maria Del Carmen Montoya joined in 2009. They surveyed Westerners who they say complained of feeling disconnected from their neighbors. In response, Moroccan consultants offered a solution, pointing out that their own living structures are often centered around a courtyard where one inevitably crosses paths with one’s neighbors. Thus was born an architectural project they called the American Riad, a metal structure incised with geometric Islamic designs that provides a covered space between two houses. The project is in collaboration with Oakland Avenue Artist Coalition, Central Detroit Christian CDC, and NEWCO (North End Woodward Community Organization).

Rendering of the Islamic Riad, a shared courtyard that will join repaired homes and businesses. Courtesy of Ghana Think Tank.

“The American RIAD project grew out of widespread social isolation,” said Montoya. “People have a concept of post-apocalyptic Detroit and its loss of infrastructure and social services. Neighborhoods have become increasingly de-populated, so there’s little possibility for community. We’re trying to generate community by creating a place where people can share time and space and ideas, as well as compensate for the loss of collective memory about these neighborhoods.”

Pope.L, Flint Water installation view (2017). © Pope.L

For his recent project at the Detroit gallery What Pipeline, artist Pope.L is selling bottles of lead-poisoned tap water from Flint, with all proceeds going to provide clean water for the city, recasting Detroiters into the role of saviors rather than the saved.

The enthusiasm for social practice has also taken root at the city’s Red Bull House of Art (funded by the energy drink company), which is planning a round of residencies for artists working in social practice, director and curator Matt Eaton said during a visit to Red Bull’s studio and gallery building near Eastern Market.

Ingrid LaFleur, an artist and curator who recently ran (unsuccessfully) in Detroit’s recent mayoral election, pointed out that in light of the urgent needs of the populace, there are abundant opportunities for artists to practice creative problem solving. In fact, she pointed out, the term “social practice” seems too constricting for what artists are doing in the Motor City. She quoted Bryce Detroit, who organizes music and cultural programs at One Mile, as saying, “This isn’t social practice—it’s survival.”

Even as Detroit remains, in many neighborhoods, stricken with neglect, the days of $500 houses are gone, with not just local but international developers swooping in. So how do artists and their allies in community development avoid becoming the tip of the spear of gentrification?

“Everyone’s trying to figure that out,” says LaFleur. “It’s a work in progress.” Speaking to a group of visitors at local arts venue One Mile, on a tour of the city organized by the nonprofit Culture Lab Detroit, architect Anya Sirota mentioned that they all heard warning bells when a Craigslist real estate ad used the venue as a selling point, boasting of being “just steps from One Mile.” As a result, the artistic community is trying to think long-term, said Sirota, and buy up land to donate to community trusts, so that no one can cash out to the detriment of locals.

Myers-Johnson says developers buying in Brightmoor should invite area representatives into a dialogue to “develop community benefits agreements and solidify contracts that develop the neighborhood in an equitable way.”

The city’s future and viability for working citizens may depend on such innovative arrangements. Many locals say that for a revival to happen, the city needs to develop industries to replace the careers lost with the collapse of the auto industry.

Wasserman warns against what he calls an oversimplified vision of a future that in some way reproduces the past. “This is not a ‘renaissance’ story,” he says. “This is not going to be the Detroit of the 1950s, so rid yourself of preconceptions. There will have to be some new model of a city.”