On View

Did Claude Monet Learn His Extraordinary Use of Color From His Brother, a Pigment Chemist? A New Show Looks at the Influence of Léon Monet

The show includes never before seen paintings by Monet, as well as his adolescent sketchbooks.

The show includes never before seen paintings by Monet, as well as his adolescent sketchbooks.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

Léon Monet was born in 1836, four years before his younger, more famous brother Claude, and he took a very different path in life. After studying to become a chemist, he moved to Rouen where he specialized in the production of synthetic pigments to be used as dyes, eventually becoming a founding member of the Rouen Industrial Society.

Luckily for Claude, this growing industry was well paid and Léon was able to offer his brother some financial support long before he gained widespread recognition, even introducing him to a few of his rich friends. Taking his interest in Claude’s work a step further, Léon began attending exhibitions in Paris and Rouen and collected paintings by other Impressionists including Renoir, Sisley and Pissarro.

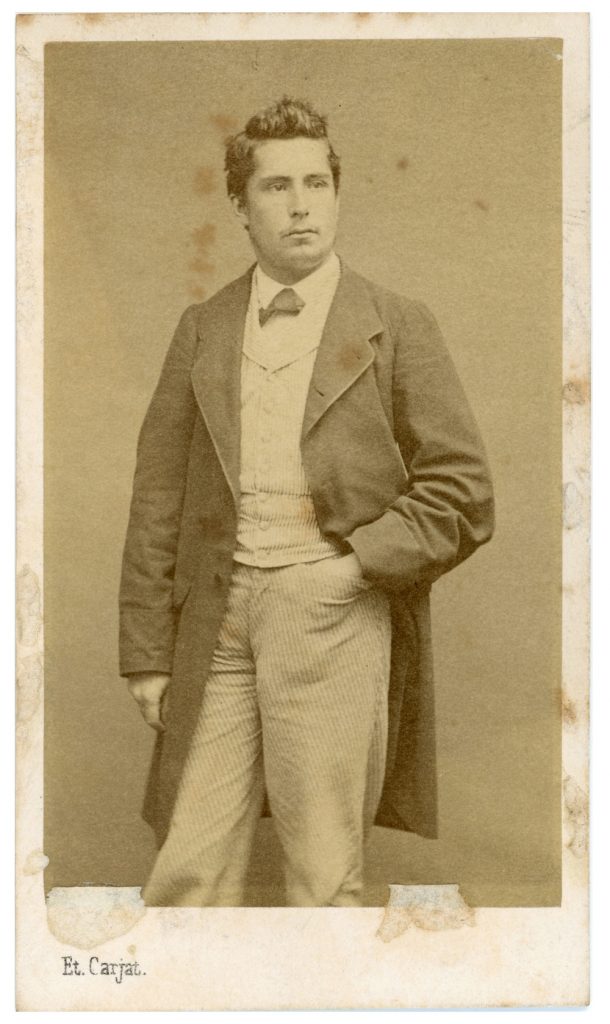

Etienne-Carjat & Cie, Portrait of Léon Monet. Photo courtesy of Musée du Luxembourg.

The exhibition, “Léon Monet, artist’s brother and collector”, which runs until July 16 at the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris, sheds new light on Léon’s little known role as a supporter of the Impressionist movement as well as his relationship with his brother, which may have been more creative than most would assume.

“Léon was a chemist of synthetic colors, and these became increasingly common in painting at the end of the 19th century,” the show’s curator Géraldine Lefebvre told Artnet News. “I think he played a key role in this new way of painting and pushed his brother to use new colors.”

Though the pair were close for many decades, they had sadly fell out by the time of Léon’s death in 1917. Check out a tour of some of the artworks and objects that he collected over his lifetime below.

First notebook of drawings by Monet from 1856, acquired by Léon in 1893. Photo: © François Doury.

Never before seen by the public, one of the most exciting works included in the show is one of Claude’s earliest sketch books, which he started in 1856 at the young age of 15. Léon acquired the book at auction many years later in 1893 and one page bears a personal inscription by Claude written in 1895.

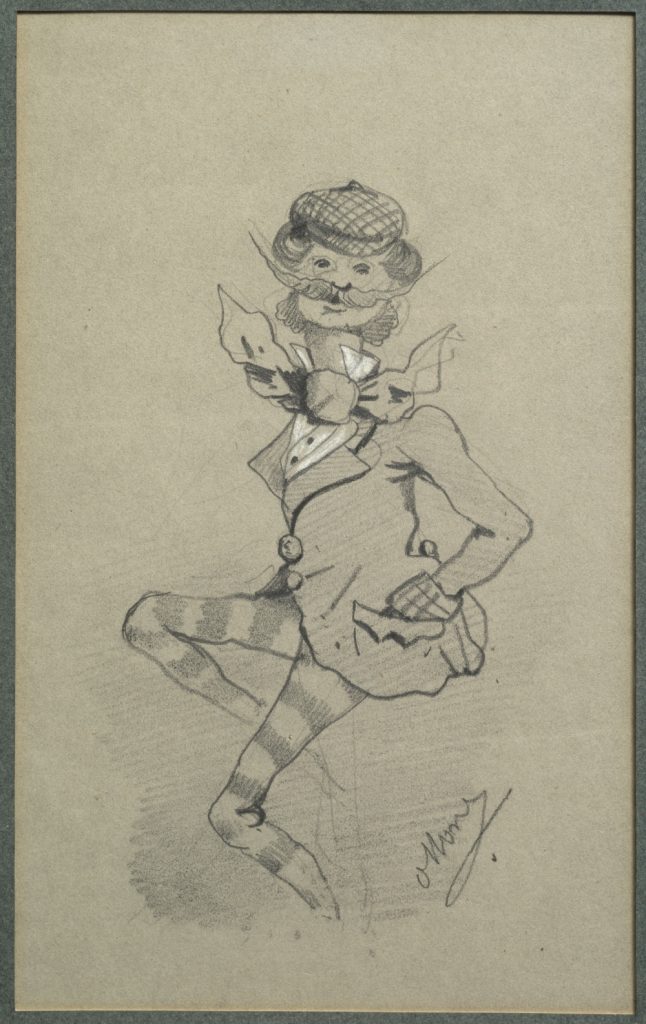

Around this time, Claude also produced caricatures to sell for pocket money. One image of a bourgeois figure with an exaggerated moustache and bowtie and fancy striped pants was originally bought by Léon’s close friend Ernest Billecocq.

Claude Monet, Anglais à moustache (c.1857). Photo courtesy of Musée du Luxembourg.

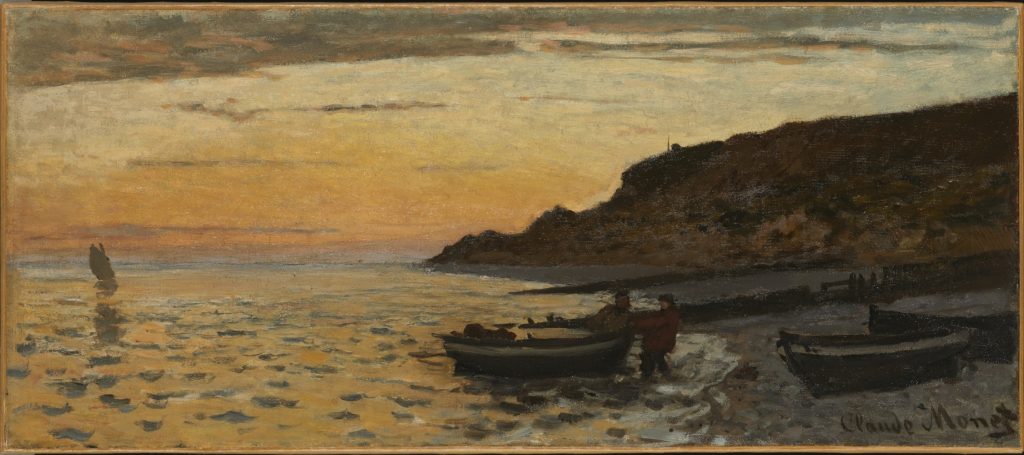

An 1864 view of the seaside in Le Havre, Normandy, where the two brothers grew up, is one of the most important early masterpieces by Claude from Léon’s collection.

Claude Monet, La plage à Sainte Adresse (1864). Photo: © Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts.

Léon also bought this sensitive portrayal of Claude’s first wife, Camille Doncieux, in a state of meditative rest. A reference to the considerable influence of Japonisme on the artist’s works can be found in the fan resting on the mantlepiece, showing a floral design that carries on to the other fabrics in the room. “I think Léon was interested in this painting because of that pattern,” speculated Lefebvre.

Léon presented the work at a local exhibition in Rouen in 1872, proudly putting his name in the catalogue to introduce himself as a collector.

Claude Monet, Méditation, Madame Monet au canapé (vers 1871). Photo: © Rmn – Grand Palais / Gérard Blot.

A year later, in 1875, Léon attended an auction of Impressionist works where he bought the first lot, his brother’s painting of the river Seine. He also encountered some of Claude’s peers, including Sisley and Renoir, whose painting of Paris below he also acquired at the sale.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir,

Paris, l’Institut au Quai Malaquais (1872). Photo: © Courtesy of the painting’s owner.

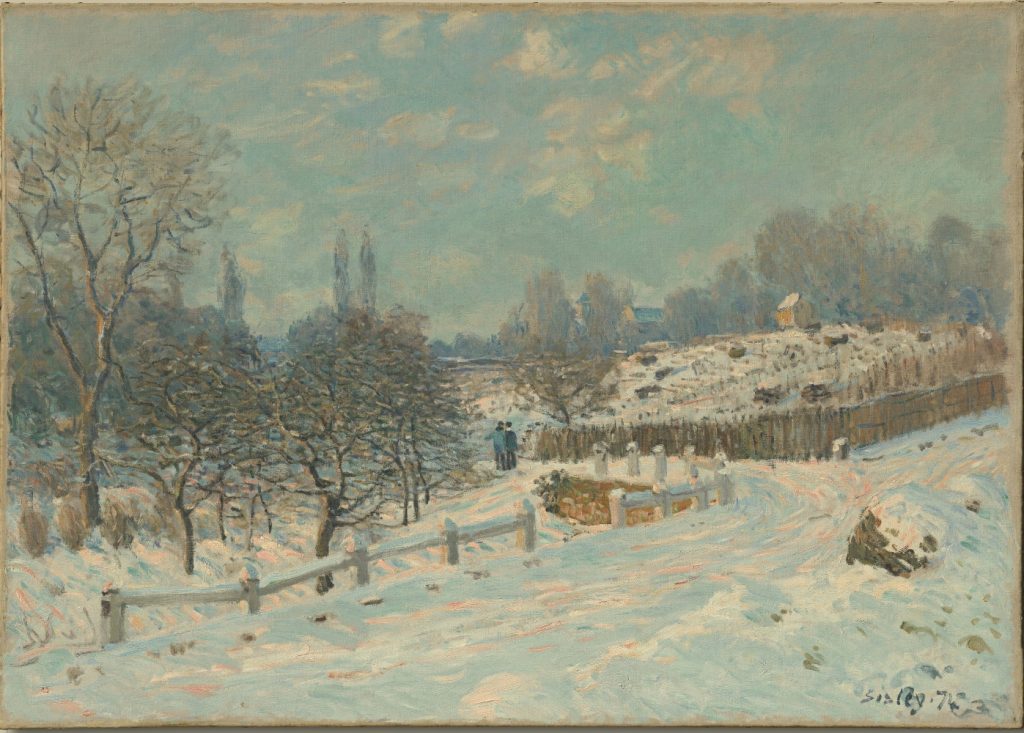

Léon also bought a wintry snowscape by Sisley according to old photographs of his collections. Though the specific work is in a private collection, it would have looked similar to the painting below, which is included in the exhibition.

Alfred Sisley, Route de Louveciennes, effet de neige (1874). Photo: © Hasso Plattner Collection.

When Pissarro visited Rouen for the first time in 1883, he stopped by Léon’s house for dinner. The men had been friends since 1872 thank to the connection made by Claude, and Léon became an early collector of Pissarro’s. “It was important for an artist to go to places where they know they can find a collector who will buy their paintings,” explained Lefebvre.

During the visit, Pissarro became inspired by his new surroundings and dashed of the below sketch of the town and its surrounding hills. Léon immediately snapped up both this and another depiction of Rouen the very same day they were painted.

Camille Pissarro, Environs de Rouen (1883). Photo: © Courtesy of Sotheby’s, Inc.

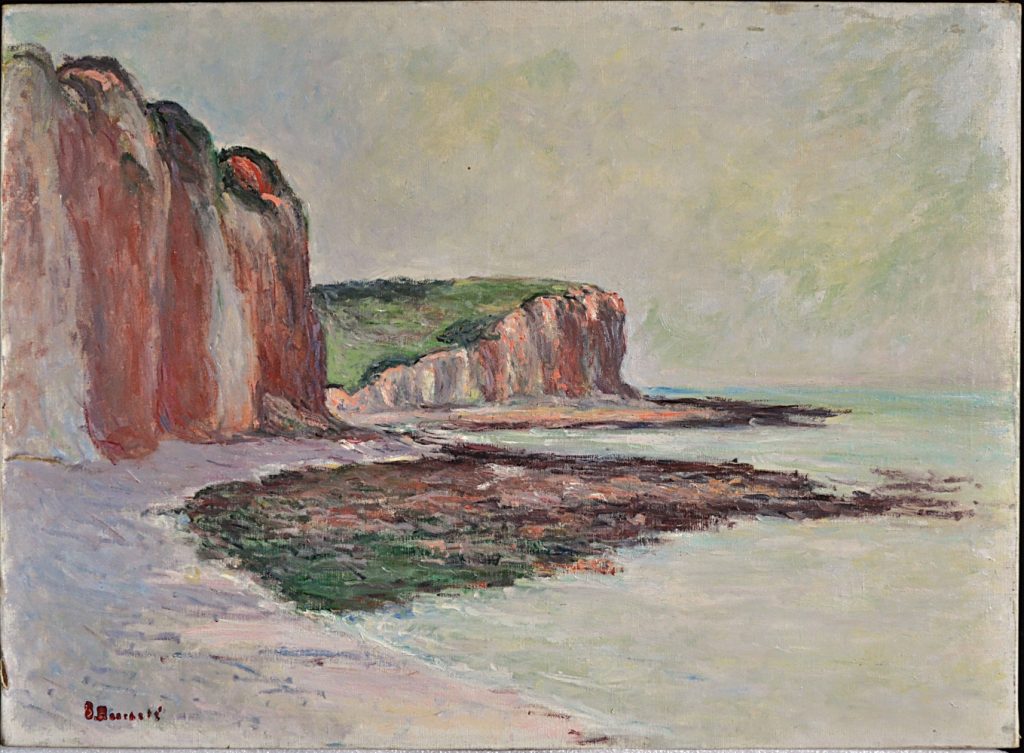

Léon also bought a work of the beach at Les Petits-Dalles in Normany by Claude’s step-daughter Blanche Hoschedé Monet, the daughter of his second wife Alice who followed in his footsteps to become an Impressionist painter.

Blanche Hoschedé Monet, Les Petites-Dalles (1885-1890). Photo courtesy of Musée du Luxembourg.

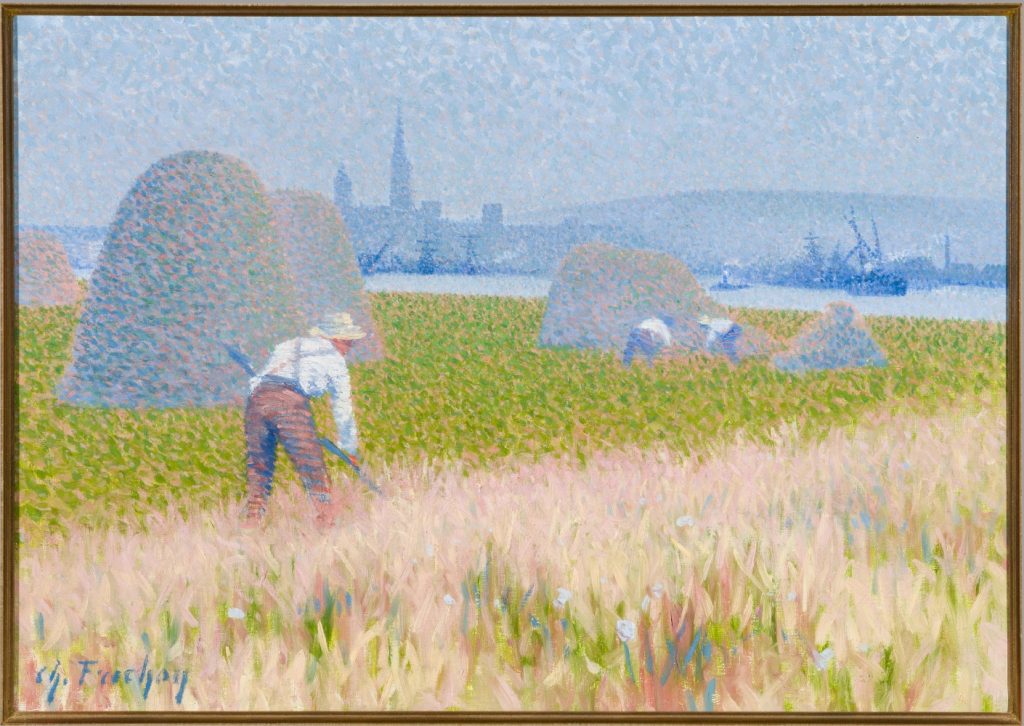

Finally, Léon was also interested in works by the lesser-known painter Charles Frechon, a native of Rouen who also notably worked as a draughtsman for the dye industry. “To earn a living these artists made patterns for fabric manufacturers,” explained Lefebvre.

The painting below is not the same autumnal sketch that the collector is known to have acquired, but it spotlights the unique style of the artist.

Charles Frechon, Fenaison, Rouen depuis la rive gauche (1891-1895).

More Trending Stories: