Museums & Institutions

Not Patriarchal Art History, But Art ‘Herstory’: Judy Chicago on Why She Devoted Her New Show to 80 Women Artists Who Inspired Her

"It's about rewriting history," curator Massimiliano Gioni said.

"It's about rewriting history," curator Massimiliano Gioni said.

Sarah Cascone

Judy Chicago is famous for The Dinner Party (1974–79), a work of art celebrating the overlooked historic achievements of women. So, it’s fitting that the great feminist artist’s first New York survey, “Judy Chicago: Herstory,” opening at the New Museum in October, will pay homage to women throughout history.

The exhibition-within-the-exhibition titled “The City of Ladies” will feature work by more than 80 women artists, writers, and cultural figures. Some are art history’s most famous women, such as Frida Kahlo, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Artemisia Gentileschi, as well as the likes of Paula Modersohn-Becker, Elizabeth Catlett, and Käthe Kollwitz. There are also women from other fields, including Gertrude Stein, Virginia Woolf, Emily Dickinson, Martha Graham, and Emma Goldman.

The works will be displayed alongside several of Chicago’s major pieces, with monumental banners from her series “The Female Divine” (2022), created for a Paris fashion show with Dior, hanging overhead. It’s an unusual curatorial choice, but one that makes perfect sense when viewed through the lens of Chicago’s oeuvre.

For decades, she has made an art of collaboration, enlisting women with unique artistic skills to help realize her visions for ambitious projects like The Dinner Party and “The Birth Project” (1980–85). And if one half of Chicago’s practice is her physical work, the other is her deeply researched archival studies, uncovering the histories of women and their mastery of art forms wrongfully relegated to the realm of craft.

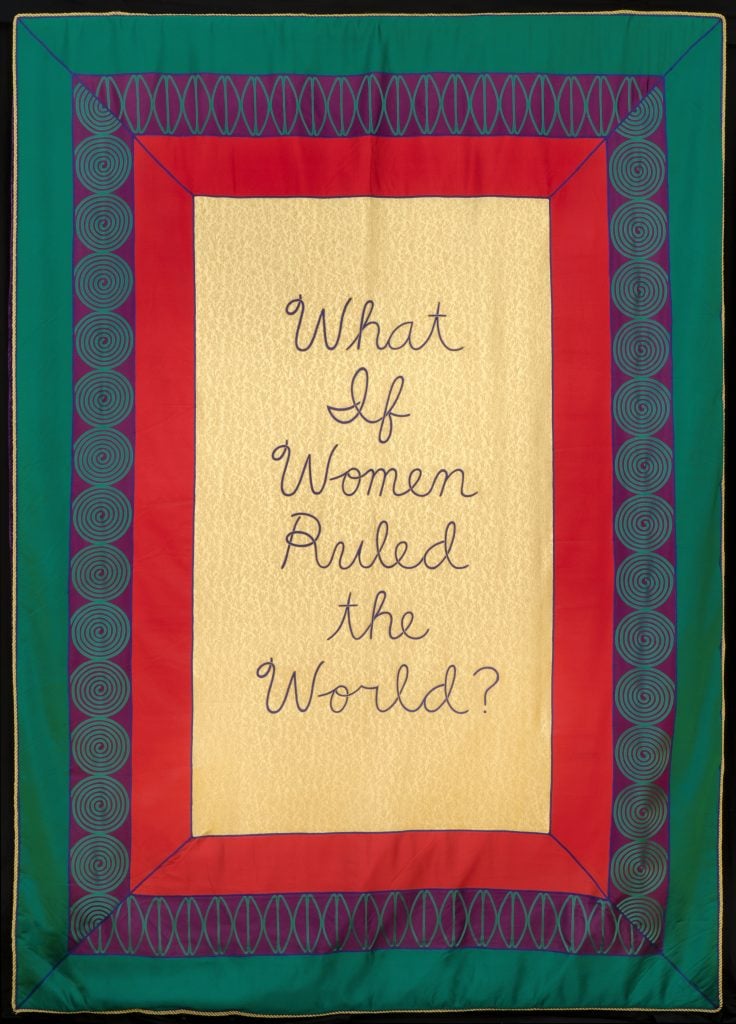

Judy Chicago, What if Women Ruled the World? from “The Female Divine” (2020). ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS). Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation.

“If there is Judy, there is also women’s history. If there is Judy, there are also other women,” New Museum artistic director Massimiliano Gioni, who curated the show with Gary Carrion-Murayari, Margot Norton, and Madeline Weisburg, told Artnet News. “And so that’s how we came to this.”

One of the place settings in The Dinner Party is dedicated to Christine de Pisan, the author of the 15th-century protofeminist book Le Livre de la Cite des Dames (or The Book of the City of Ladies), which lends its name to the section in Chicago’s upcoming show.

“Christine [de Pisan] was the first woman in Europe to ever support herself by writing. She was widowed at 25 with three children, and she took up her pen to write. And she wrote that book in response to a very popular and very misogynist book called Roman de la Rose,” Chicago told Artnet News.

“In the book, Christine describes sitting at her desk and thinking, ‘maybe women really are inferior,’ whereupon three figures appear before her: Reason, Justice, and Virtue,” Chicago continued. “And they say, ‘Don’t be foolish, Christine. What you have to do is… counter this idea by building creating a City of Ladies’—which she did.”

Gluck (Hannah Gluckstein), Portrait of Miss E.M. Craig (1920). ©Estate of Gluck (Hannah Gluckstein). Courtesy Piano Nobile, London

When the artist, who is 83, first learned about the book during her work on The Dinner Party, it wasn’t even translated into English. But Chicago sees City of Ladies as evidence that the roots of feminism go back centuries earlier than is generally acknowledged, and that there is an unknown cultural history written by women.

“One of the things I discovered in the ’70s,” Chicago said, “was this incredible hunger among women for images that affirmed them.”

At the New Museum, Chicago and Gioni are building their own “City of Ladies” on the fourth floor as a way of illuminating centuries of women’s creativity and showing how Chicago’s own work stems from this unacknowledged history.

“I hope it will transform the way people see my life, [and] that they will begin to understand my work in a different history than patriarchal art history,” Chicago said. “There is an alternative canon that already exists, [and] doesn’t have to be created. It’s just been excluded.”

Mary Louise McLaughlin, “Ali Baba” Vase (1880). Collection of the Cincinnati Art Museum. Gift of the Estate of Jane Gates Todd 2018.

“Massimilliano is making visible the multiple historic contexts out of which my six-decade career grows,” she added, noting that people have had difficulty understanding her work because they are ignorant about topics like women’s needlework and ceramics. “I did not actually understand that this was the reason for the complete lack of comprehension of my work for so long.”

The artist and the curator first met while working on “The Great Mother,” an exhibition on depictions of motherhood in 20th- and 21st-century that Gioni curated for Expo Milan in 2015. Chicago had started “The Birth Project,” featured prominently in the show, to correct what she was as the absence of maternal imagery in historical artworks.

“What Massimiliano’s show taught me is that erasure is not just the erasure of individual women’s achievements. Erasure also applies to subject matter that the patriarchal art world considers unimportant, like birth and motherhood—because it turns out there is a huge body of art on those subjects dating back to the beginning of the 20th century,” Chicago said. “Dada, Futurism—I was completely blown away.”

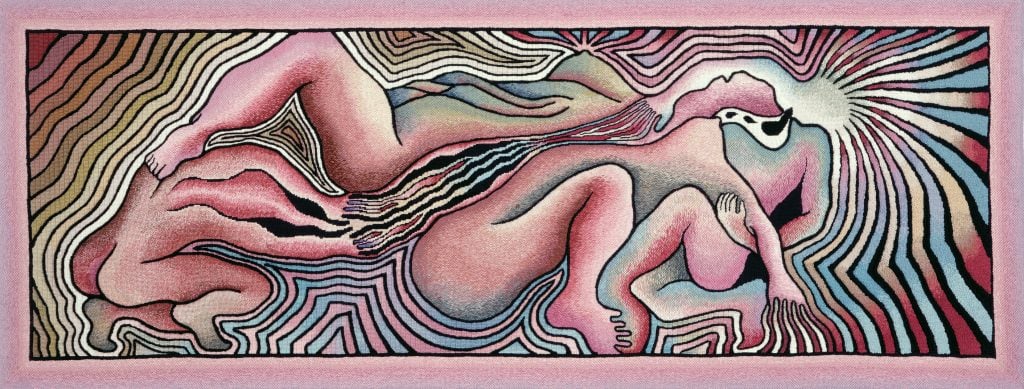

Judy Chicago, Birth Trinity: Needlepoint 1 from “The Birth Project” (1983). Needlepoint by Susan Bloomenstein, Elizabeth Colten, Karen Fogel, Helene Hirmes, Bernice Levitt, Linda Rothenberg, and Miriam Vogelman. ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. The Gusford Collection. Photo by Donald Woodman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Some of the women in “The City of Ladies” have inspired Chicago for years. Others, even the artist—obviously an enthusiastic student of women’s history for decades—had not known before Gioni began putting together the show.

“It’s gonna be a huge learning experience for most viewers,” Chicago said.

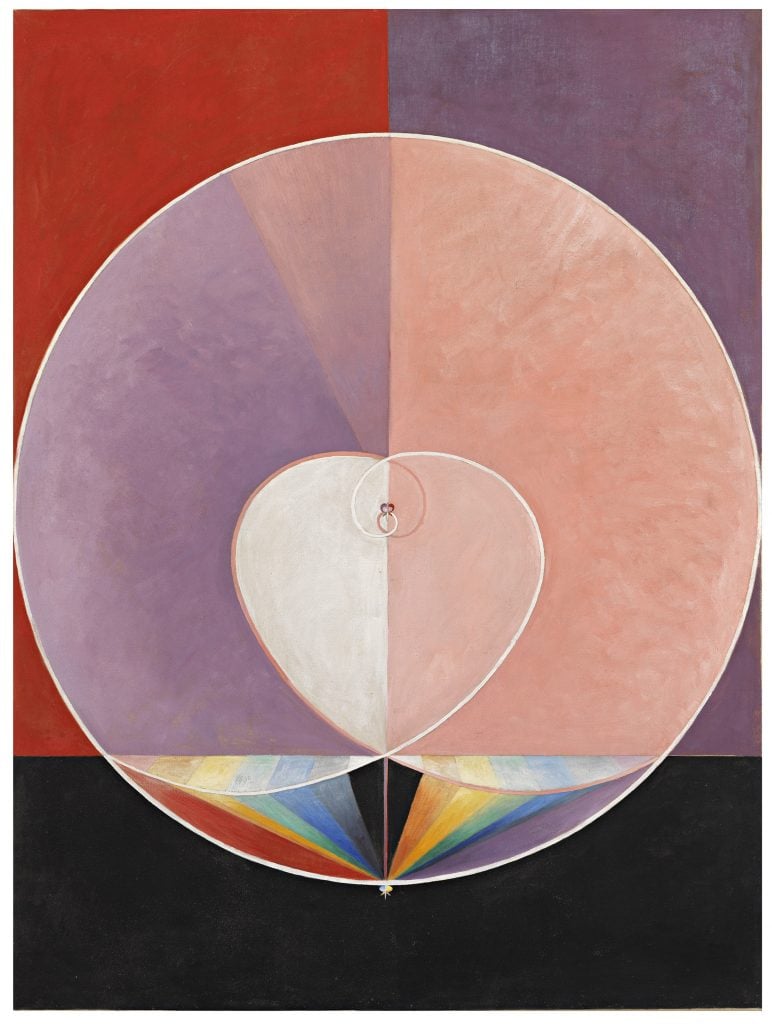

But even if she didn’t encounter Hilma af Klint’s pioneering Spiritualist abstractions until the artist’s blockbuster show at New York’s Guggenheim Museum in 2018, Chicago sees a through line between her work and that of the late Swedish artist. “The City of Ladies,” Chicago believes, will demonstrate that women have always been working in their own art historical traditions, separate and distinct from that of men.

Hilma af Klint, Group IX/UW, The dove, no.2 (1915). ©The Hilma af Klint Foundation.

“Mainstream institutions have been trying to figure out how to add women and artists of color around the perimeter without challenging the patriarchal paradigm,” Chicago said. “But I’ve been working entirely in a different paradigm.”

The showcase won’t just include art. There will be a copy, for instance, of 19th-century French animal painter Rosa Bonheur’s official application to be granted permission to wear men’s clothing in public.

There will also be a focus on what Chicago has termed central core imagery, in which an artwork is built from the center radiating out, rather than from the edges of the canvas moving in.

“In the ’70s, I studied the work of many women artists and discovered that, like me, there were many women who constructed their images from the center,” Chicago said. “It reinforced my own impulses at a time when the craze was to create compositions from the edge, which I always felt alienated from.”

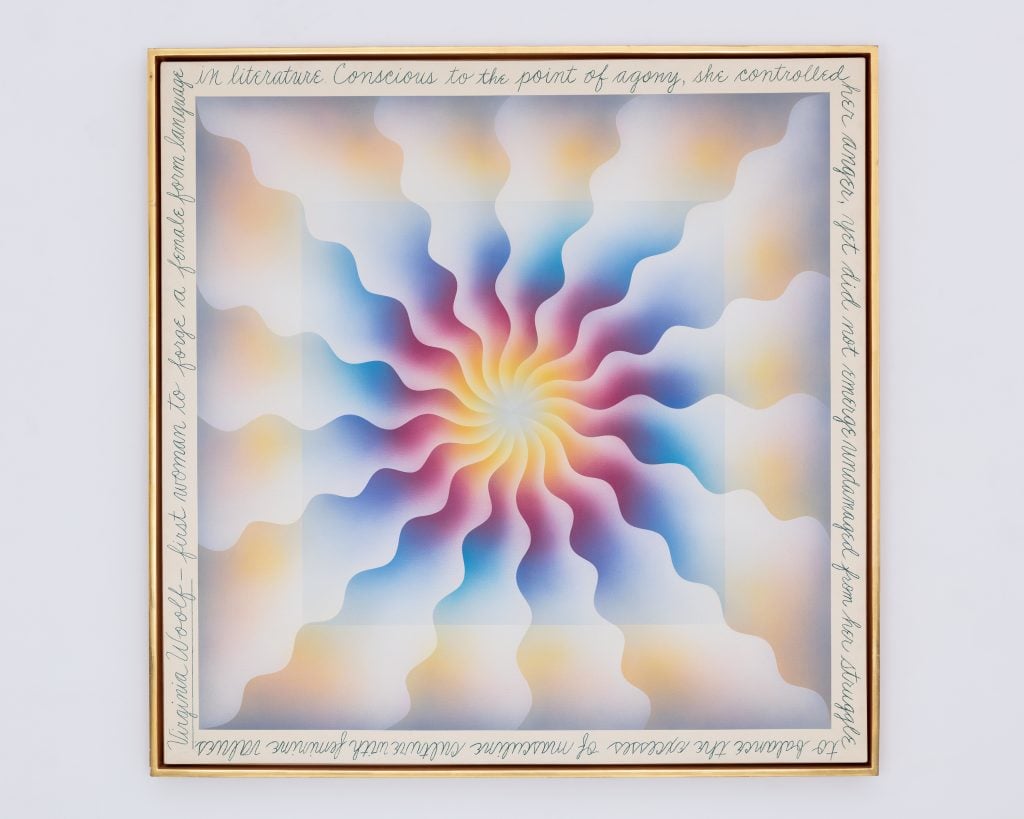

Judy Chicago, Virginia Woolf from “The Reincarnation Triptych” (1973). ©Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Collection of Kirsten Grimstad and Diana Gould.

Her writings on the subject were ridiculed at the time, Chicago added, but “could have opened up a whole stream of understanding of work by women based in a different body impulse because we exist around the central core.”

Bringing together the loans for “The City of Ladies” was a bit outside the wheelhouse for the New Museum, which is dedicated to contemporary art. “It is probably the only time we will have Hildegard of Bingen and Artemisia Gentileschi,” Gioni said.

But the exhibition is an important step toward improving an understanding of women in art history—and neither the Museum of Modern Art nor the Metropolitan Museum are taking that on.

“Why is it still the alternative museum that has to do it? it’s amazing that we’re doing it, but we’re still the alternative museum,” he said. Nevertheless, somebody has to be doing this important work: “It’s about rewriting history.”

“Judy Chicago: Herstory” will be on view at the New Museum, 235 Bowery, New York, New York, October 12, 2023–January 14, 2024.