Art World

High-Tech Radar May Have Just Led Researchers to Discover Nefertiti’s Secret Burial Chamber in King Tut’s Tomb

If true, “it could be the biggest archaeological discovery ever."

If true, “it could be the biggest archaeological discovery ever."

Taylor Dafoe

Researchers may have discovered a hidden chamber in the tomb of Tutankhamun, reigniting a centuries-old theory about the true final resting place of Egyptian queen Nefertiti.

A team of archaeologists, led by former Egyptian minister of antiquities Mamdouh Eldamaty, turned to ground-penetrating radar technology to analyze the area surrounding Tutankhamun’s 3,400-year-old tomb in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. They detected evidence of an unknown corridor meters away from the Pharaoh’s burial chamber that led to a 32-foot-wide chamber.

The scientists’ findings were presented to Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities earlier this month and collected in an unpublished report obtained by the journal Nature, which first reported the story.

The finding immediately stoked speculation that this chamber could be the tomb of Queen Nefertiti, a female pharaoh who many believe ruled Egypt for a short period during Egypt’s 18th Dynasty in 1300 BC. The prevailing belief among Egyptologists today is that the queen was Tutankhamun’s mother in law. Despite her outsized presence in Egyptian history, her burial place was never found.

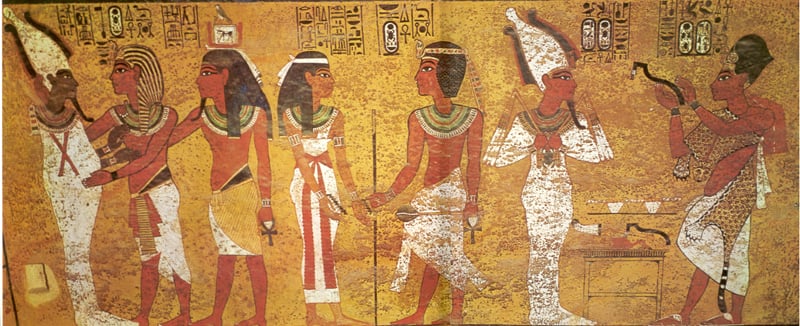

Archaeologist Nicholas Reeves believes this painting in King Tut’s tomb marked the closing of Nefertiti’s now-hidden burial chamber. Courtesy of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The discovery made by Eldamaty’s team is the latest development in an ongoing debate waged by experts over the existence of a secret chamber connected to King Tut’s tomb.

In 2015, British archaeologist Nicholas Reeves claimed that, through high-resolution surface scans, he found evidence of hidden doorways behind the painted walls of Tut’s burial chamber. Later that year, in a survey overseen by Eldamaty, the Japanese radar specialist Hirokatsu Watanabe corroborated Reeves’s theory with evidence of his own. However, further radar scans of the area in question—including one conducted by National Geographic, which was also supervised by Eldamaty—proved to be inconclusive at best, leaving many in the field doubtful.

Egypt’s Minister of Antiquities, Mamdouh al-Damati listens to British Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves near the sarcophagus of King Tutankhamun in his burial chamber in the Valley of the Kings on September 28, 2015. Photo: Khaled Desouki/AFP via Getty Images.

In 2017, the year after Eldamaty left his post as antiquities minister, the state ordered two new surveys of Tut’s tomb. The first, led by Italian physicist Francesco Porcelli inside the tomb, found no evidence of a hidden room. The second, conducted by UK geophysical survey company Terravision Exploration, did, but the study was halted by Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities before its completion.

Eldamaty, currently based at Ain Shams University in Cairo, returned with Terravision last year to facilitate the company as it finished its work. Eldamaty now plans to apply to study the area again in more detail.

“If Nefertiti was buried as a pharaoh, it could be the biggest archaeological discovery ever,” Reeves told Nature.