Art World

Iran Was on the Hunt for a Stolen Persian Book Worth $1.1 Million. But the ‘Indiana Jones’ of the Art World Beat Them to It

The 14th-century manuscript was missing since 2007.

The 14th-century manuscript was missing since 2007.

Sarah Cascone

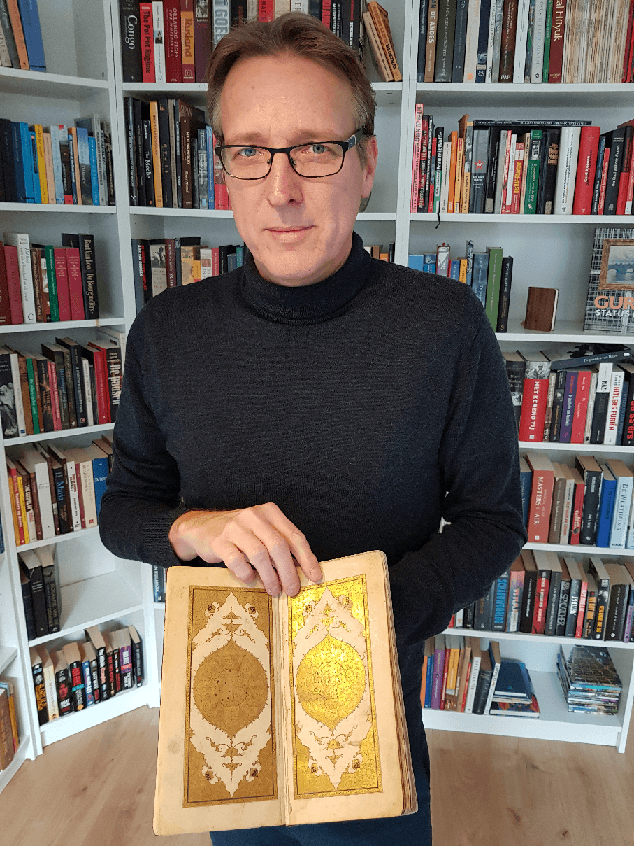

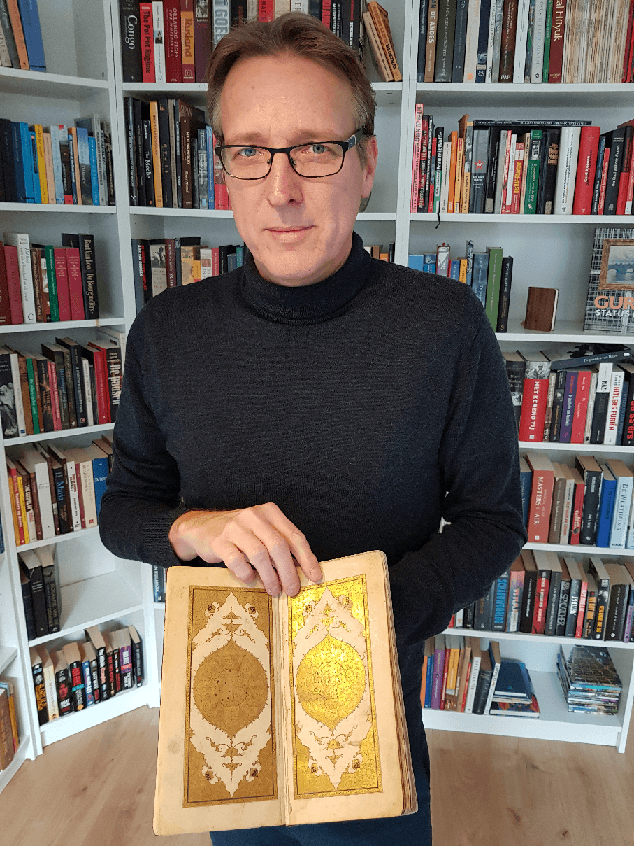

Dutch art detective Arthur Brand, lauded as the Indiana Jones of the art world, has solved another major case, recovering an ancient manuscript known as the Diwan of Hafez.

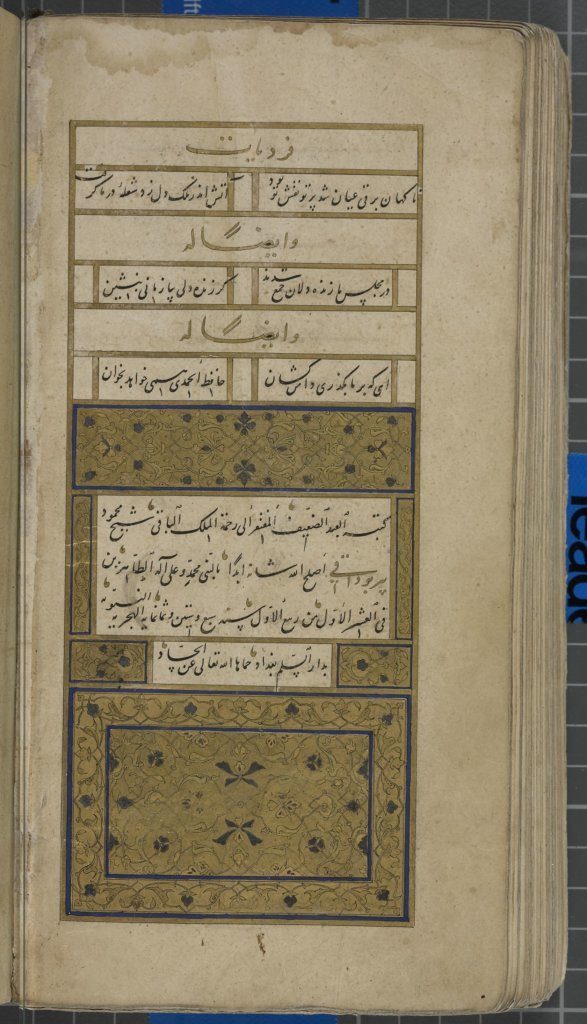

Featuring the collected works (or diwan) of the 14th-century Persian lyrical poet Hafez, the handwritten and gold leaf-embellished book was stolen in 2007 and is worth €1 million ($1.1 million), according to German authorities.

Despite Brand’s extensive experience in the field, locating it was particularly challenging because of the Iranian government agents who were also hot on its trail.

“We understood that the Iranian government was after it. It was a race between them and me—but luckily they didn’t know I was after the book,” Brand tells Artnet News. He took on the case in late 2018, when an Iranian contact in Germany was approached by men he believed were Iranian secret service agents, asking questions about the stolen manuscript.

Before it was stolen, this Diwan of Hafez belonged to Djafar Ghazy, an Iranian collector who lived in Munich. When he died in 2007, at the age of 86, he left behind a valuable collection of ancient Islamic and Persian manuscripts, but Ghazy’s relatives soon realized they had all been stolen.

The police were able to crack the case and arrest the thief in 2011, recovering a cache of 175 books and manuscripts—but not the Diwan of Hafez, the most important of the lot.

“They call Hafez the Shakespeare of Persian literature,” Brand says. “He’s incredibly important for hundreds of millions of people in the Arab world. There’s a joke: people in Iran only have two books, the Diwan of Hafez, and the Koran, and they only read one of them.”

This particular copy of his collected works dates to about 1462 or 1463, and Hafez died around 1389, making it one of the oldest—and therefore most accurate—copies of the text.

The Diwan of Hafez. Photo courtesy of Arthur Brand.

“That makes it so important,” Brand says. “Hafez only had an oral tradition, he didn’t write anything down. The handwritten books that appeared soon after his death are the most reliable.”

In his will, Ghazy donated two books to the Iranian government, which subsequently demanded the repatriation of the entire collection—a demand dismissed by the German courts.

Brand only only learned of the theft when Iranian agents turned up in Germany asking questions about the still-missing Diwan of Hafez. “It seems that the Iranians thought, ‘Let’s try to find that one, and if we find it, we’ll take it back.'” says Brand, who during his year-long search spoke to several contacts who were approached by the Iranians. “You could see in their eyes that they were pretty scared.”

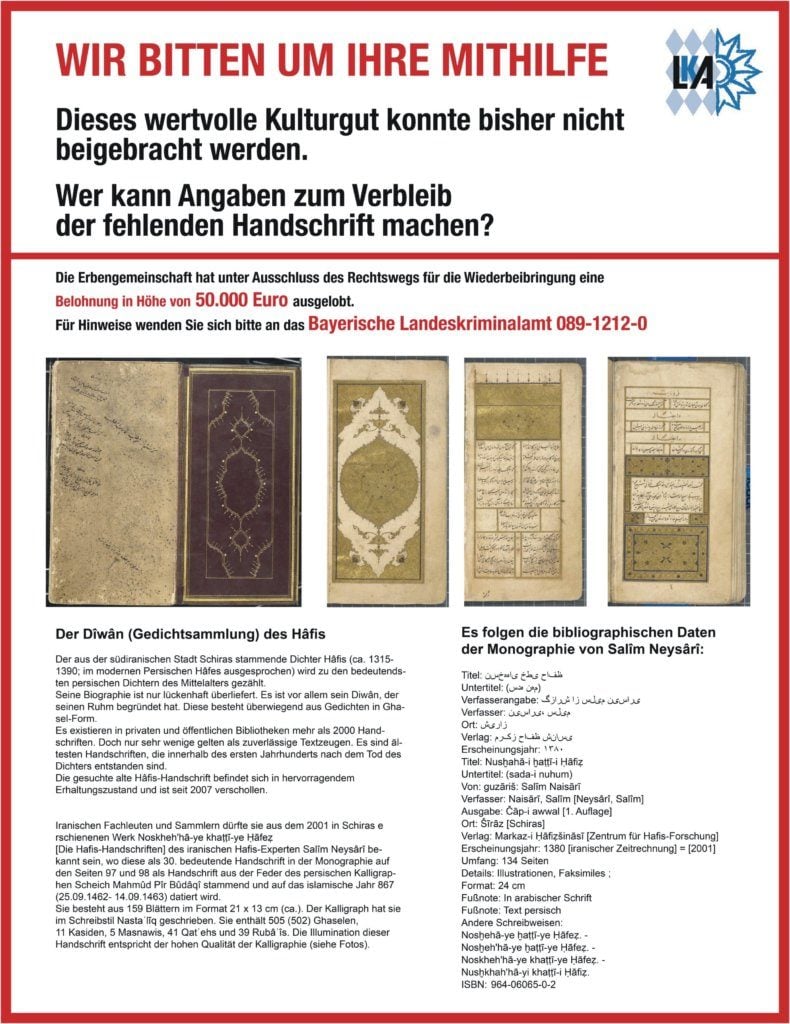

The German government put out a wanted poster for the Diwan of Hafez with a reward.

After putting out the word to various contacts, Brand’s search led him to England, where William Veres, an antiquities dealer, put him in touch with someone who eventually admitted to having seen the book. The man first demanded proof that the Diwan of Hafez was stolen, and Brand produced a wanted poster and a news article, both in German. The man then admitted that a deceased colleague had sold it to an important Iranian collector in London.

“We said, ‘Go and tell him the book is stolen and the Iranians are after it, so he better talk to us,'” Brand recalls. “The owner was flabbergasted. He was shocked that he had a stolen book in his possession, he was shocked that the Iranians were asking around, and he was shocked that I was after him.”

Luckily, Brand was able to convince the collector to give up the book.

“Stolen art does wind up in the hands of people who are completely innocent—especially with small, lesser-known works,” Brand says. “We once discovered a stolen icon on the wall of the English singer Boy George, and he had no idea.”