Artists

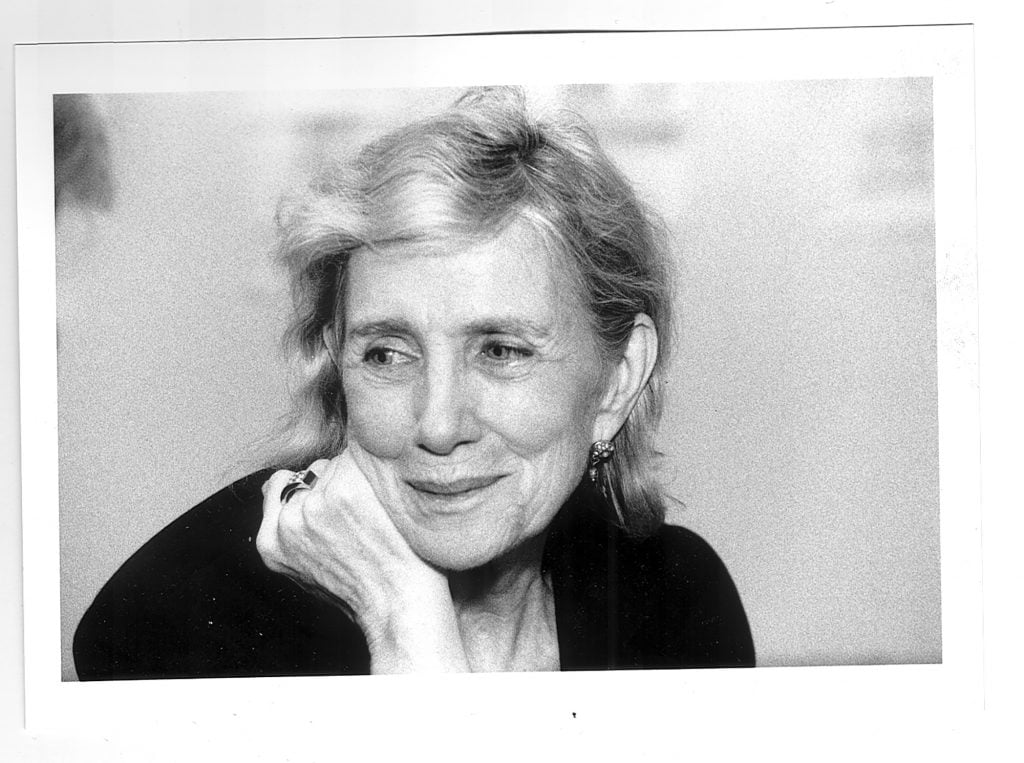

‘Somehow You Do the Impossible’: At 95, Dorothea Rockburne Reflects on Her Polymathic Career

The 95-year-old artist's first U.K. survey "The Light Shines in the Darkness and the Darkness Has Not Understood It" is now on view at London's Bernheim Gallery.

At 95 years old, Dorothea Rockburne is still giving form to the geometries of the universe. The abstract artist who, over the decades steadily earned acclaim for her drawings, installations, and sculptures that articulated mathematics of set theory, topology, astronomy, and phenomenology, greeted me at her Soho loft where has lived and worked for over 50 years, on a day this past August.

In the open, surprisingly quiet space, Rockburne was accompanied by her kitten, Mickey Mouse, who was still less than a year old. Her assistant, Will, popped in and out of the apartment. Rockburne, who was born in Montreal in 1929, is regarded as one of the defining New York artists of the second half of the 20th century, and her loft, while still an active studio, is also an archive of life’s interests, shelves and tables covered with ranging books on Giotto to recent mathematics periodicals.

Rockburne moved into the loft with her daughter in 1972, when they were evicted from a studio and apartment on Chambers Street. “Somebody told me about this place. It seemed quite challenging because it’s so big, but I didn’t have time to look for something,” she recalled, “But it has a ton of light and it’s been a terrific space.”

Here, over the decades, Rockburne pushed her ever-evolving, polymathic approach to art-making, incorporating unlikely materials from plain paper and vellum to crude oil, grease, and tar.

Right now, over two dozen works by Rockburne, many made in this very studio, are on view in “The Light Shines in the Darkness and the Darkness Has Not Understood It” an exhibition curated by Lola Kramer, at Bernheim Gallery in London (on view until January 25). The exhibition marks Rockburne’s first European survey and includes work from 1967 to 2013, many of which are being shown outside the U.S. for the first time. Later this month in Paris, Ceysson & Bénétière Gallery will open an exhibition showcasing three major series by Rockburne—Trefoils, Blue Collages, and Reflections—underscoring the breadth of her artistic experimentation (January 29-March 15).

Tracing the arc and evolution of Rockburne’s career, the Bernheim Gallery show includes seminal early experiments with wrinkle-finish paint to her defining folded works in vellum and linen along with her topology-based geometric paintings The exhibition title is a translation of the Latin phrase “Lux in tenebris cet et tenebrae eam non comprehenderunt,” which appears in the Gospel of John. The quotation is one Rockburne translated and referenced with some frequency in the late 80s. It speaks, poetically, to Rockburne’s interests in seemingly diametrical fields: shadow and light, structure and plane, color and transparency.

Rockburne is, in many senses, a quintessential New York artist. After graduating from Black Mountain College in the early 1950s, Rockburne, like her classmates and friends Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly, made her way to New York, where she integrated herself into the art world. The earliest work in the exhibition is Tropical Tan which dates to 1967–68, a period when Rockburne’s career was rising. Also included is her influential Domain of the Variable (1972), a work in the collection of Dia, which appeared on the cover of Artforum in March 1972. Other highlights include her Golden Section Paintings (1974-76) and Egyptian Paintings (1979-80), which were prominently included in Rockburne’s 2018 survey at Dia Beacon. “New York is always changing, always growing,” she shared. “There’s always some individual or group that crack it and change it all over again, turn it into something else, and it’s fascinating to watch over the years.”

The London exhibition offers a cogent introduction to Rockburne’s remarkably multifaceted output over the decades, drawing out through-line engagements with mathematics, the cosmos, and spatial relations. For Rockburne, the exhibition offered a moment to consider the decades of her life and work as she made her way as a single mother and an artist in New York. “Work like hell and believe” is her credo to younger artists.

Below, she shared more of her memories and artistic insights in an informal conversation.

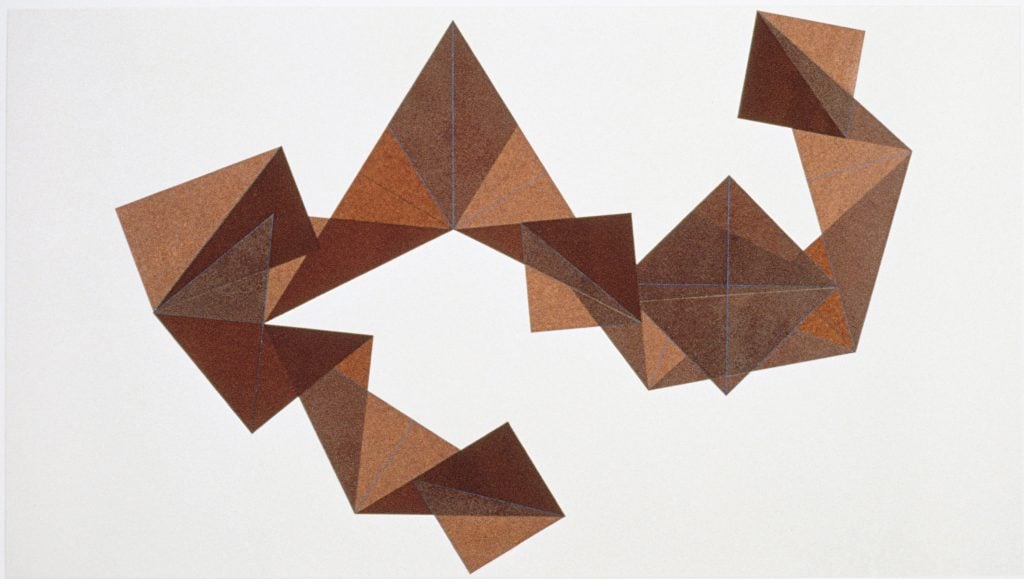

Dorothea Rockburne’s Domain of the Variable (1972) at Dia:Beacon. Courtesy of the Dia Art Foundation.

Your exhibition at Bernheim Gallery is a revisiting of works dating back to the 1960s to to 2013. Over the decades you’ve worked with many mediums, from vellum to grease and kraft paper. What is the thread that connects your works across the decades? Have you have you found answers or just more questions in your practice?

Neither questions nor answers. My work is a statement. What the statement is, is the work itself. It’s not a verbal statement.

Let’s go back to the beginning. You attended Black Mountain College in the 1950s. You were friends and classmates with Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly. How did you wind up there?

This was 1950. Back then if you went to college you went in as Dorothy Rockburne and you came out as what? A dietician? What I wanted was an education. I didn’t want a profession. I looked around everywhere and someone suggested Black Mountain. I sent for their information, and they seemed to fit the bill.

It was at Black Mountain College that you found your passion for mathematics, isn’t that right?

I stumbled into a math class. I liked the teacher, whose name was Max Dehn, a lot and he took me under his wing. I slowly became a mathematician. A lot of it was self-directed but he was a very good teacher. We stayed in touch after I graduated. Finally, I got a doctorate in mathematics from Bowdoin in 2016.

Dorothea Rockburne, Domaine of the Variable (Y), (Z) (1972). Courtesy of the artist and Bernheim Gallery.

What appealed to you about math? What did mathematics offer you as an artist?

I’m very interested in natural phenomena. I am trying to think, as all artists are, of how the sun moves, how trees grow. All of that has a mathematical principle. I try to shine the light on various aspects of those principles to make it more clear.

You were born in Montreal in 1929. Even before attending Black Mountain, you took art classes.

That was a more traditional education. It stayed in my work. For instance, I never mixed colors. If I want to make a purple, it’s all glaze. That sort of thing.

What were your parents like?

My father was a sweet father. My mother was a product of her age. She was frustrated because she was very smart and could never work in her field, which was a dietician.

Did they encourage your ambitions?

They didn’t even think of children in that way in those days. It was different.

Do you have any early memories of art?

I remember when I was quite young, maybe 6 or 7 years old looking at Picasso. I don’t know why there was a Picasso book in our house. I remember thinking how wonderful it was and I remember showing the book to my mother. My mother thought it was awful. And that I thought: What? Why? Why is that offensive to her? It was really kind of funny to me.

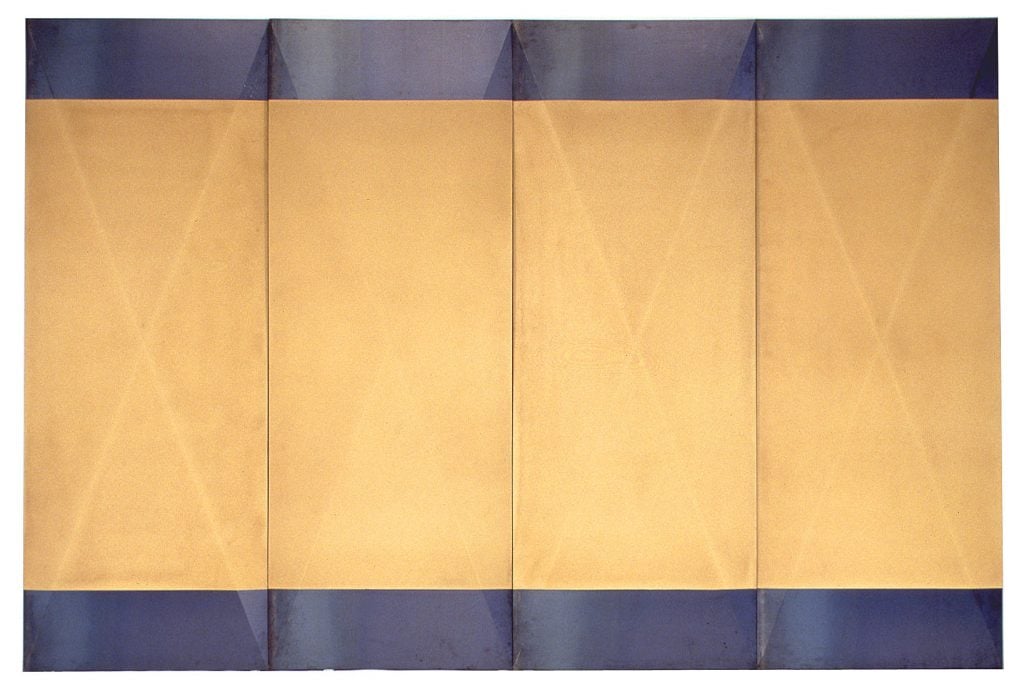

Dorothea Rockburne, Copal VIII (1979). Courtesy of the artist and Bernheim Gallery.

After leaving Black Mountain College you came to New York. Tell me about that time.

I was married at Black Mountain and my daughter was born. I have a 72-year-old daughter. My husband, my daughter, and I came to New York. I was in New York because of the museums. I studied at the museums and worked at the Met for a while. I found my way around the art world by going to openings and meeting people. I was friends with other artists. I knew there was a very important dealer named Dick Bellamy, who later had a very important gallery on Chambers Street called Oil and Steel. He was around. In those days the art world was small. You just went to all the openings and you met people.

You and your husband separated and you raised your daughter alone. What was it like raising a daughter and trying to make it as an artist in that era?

I never thought about trying to make it as an artist. I thought I was an artist. But it was very tough. I lived on Chambers Street and my daughter had a scholarship to Dalton, which is on 89th Street. Every morning, I took her all the uptown on the subway to Dalton. Then I went to a job. Then I picked from Dalton around 4:30. Sometimes she had a play date. We went home and I did homework with her. I made dinner and ate with her. Then read to her. I read her the Greek myths. Then I’d lie down and go to sleep with her at around 9 o’clock. I’d wake up around 10 and I’d go into the studio and work until two or three in the morning.

I was the total support for my daughter and me. I received no child support for her. I don’t know how I did. It seems impossible, but somehow you do the impossible. And we had a lot of fun doing it.

Once I remember there was a flea circus in Times Square. You looked at it through a magnifying glass of these little fleas were running races. The little girl fleas had on little skirts. My daughter remembers this. I’ve told people this, they don’t believe it but it’s true!

We had ways of living so we didn’t spend much money. For instance, at a yard sale in Provincetown, I bought her a bicycle for 50 cents and then taught her to ride a bike.

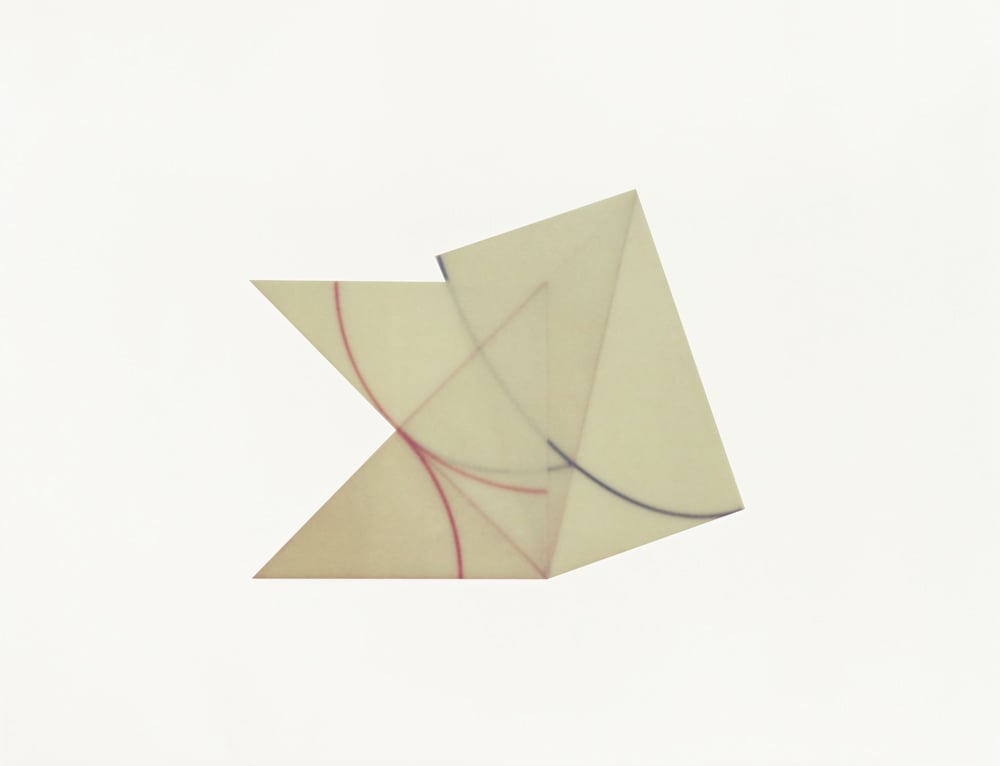

Dorothea Rockburne. Arena Study 2nd Version (1978). Courtesy of the artist and Bernheim Gallery.

In New York, you worked for Robert Rauschenberg, right?

I knew Bob at Black Mountain College. We were students together. When we were in New York, I worked for him. I don’t know what I did! I never worked on the artwork. I never wanted to do that.

Knowing and being close to Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly at such a young age at Black Mountain College… those are memories I treasure.

Was there anyone else you felt made a real impact on you in those years?

Oh, certainly Bob Ryman and Lucy Lippard. Lucy’s not in New York anymore, so I never see her. But Lucy was just a treasure. That was a time when women were not evolved. They didn’t talk up. They didn’t make their presence known, and Lucy did. So that was interesting to me. And I did, too, of course

What was Robert Ryman like?

He was always the same. He never talked. He was very, very smart. He dealt a lot in his work with nuance. How could nuance have its own voice, you know?

Your assistant, Will, is here today. He’s part of your apprenticeship which you’ve done for many years, where a young artist stays with you for two years. What inspired you to start these apprenticeships?

I’m classical in my approach to art. That’s the classical approach: you teach younger people and hopefully they’ll teach younger people. One of the people I taught for instance was Mel Kendrick. Mel is doing that still with people who are in his studio.

Dorothea Rockburne, Tropical Tan (1967). Courtesy of the artist and Bernheim Gallery.

You’re still in the studio making work at 95. What has given you the stamina? How did you manage to sustain your career over the decades?

There never seemed to be a choice. I think art, eat art, live art. That’s why I’m in New York. I want the museums. I want to know what other people are thinking and how they are transitioning from the original art object to what their art object is.

Is there any advice that was especially helpful to you in your career?

Bryce Marden’s dealer was Klaus Kertess, who was a very important dealer. And he used to call Bob Rauschenberg’s studio to talk to Bryce sometimes and I would talk to him as a transition. I got to know Klaus very well. Klaus was a very intelligent, very deep human being and very emotionally complex. Everybody in New York wanted Klaus Kertess to see their work.

We were always fooling on the phone and talking and so on and finally, he said, “What do you do?” I said, “Well, I’m making some drawings. He said he like to come and see them sometime and I said no. But eventually, I said yes. I lived at Chambers Street then and he came and looked at the drawings and he said something very important. He looked for like an hour before he said anything and he said “You need to take the core of what you’re doing and concentrate it into fewer works.” And so I did that.

What do you want the exhibition at Bernheim Gallery to say or express?

I want to present a very strong statement in materials, simple materials that give both mathematical and emotional information. I want to knock ’em dead.