Art & Exhibitions

Ed Hardy Is Hated for a Fashion Line He Had Little to Do With. A New Museum Show Is His Path to Redemption

Meet the artist behind the fashion brand.

Meet the artist behind the fashion brand.

Sarah Cascone

Before there was Ed Hardy the brand, widely reviled for its garishly colorful fashion designs sporting skulls, hearts, and flowers—to see how deep the hatred runs, just check Urban Dictionary—there was Ed Hardy the artist, a prolific tattoo master who helped make body ink mainstream.

Now, his life’s work is going on view in the artist’s first-ever museum retrospective, “Ed Hardy: Deeper Than Skin,” at San Francisco’s de Young Museum. The show, which opens in July, will bring together his custom tattoo designs, drawings, and paintings. It is a shot at redemption for an artist whose work has long been dismissed, minimized, and misunderstood.

“It’s an enormous validation for me,” Hardy told artnet News. “My entire life has been art. The only thing I was ever good at was drawing.”

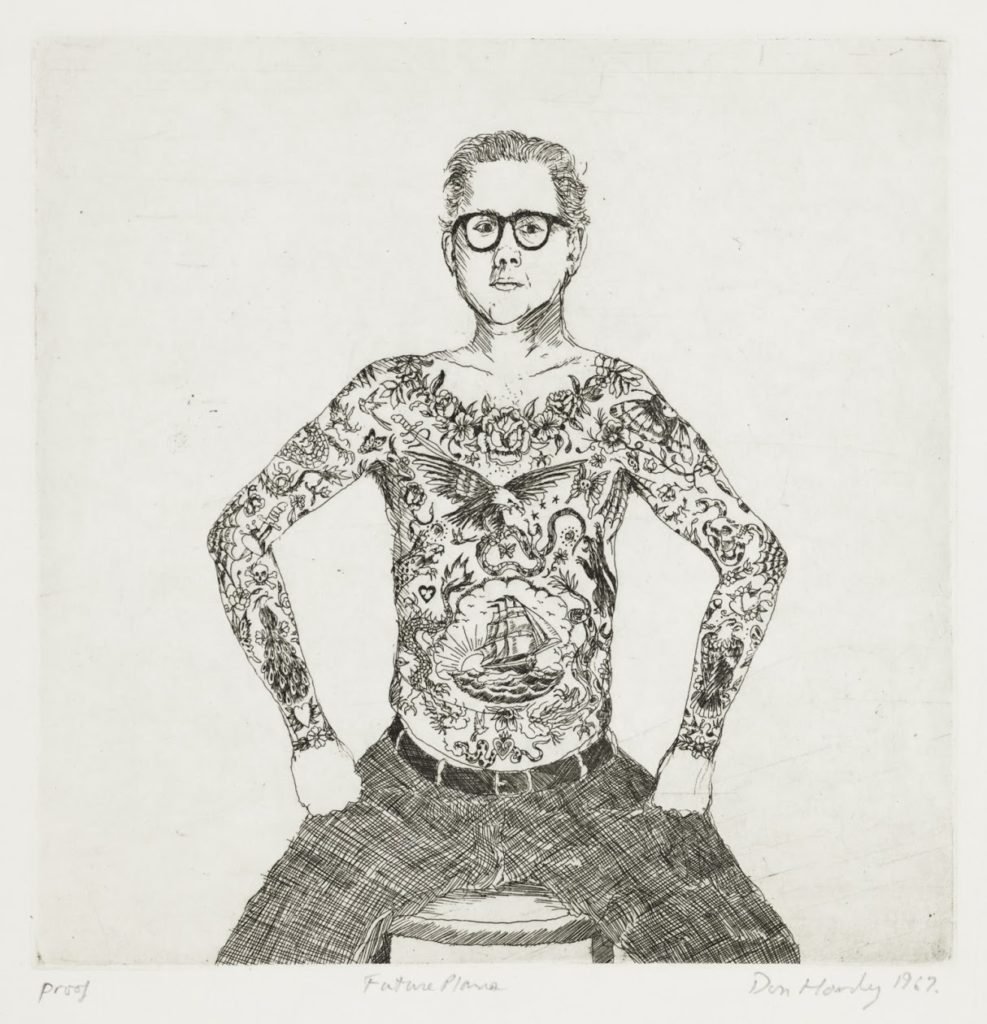

Born in 1945, Hardy got a BFA in printmaking from the San Francisco Art Institute. But when he turned to tattooing, he could never have known his work would one day be on view at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the very institution where he first encountered Old Master prints as a student. (He recently donated 150 of his own prints to the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts at the Legion of Honor.)

“In the days that I was first tattooing, people would see that you had tattoos and they would say, ‘Were you in jail or were you in the military?'” he recalled. “They couldn’t conceive of somebody just getting a tattoo. It was like the dark ages.”

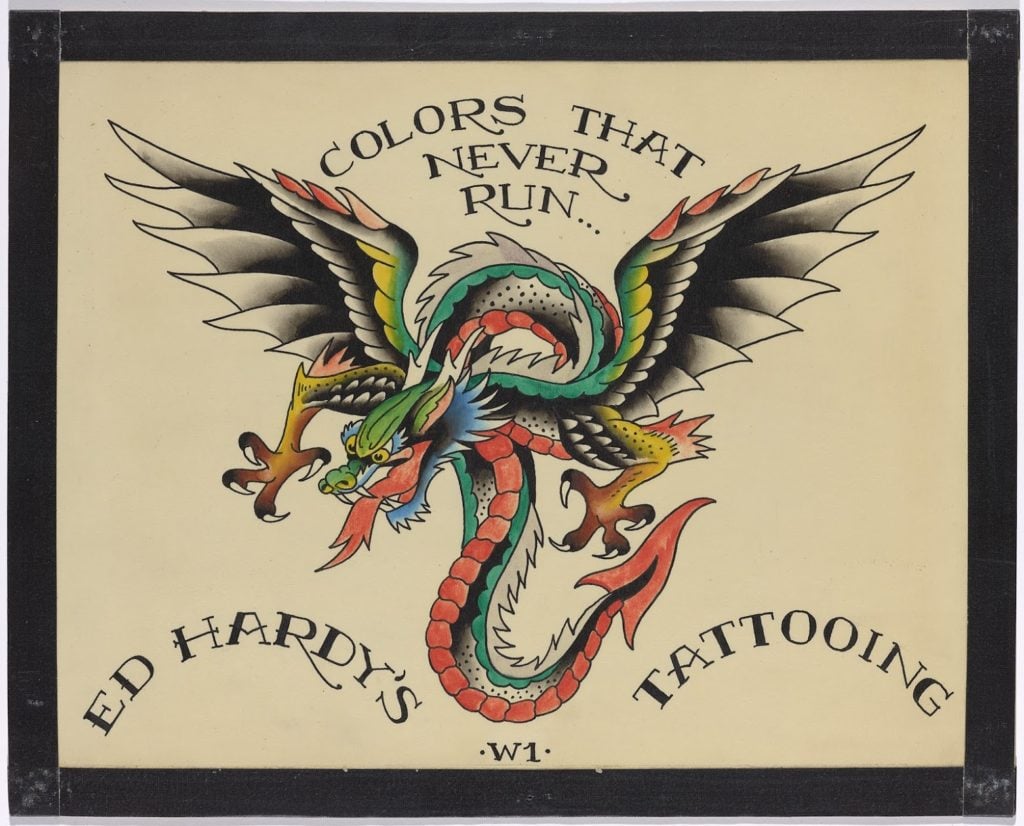

Don Ed Hardy, Colors That Never Run. Courtesy of Ed Hardy/Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

But to the young Hardy, the medium was endlessly fascinating. “I just felt that tattooing had so much potential as a form of human expression that had been totally demonized and looked down on,” he said.

Art school-trained and firm in his conviction that tattooing was an art, Hardy opened the first appointment-only tattoo parlor in 1974, in San Francisco, where each customer received a unique commissioned design. It took a while to build up a clientele, but eventually people came around to the idea that there was more to body ink than anchor tattoos.

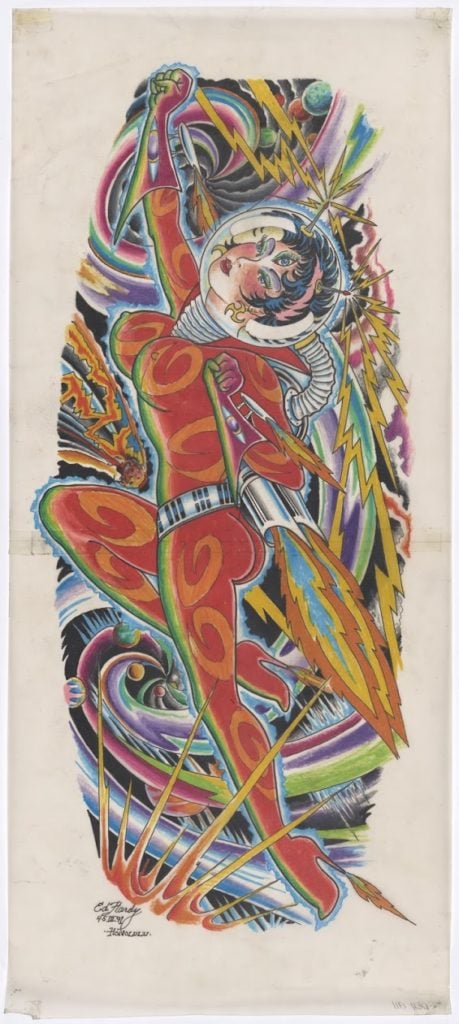

Don Ed Hardy, Future Plans (1967). Courtesy of Ed Hardy/Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Hardy is hopeful that his upcoming museum show will help expose the medium, and his contributions to the form, to an even broader audience. “In addition to the tens of thousands of tattoos I did over about 40 years, I always continued drawing, painting, and doing my personal art,” he added. “I think it will open a lot of eyes.”

We spoke to the artist about the show, his artistic background, and yes, the Ed Hardy brand that so many people love to hate.

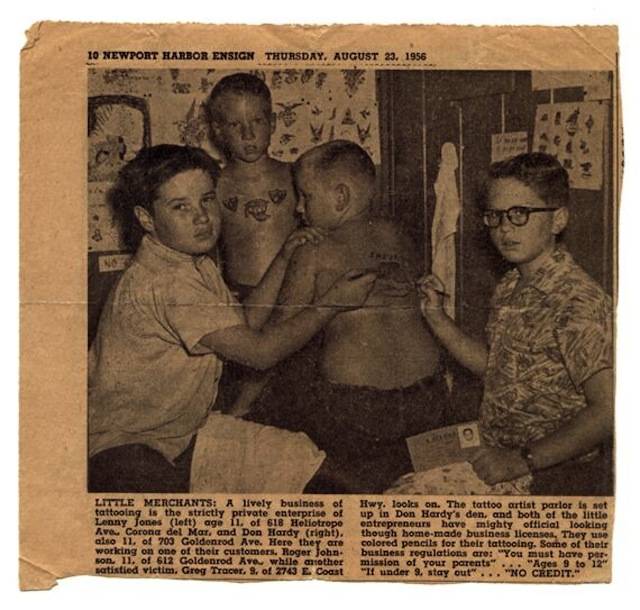

Ed Hardy’s childhood tattoo shop in the local paper, Newport Harbor Ensign (1956). Photo courtesy of Ed Hardy.

How did you develop an interest in tattooing?

My best friend’s dad had been in World War II. He had seven or eight small tattoos, typical designs. Then I began visiting tattoo shops about 20 miles up the coast from where I lived in Southern California.

A famous tattoo artist, Bert Grimm, let us hang out in his shop. I drew sketches from the designs on his walls, and drew them up as display sheets—flash, as it’s known in the tattoo business. Then I started a toy tattoo shop in my house where I would draw on neighborhood kids with Maybelline eyeliner and watercolor pencils.

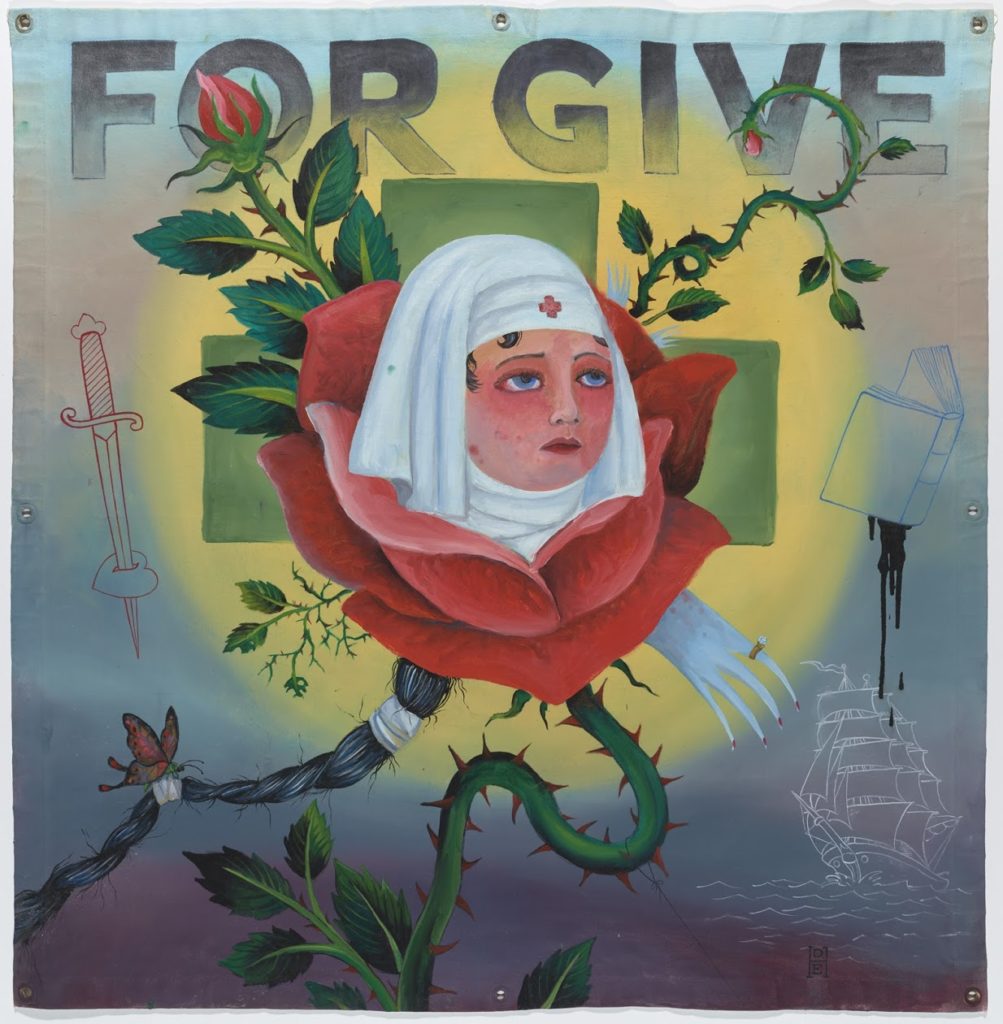

Don Ed Hardy, Forgive (1995). Courtesy of Ed Hardy/Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

After graduating college, how did you decide between pursuing a more traditional artistic path, having been offered a graduate teaching scholarship at Yale, and becoming a tattoo artist?

It was leap of faith. I graduated in 1967 and was lined up to go to Yale. But I reconnected with an old buddy at an art show and a bunch of us ended up going up to Oakland and getting tattoos at [the academic-turned-tattoo artist] Phil Sparrow’s shop.

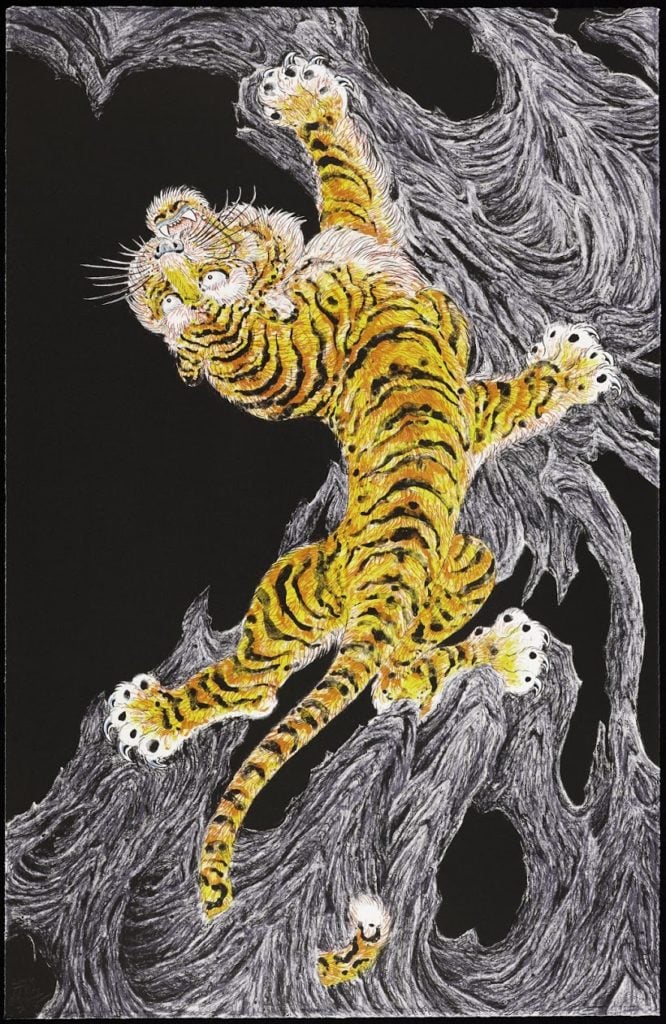

When Phil heard I was an art student, he showed me a book of classical Japanese tattooing [Irezumi: Japanese Tattooing, 1966]. I thought, if tattoos could be this magnificent and accomplished, I would like to do it. And I love that tattoos avoid commodification. I just made a huge turnaround and said, “I’m not going to go to graduate school; I think tattooing could be a fantastic career.”

Don Ed Hardy, Untitled (futuristic female astronaut) tattoo design for rib (1991). Courtesy of Ed Hardy.

Did success come easily?

It’s a very difficult medium because it’s permanent. There’s no eraser and there’s all the the psychological baggage and responsibility that comes from a person choosing to mark their skin.

That’s what made it fascinating to me, but I really struggled with it. Phil Sparrow helped me do tattoos under his supervision on some art-school buddies. I basically worked my way up to it with the artistic talent that I had, but it was a long, hard slog.

Don Ed Hardy, Climber (2011). Courtesy of Ed Hardy/Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

How did the Ed Hardy fashion line, with which your name is so closely associated, come about?

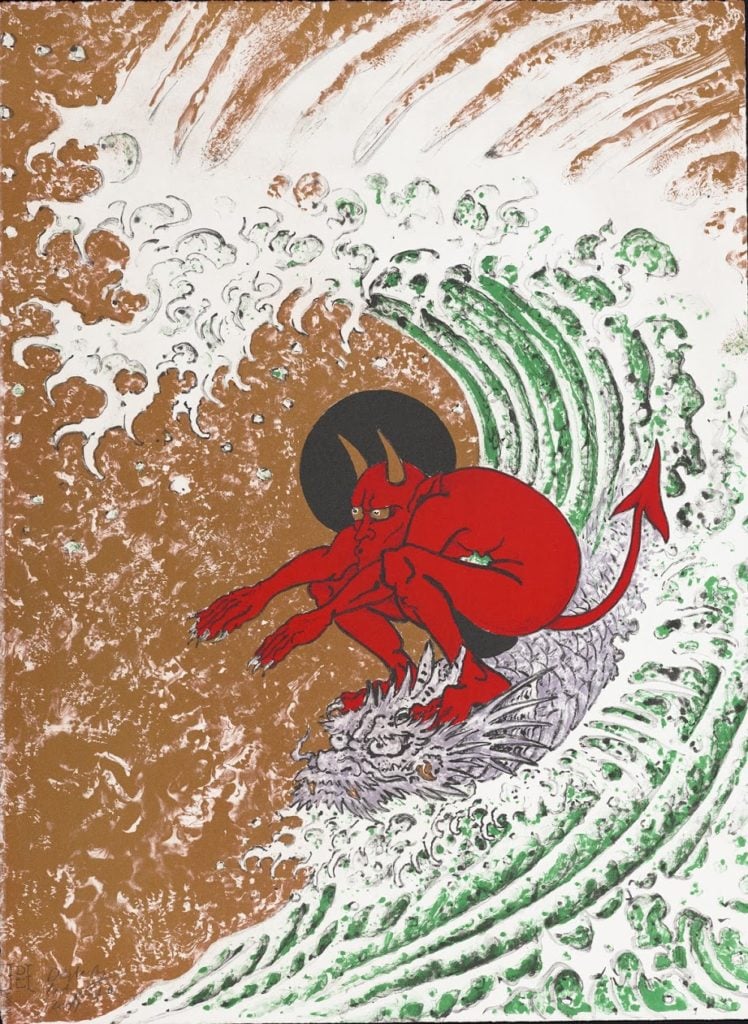

It was based on some of my classic tattoo flash from way back when. A company from Japan saw in an article about me and approached me about putting my artwork on clothing and turning it into a fashion thing. I wasn’t interested, but they persisted and we started the brand up.

They had a store in Los Angeles, and that caught the eye of Christian Audigier, who also did the Von Dutch clothing line, based on the famous car painter and pinstriper. He was completely connected to the Hollywood stars and the thing took off like a rocket.

Christian was one of those “any publicity is good publicity” people, and he didn’t care who was wearing the Ed Hardy brand. Some of them were not great, inspiring people in the pop culture world. I want to say one of them was this guy, Jon Gosselin? I was aware of about ten percent of what was happening. It was really surreal.

Did you ever get upset by the backlash against the Ed Hardy brand?

I didn’t take it personally! They didn’t like the preening clown who was wearing the stuff. I thought, “I’m not like that guy—I just drew the images!”

Don Ed Hardy, Surf or Die (2004). Courtesy of Ed Hardy.

Do you see donating your work to the Fine Arts Museums and holding your first museum retrospective as a way of securing an artistic legacy on your own terms, independent of the Ed Hardy brand?

Yes, I do. The Ed Hardy clothing line, that’s what everybody knows when they hear my name. They have no idea that there’s more behind it. I think the show will dramatically expose my work to people, so I was completely thrilled and honored to have the museum approach me.

What can we expect from the show?

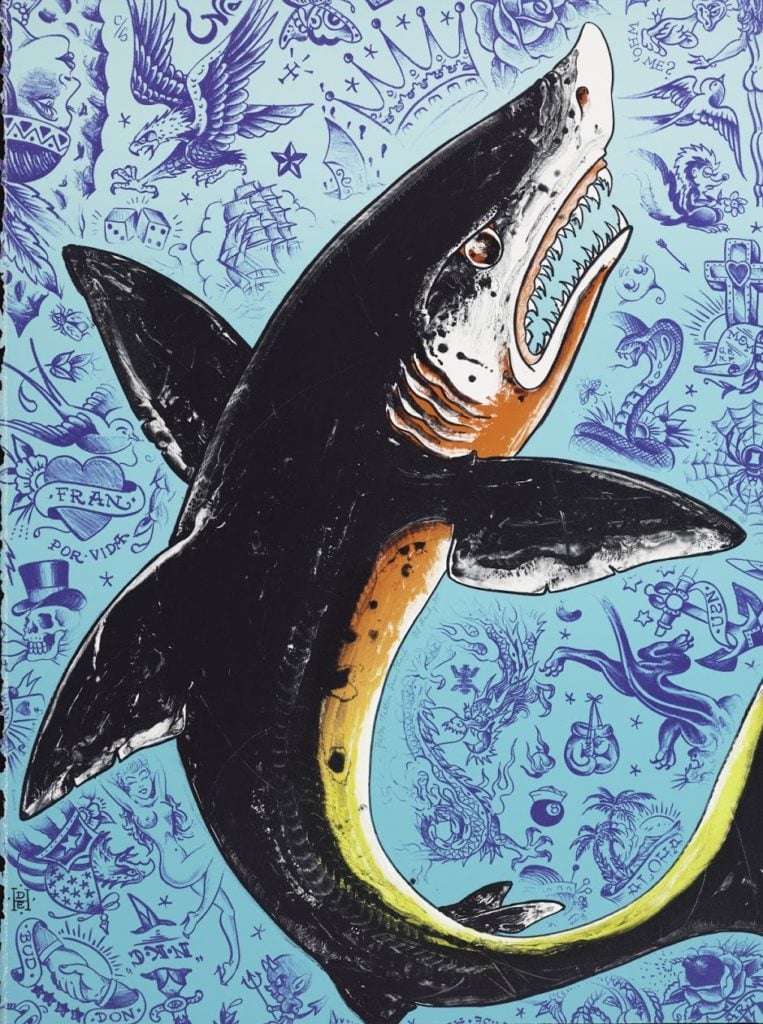

I’m very prolific and in addition to the tens of thousands of tattoos I did over about 40 years, I continued drawing, painting, and doing my personal art that was made with no intention of becoming a tattoo. There’s an enormous range.

Don Ed Hardy, Tattoo Seas Shark (1995). Courtesy of Ed Hardy/Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

I’m also donating this 2,000-square-foot dragon painting I did in the millennial year, which was the year of the dragon. It’s four feet tall and 500 feet long. It always gets a lot of attention when it’s shown. The inspiration is on one of the most famous dragon paintings in the world, Nine Dragons by Chen Rong at the Museum of Fine of Arts Boston.

In the mid-’60s when I was tattooing in San Diego, I saw a reproduction in a book. Years later, I made an appointment with the museum and they took the scroll out and I was able to spend an hour looking it over with magnifying glass. It totally knocked me out.

Don Ed Hardy, 2000 Dragons, detail. Courtesy of Ed Hardy.

You also helped out with “Pierced Hearts & True Love: A Century of Drawings for Tattoos” at the Drawing Center in 1995. How did you get involved?

My friend Michael McCabe, a great historian and writer who was a practicing tattoo artist, was great friends with Ann Philbin [the director of the Drawing Center at the time]. I contacted a number of people, most of them younger than myself, to put their work in the show. It was a tremendous success and a great honor.

Do you feel that tattooing should be more widely represented in museums?

Tattooing is one of the most exciting mediums on the planet. It’s the most ancient form—I think it probably predates the cave painting. It would be natural for people to put a mark on themselves with charcoal from the fire. It’s a very human activity that has been looked down on for so long because of the Judeo-Christian control system in the West. And there’s more spectacularly accomplished tattooing being done than ever, so it’s natural that it could be seen in a museum.

“Ed Hardy: Deeper Than Skin” will open at the de Young museum, Golden Gate Park, 50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive, San Francisco, California, in July 2019.